Mathew Dalgleish (University of Wolverhampton)

Abstract

Many people with a disability play games despite difficulties in relation to access or quality of experience. Better access is needed, but there has been limited industry interest. For players with motor impairments the focus has been on the controller. Numerous solutions have been developed by third parties, but all are likely unsuitable for at least some users and there remains space for radically alternative angles. Informed by my experiences as a disabled gamer, concepts of affordance and control dimensionality are used to discuss the accessibility implications of controller design from the Magnavox Odyssey to the present. Notions of incidental body-controller fit and precarious accessibility are outlined. I subsequently draw on Lévy’s theory of collective intelligence and example games Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes and Artemis Spaceship Bridge Commander to develop a model that uses asymmetrical roles and diverse input to fit individual abilities and thereby expand participation.

Keywords: disability, controllers, asymmetrical roles, motor impairment, control dimensionality.

Introduction

The barriers faced by people with disabilities are often considered in terms of two theoretical models: the medical model and the social model. The medical model of disability locates disability in the mind or body of the individual “patient” and emphasises linear restoration to “normality” (Gough, 2005). This was contested (UPIAS, 1976, pp. 3-4; Locker, 1983, p. 90) and there followed a shift to a social model of disability that posited that people are disabled by the attitudes of society (Shakespeare, 2016). If arguably outdated (Owens, 2014), the social model remains widely adopted.

Under the social model, suitably designed technologies are seen to enable people with disabilities to fulfil their desires to socialise, work, learn and play (Arrigo, 2005; Cobb et al., 2002; Hasselbring & Glaser, 2000); potentially improving independence (Jewell & Atkin, 2013) and quality of life (Arrigo, 2005). As video games have increased in popularity (Statista, 2017), there has been great interest in how video games might benefit players generally (Jackson et al., 2012; Posso, 2016) and people with disabilities specifically. For example, Jiménez, Pulina and Lanfranchi (2015) review how video games can improve the cognitive abilities of players with intellectual disabilities. Elsewhere, Rowland et al. (2016) study how active video games can help improve the fitness of players with lower-limb impairments. There are numerous other examples, but enjoyment remains the main motivation for many players.

The number of players with a disability is significant: there are 215 million players in the US alone and more than 32 million state that they have a disability (Statista, 2018; The Economist, 2017). While many players with disabilities find the types of games they can play limited (Flynn & Lange, 2010; Dolinar & Fels, 2014), there are many other people with disabilities who have been unable to participate at all (Flynn & Lange, 2010). Organisations such as AbleGamers and SpecialEffect strive to improve access, but resources are finite (SpecialEffect, n.d.).

With this background, this paper will now discuss some of the ways that disability and motor impairment specifically can impact participation, including relevant personal experience. Attention will be paid to the often-precarious nature of access given the rapid evolution of video game controllers. Existing work will be critically reviewed, and a new accessibility model developed around asymmetric roles and controllers. This addresses some of the limitations of existing solutions and provides plentiful possibilities for future work.

Impairment and the interaction loop

Disabilities and experiences of disability are inherently extremely diverse, but Bierre et al. (2005) propose that four broad types of impairment commonly impact video game players:

- Visual impairment

- Auditory impairment

- Motor impairment

- Cognitive impairment

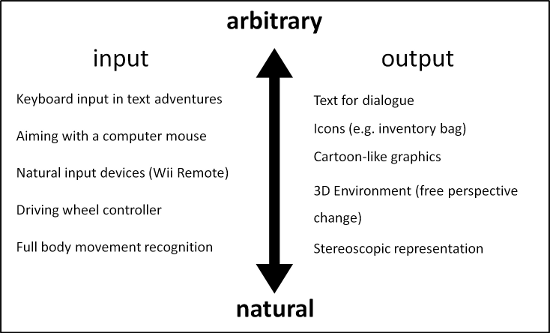

By contrast, Yuan, Folmer and Harris (2011) focus on the effects of impairment, stating that difficulties typically relate to:

- ability to receive feedback

- ability to determine in-game responses

- ability to provide input using conventional input devices

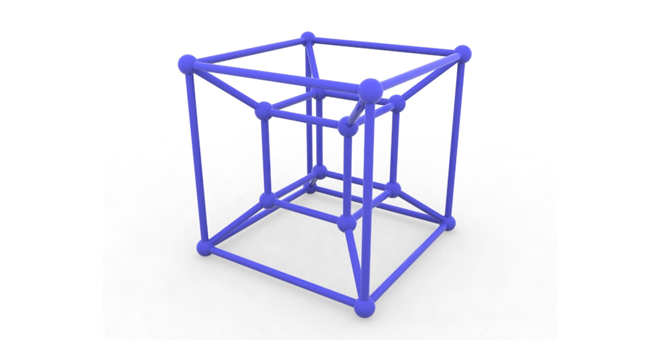

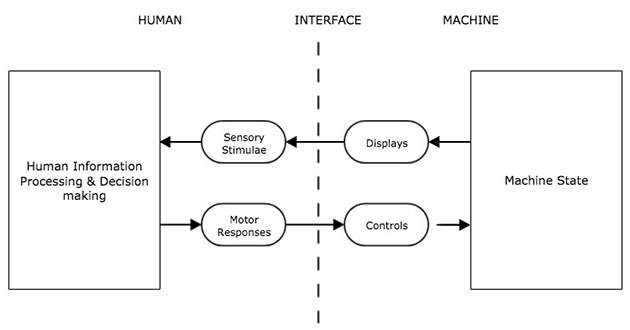

These can be positioned within a classic human-machine interaction loop (Fig. 1). In short, the user provides control input; the system processes the input and produces an output. This output is passed back to the user at the interface. The user perceives the system output, processes it, and provides further input (Bongers, 2000).

Figure 1. The human-machine interaction loop (Bongers, 2000).

For reasons that will shortly be apparent, this article will focus on motor impairment and restricted mobility, and the ability to provide input.

While traditional video games are considered sedentary (Lu et al., 2016), they make considerable demands of players in terms of eye-hand and bimanual coordination, dexterity of response and stamina in the hands. These demands meet the abilities of the player at the interface or, more specifically, at the controller. Players with motor impairments can be limited in the type or amount of input they can provide (Yuan, Folmer & Harris, 2011) and standard controllers can therefore be a particular barrier to participation.

Affordance and control dimensionality

Two concepts can help us to consider the interaction possibilities of video game controllers and the interaction demands made of players: affordance and control dimensionality (CD). Donald Norman (1988, p. 9) used the term affordance to refer to the actions made possible by an object’s physical form and properties. However, the intangible properties of software limited its tenability and the concept was revised to emphasise a distinction between “real” and “perceived” affordances: actions that are actually possible and actions that users perceive to be possible (Norman, 1999).

A more recent concept and specific to a video game context, CD is a measure of the degree of complexity inherent in a system as a result of its interaction demands and possibilities (Mustaquim & Nyström, 2014). There are two steps (Swain, 2008, pp. 135-138), the first being to assess the primary movement scheme:

- One dimension of movement (left-right) CD = 1

- Two dimensions of movement (left-right, up-down) CD = 2

- Three dimensions of movement (left-right, up-down, in-out) CD = 3

A second step adds additional CDs for each secondary dimension of control:

- For each additional movement dimension: strafe back-forth, accelerate-brake, rewind or fast-forward time, etc. (typically use two buttons) = 1

- For each embedded action: jump, attack, rotate, etc (typically use one button) = 0.5

In isolation, controllers do not have any inherent CD as this is co-dependent on the particular game design, but they do have a (maximum) potential CD.

Evolution of the controller

As the affordances (i.e. action possibilities) of controllers have generally increased, so too have their complexity and interaction demands. To this end, the table below (Table 1) shows how the potential CD of a representative selection of controllers has evolved over time.

| Name | Year | Directional Control Type | Dimensions of Movement | Buttons | Total CD |

| Magnavox Odyssey | 1972 | Two Knobs | 2 x 1 | 0 | 2 |

| Atari Computer System | 1977 | Joystick | 2 | 1 | 2.5 |

| Nintendo Entertainment System | 1983 | D-pad | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Sega Master System | 1985 | D-pad | 2 | 2 | 3 |

| Sega Mega Drive | 1989 | D-Pad | 2 | 4 | 4 |

| Super Nintendo Entertainment System | 1990 | D-Pad | 2 | 6 | 5 |

| Sony PlayStation (initial controller) | 1994 | D-Pad | 2 | 10 | 7 |

| Nintendo 64 1 | 1996 | Analogue thumbstick | 2 | 14 | 9 |

| Sony PlayStation DualShock controller | 1997 | Dual analogue thumbsticks | 2 x 2 | 17 | 12.5 |

| Microsoft Xbox | 2001 | Dual analogue thumbsticks | 2 x 2 | 16 | 12 |

| Nintendo Wii Remote and Nunchuck | 2006 | One analogue thumbstick and one 3-D accelerometer per controller | (2 x 2) + (2 x 3) | 13 | 16.5 |

| Microsoft Kinect | 2009 | Various | Various | Various | – |

| Sony PlayStation 4 | 2013 | Dual analogue thumbsticks | 2 x 2 | 17 | 12.5 |

| Nintendo Switch Pro Controller | 2017 | Dual analogue thumbsticks | 2 x 2 | 14 | 11 |

| Nintendo Switch Joy Con | 2017 | One analogue thumbstick and one 3-D accelerometer per side | (2 x 2) + (2 x 3) | 14 | 17 |

Table 1: CD of a Representative Selection of Video Game Controllers (1972-2017)

At this point it is pertinent to note that some kinds of interface resist classification. Firstly, the potential CDs of interfaces such as the Microsoft Kinect and integrated multitouch interface/platforms such as smartphones and tablets are highly variable and primarily defined by how they are used in the context of individual games: the player can be presented with simple, one-button gameplay or more complex, multi-dimensional interaction. Second, some interfaces feature secondary sensors. For instance, the Kinect features a microphone array, while smartphones and tablets typically contain a microphone, plus a 3-D accelerometer and/or gyroscope. These can be used to replace or supplement more conventional controls but are employed in selected games only. Thirdly, there are new types of interface whose affordances are not yet well understood. For instance, brain-computer interfaces (BCIs) are only starting to edge into the mainstream (Ahn, Lee, Choi & Jun, 2014).

Nevertheless, particularly relevant to players with motor impairments is the broad correlation between increased potential CD and increased action possibilities, and heavier interaction demands. Not all games use all of the potential CD, but newfound action possibilities are typically soon exploited by game designers; at the cost of increased interaction demands and complexity.

The first controllers were very simple (low CD). The Magnavox Odyssey controller (CD = 2) had one knob for vertical movement and a second for horizontal movement. There were no buttons. The included titles Table Tennis and Ski used only the vertical knob and horizontal knob respectively. These limited affordances resulted in modest interaction demands: ideal for a population only recently introduced to video games.

The Atari Computer System joystick (CD = 2.5) allowed movement in four directions and featured one action button only, but comparatively more sophisticated affordances evolved. For instance, Asteroids enabled the player ship to independently rotate left or right, thrust forward and fire. However, these action possibilities meant that players also needed to coordinate more than one simultaneous action.

The Nintendo Entertainment System controller (CD = 4) replaced the joystick with a four-way directional pad (D-Pad). It also featured two action buttons and two secondary buttons (Diskin, 2004). The D-pad required smaller movements than the Atari joystick and so games designers could demand players provide more nimble and precise input. Additional buttons afforded more varied player actions; at the cost of increased interaction complexity. For example, Punch-Out!! made use of the A and B buttons plus D-pad to punch left and right, but also the Start button to throw an uppercut (u.a., 2017). Similarly, Double Dragon II: The Revenge used a two-button combination to deliver a jump kick (Nintendo, 1990).

A decade on, the small analogue joysticks of the Nintendo 64 (CD = 9) and Sony DualShock (CD = 12.5) controllers had relegated the D-pad to secondary functions only. The twin joysticks of the DualShock (Plunkett, 2011) fell neatly under the thumbs and enabled movement and viewpoint to be decoupled. Running in one direction while aiming in another has become a canonical feature of first-person shooter titles (McMahan, Bowman, Zielinski and Brady, 2012), but poses a significant increase in interaction complexity: the player must not only coordinate two simultaneously 2-D inputs, but also provide input that is proportional and precise, at the same time as operating multiple buttons.

Incidental fit and the precariousness of access

If increased CD can produce (or be the result of) extended affordance, an inadvertent consequence of resultantly increased interaction demands is that players with motor impairments like Microsoft employee Solomon Romney can be abruptly excluded. Born without fingers on his left hand, Romney readily adapted to the simple controls of 1980s arcade machines (Stuart, 2018) and played for over a decade. However, the expanded affordances of the PlayStation controller eventually led to unmeetable demands related to extensive use of “chaining” together sequences of button combinations (Stuart, 2018).

My own experiences are similar. Born with transverse hemimelia and bilateral fibular hemimelia, I have no left arm below the elbow except for a thumb-like protuberance on the elbow, and extensive lower limb deformity. Despite this unpromising physicality, I received a NES for my fifth birthday. With no predetermined concept of how to play, I intuitively rested the controller on the floor, then used my left foot to manipulate the D-pad and right hand to operate the buttons. I had no sense that this was unusual.

Over time I moved from the NES to the SNES, to the Sega Dreamcast and finally on to PlayStations 1 to 4. The evolution of the controller prompted my interactions to slowly develop into the comparatively more conventional style I use today (Fig. 2). The flexibility and open-endedness of these interfaces arguably facilitated this serendipitous fit: the controller did not prescribe exactly how it must be used but could instead (inadvertently) support varied bodily affordances and interaction styles.

Figure 2. The current interaction style of the author: left thumb at elbow joint operates left analogue stick and D-Pad, right hand operates right analogue stick and all buttons.

If such instances of incidental fit between unconventional bodily affordances and standard controllers are rarely mentioned in a video game context, there are antecedents elsewhere, notably in music; another domain that requires complex real-time control. Examples include pianist Paul Wittgenstein and guitarist Django Reinhardt (Dalgleish, 2014).

There is nonetheless a fundamental difference between the two domains: traditional musical instruments have evolved extremely slowly (Fletcher & Rossing, 1991: v-vi), but video games and their controllers have evolved very rapidly (Bhardwaj, 2017): relatively suddenly, players can find interaction demands unmeetable. Like Romney (Stuart, 2018), my own exclusion came unexpectedly. It related to the shift from handheld to gestural controllers. The innovative Wii remote was unproblematic in itself; the problem lay in that most games required concurrent use of a Nunchuck (second controller). While more conventional controllers can be held – if not necessarily operated – by one hand, this combination assumed that the player could both hold and operate one controller in each hand: a seemingly inconsequential difference that essentially precluded my participation.

The success of the Wii inspired related approaches. Most notably, Microsoft developed the Kinect; a camera and infrared-based motion controller for the Xbox 360 that promised whole body interaction without a physical controller (Zhang, 2012). However, it soon became apparent that the Kinect could not map its skeleton model onto my body: I had to return to using a more conventional controller only. The irony is that Nintendo and Microsoft intended these systems to broaden participation (Ulicsak, Wright & Crammer, 2009; Chen, Li, Ngo & Sun, 2011). Instead, their narrow and inflexible schemes of allowable interactions effectively disempowered one subset of possible users in order to empower another.

Related work: adapted controllers and new designs

Examples similar to the above have rarely been considered in prior literature. Instead, efforts to increase the accessibility of video games for players with motor impairments have tended to focus on three aspects:

- Remapping of controls in software

- Hardware modifications to standard controllers

- Development of new/alternative controllers

Remapping refers to the ability of software to flexibly redistribute controls in order to suit particular player abilities and preferences. Game Accessibility Guidelines state that: “Many people […] benefit greatly from being able to move essential controls into positions that they are able to reach more easily” (Game Accessibility, u.d.). For instance, professional Street Fighter player BrolyLegs (Street Fighter, 2016) remaps controls in order to play using his face. If the ability to remap controls is implemented, a range of different mappings can be quickly tested, at little or no cost. However, remapping alone may be insufficient for some needs and is rarely implemented on consoles (Game Accessibility, u.d.).

Modifications to standard controllers have been aided by the spread of Maker culture. They vary considerably in their complexity. At one end of a continuum are modest changes to controls to make them easier to grip or press. For instance, Caleb Kraft has presented a relatively simple, modular design for 3-D printed joystick that can broadly increase controller accessibility (Kraft, 2015a), as well as modified thumbstick buttons for a player with muscular dystrophy (Kraft, 2014). Other modifications are more complex. For example, the Single Handed Gaming Controllers for Accessibility Use project by Ben Heck (u.d.) extensively modifies standard controllers to enable one-handed operation.

While modifications to standard controllers can be useful for some players they have some limitations. For instance, they can be difficult to produce in larger numbers. As Caleb Kraft (2015b) comments: “The biggest issue that I run into is time. I simply can’t keep up with the requests.” Another issue for adapted controllers is that they can be difficult to sell as they are usually informal (and relatively untested) modifications of a commercial device (Iacopetti, Fanucci, Roncella, Giusti & Scebba, 2008).

With the Nintendo Hands Free controller for the NES a rare exception (Plunkett, 2009), the main manufacturers have shown limited interest in accessible controllers. Instead, new, accessibility-focussed controller designs have typically come from third parties. Quadstick (u.d.) have produced three controllers aimed at quadriplegic players and featuring combinations of spatial, pressure and “sip/puff” sensors, and head-operated joysticks. At the other end of the body, Gyorgy Levay and team developed the Game Enhancing Augmented Reality controller; a padded device operated by the feet (Cragg, 2016).

More flexible, modular approaches have been proposed by Iacopetti et al. (2008) and, most recently, Microsoft. The Microsoft Adaptive Controller is informed by its earlier Xbox Elite controller: a professional esports controller adopted by some players with limited mobility (Stark & Sarkar, 2018). The Adaptive Controller is not aimed at a specific disability but provides a flexible hub for additional input devices (Microsoft, 2018; Englard, 2018). Released in late 2018, its customisability has the potential to meet the needs of disparate players, without the sometimes-prohibitive costs of bespoke production.

Entirely new classes of controls continue to emerge, and some have been applied to a video game accessibility context. For instance, Brain-Computer Interfaces (BCI) emerged in the early 1970s (Vidal, 1973), but more refined, widely available and lower cost designs have appeared only in the last decade. As BCIs – primarily using electroencephalographic signals – have become more readily available, they have been used as video game controllers (Ahn, Lee, Choi & Jun, 2014). Researchers have also started to explore the potential of BCIs for disabled gamers (Maby et al., 2012), but they remain nascent and beyond further coverage in this paper.

Asymmetrical roles and asymmetrical controllers

This article has identified numerous ideas and developments around controllers and accessibility. All are likely imperfect to at least some people and universal accessibility is probably unachievable (Barlet & Spohn, 2012; Vanderheiden & Henry, 2003). As such, alongside additional considerations such as cost, the need for setup help and hard-to-predict individual preferences, it is surely fruitful to continue to explore multiple directions.

While attempts to make games more accessible to players with motor impairments have focussed on controllers and mappings, game mechanics have also been considered. For example, Barlet and Spohn (2012) discuss the power of adaptive difficulty. More generally, the social mechanics of multiplayer games have been deliberated (Quandt & Kröger, 2013; Siitonen, 2007), but standard controllers are usually assumed. There also remains scant consideration of how multiplayer experiences can inform controller design; or how they might inform the interface for motor impaired players.

A rare exception is a user-selectable Xbox One feature called Copilot. This links two controllers so that they can be used as one, in order to provide assistance as needed (Englard, 2018). The Copilot model can be criticised on at least three grounds. First, the pilot-co-pilot relationship has an inbuilt power dynamic; the pilot player is beholden to a “better” player for help. Second, all other aspects of the game remain identical to the single player version: the potentials of multiple players are not explored. Third, social isolation is an issue for many people with disabilities (Scope, 2017), but Copilot allows for cooperation in-person only; it does not exploit the social potentials of the internet.

A less restrictive basis is provided by Pierre Lévy (1997, p.13) and the notion of collective intelligence: “a form of universally distributed intelligence, constantly enhanced, coordinated in real time, and resulting in the effective mobilization of skills.” Proposed at a more utopian time for the internet, collective intelligence posits a shift from human-machine interaction to collaborative human-human interactions. Particularly relevant for its implicit embrace of diversity is the assertion that: “No one knows everything, everyone knows something, all knowledge resides in humanity” (Lévy, 1997, p.13); a notion reinforced by the statement: “Before we can mobilize skills, we have to identify them. And to do so, we have to recognize them in all their diversity” (Lévy, 1997, p.13).

Lévy (1997) already intends “intelligence” to refer to a duality; not only the construction of ideas but also the construction of people (i.e. society) (p. 10). Perhaps it can be extended further still, to account for how brain-centric views of cognition have been increasingly challenged by embodiment: the notion that the body is needed for intelligence (Pfeifer & Bongard, 2007, xvii). Related, Paul Dourish (2001) has proposed embodiment as a foundation for human-machine interaction. If this shift can be accepted, it is possible to reframe Lévy’s statement to conceive a model of interaction whereby no-one can do everything, but everyone can do something.

An example of this kind of asymmetric collaborative play in a musical context is Harmony Space: a multi-user system created by Simon Holland (1993) that enables collaborative roles to be split in numerous ways. For instance, non-traditional roles such as steering the root note, changes to key, chord size and inversions, can be distributed across one or more players. Many pieces of music require only two or three roles, but interplay can still deliver rich sequences. A more recent version of Harmony Space (Bouwer, Holland & Dalgleish, 2013) also expands the variety of controller types that can be used, from dance mats to MIDI foot pedals. This added flexibility enables players to choose the most appropriate controller for their selected role and abilities.

There are also examples of video games that make use of asymmetrical roles. For instance, Gandolfi (2018) explores how players use asymmetrical roles to develop cooperative and computational thinking in the online multiplayer games Overwatch, For Honor and Tom Clancy’s Rainbow Six: Siege. However, these are not aimed at players with a disability and the expectation is for all players to use a similar controller.

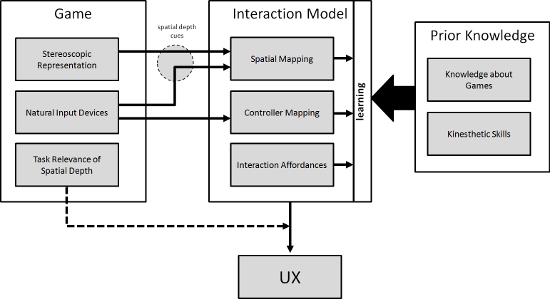

More useful in an accessibility context are Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes (KTNE) and Artemis Spaceship Bridge Commander (ASBC). KTNE features one player as the Defuser and one or more other players as Experts. The Defuser must diffuse a bomb before time runs out but must be guided by the Experts. The Experts have access to the instructions but cannot see or interact with the bomb directly. Controller options for the Defuser include keyboard and mouse, touchscreen and gamepads, and the Experts and Defuser communicate verbally, in person or online. A number of design decisions help to increase the game’s accessibility. First, players are able to select from two roles that are equally vital but highly asymmetric in their interaction demands. Second, the Defuser role supports several different input devices, and these may further increase the diversity of compatible bodily affordances. Third, a “free play” mode enables the countdown timer to be adjusted; useful if a player requires extended time to provide input.

ASBC requires multiple (ideally six) players, and at least one Microsoft Windows computer. The six available roles are highly asymmetric in the skills and abilities they require for players to succeed (Justin, 2013). While the Captain must use a Windows machine, mobile devices can be used for the other roles if desired. Regardless of the devices used, inter-player voice communication is the primary way to coordinate complex ship operations.

A strength of both titles is that while roles are highly asymmetrical, fundamental principles such as reward, goals, challenge and meaningful play (Barrett, Swain, Gatzidis & Mecheraoui, 2016) are maintained. While ASBC is more restrictive in some respects than KTNE, its more extensive roles also allow for more extended differentiation in role requirements and interaction demands. That all but the player in the Captain role can choose from mobile, laptop or desktop platforms enables players to use a wide variety of devices and to customise interaction to suit individual requirements.

The “asymmetrical roles and asymmetrical controllers” (ARAC) model exhibited by KTNE and ASBC is still to be formally tested in the context of games and disability. Indeed, there are few if any documented cases of informal use. Nevertheless, the asymmetrical roles and asymmetrical controllers can be seen to oppose the notion of “parallel game universes” developed by Grammenos, Savidis and Stephanidis (2009). This aims to create subspaces of differential difficulty in order for both players with and without impairments to play cooperatively or against each other in a way that provides equivalency of difficulty (Grammenos et al., 2009). However, in order to achieve a balance, the player with impairments is provided with a simplified and arguably lesser version of the “full” experience.

Rather than segregate players with disabilities by placing them in exclusive sub-sections that provide “cut-down” versions of the canonical experience in an attempt to manage challenge and difficulty, the ARAC model has all players – impaired or otherwise – play in the same space. Players also all engage in the same tasks (there are no simplified iterations) but do so from different perspectives. More specifically, players can adopt different roles and input modalities that best suit their individual abilities. For instance, players with motor impairments might use voice input to direct the actions of other players or use physical input devices in non-real-time (i.e. less temporally-critical) roles.

Conclusions and future work

This paper has outlined the evolving nature of developments around video games and accessibility, highlighted some current limitations, and outlined the ARAC model as a potential solution to some of these issues. A particular problem for any accessibility model is a persistent lack of adoption, seemingly as a result of apathy on the part of industry. This apathy is likely at least partly financially motivated in that, despite the apparent size of the market, prior developments have tended to be one-offs: bespoke adaptations or entirely bespoke designs for individual players. These are usually relatively costly and require specialised expertise to develop but have few of the economies of large-scale production and limited mainstream potential. The ARAC model has promise in this respect: rather than craft one-off controllers to adapt titles that would ordinarily be inaccessible, ARAC improves accessibility by making diversity of roles and input a fundamental tenet of game design.

From an accessibility perspective, it is important that a wide variety of input devices are supported so that players can try out and mix-and-match different combinations until individually optimised solutions are found. Moreover, asymmetrical roles inherently imply the use of a range of input devices: different roles have different affordances and interaction demands, that in turn imply particular types of input. Although controllers are often treated as generically interchangeable, KTNE already demonstrates how matching of game mechanics and input modalities can produce gameplay that is original and accessible.

It is important to note that this does not necessarily mean simple or simplistic gameplay. Although, as in Harmony Space (Holland, 1993), individual roles may have modest interaction demands (i.e. low CD), heterogeneous but well-coordinated combinations of players can adeptly complete very complex tasks: as is also the case with complex problems in the real-world (Kirschner, Paas, Kirschner and Janssen (2011)).

If roles can already be seen to suggest some types of controller over others, matches between controllers and unconventional bodily affordances remain poorly understood. For instance, if simpler (low CD) controllers can allow for more flexibility of use and may therefore accommodate diverse users, it is not yet clear how to predict matches between bodies and controllers new or old, bespoke or mass-produced. Thus, trial and error remain a necessity for most motor impaired players and disabled players more broadly. As such, there is still much to be done. Pertinent future directions include:

- Identification of additional games that have the potential to be case studies, and to study their player-game relationships longitudinally and preferably in-the-wild so that issues can be understood in situ.

- Exploration of particular aspects within the broader ARAC model to enable more certainty in implementation and leading to guidelines for game designers and the design of new games. For instance:

- development of a framework for assessing the likely fit between (old and new) controllers and diverse user needs;

- examination of how to best match player roles to a variety of interfaces.

- Development of interfaces that reflect how the effects of disability can change over time (even day to day) and adjust their response accordingly (i.e. adaptive interfaces).

- Education of games industry staff, particularly those with strategic responsibilities, in order to increase awareness of accessibility issues. This may be crucial if accessibility is to be “designed in” to games from the outset of their development.

References

Ahn, M., Lee, M., Choi, J. & Jun, S.C. (2014). A review of brain-computer interface games and an opinion survey from researchers, developers and users. Sensors, 14(8), pp. 14601-14633.

Arrigo, M. (2005). E-learning accessibility for blind students. In Proceedings of the 3rd International Conference on Multimedia and ICTs in Education – m-ICTE2005.

Barlet, M.C. & Spohn, S.D. (2012). Includification: a practical guide to game accessibility. Retrieved from https://www.includification.com/AbleGamers_Includification.pdf

Barrett, N., Swain, I., Gatzidis, C., & Mecheraoui, C. (2016). The use and effect of video game design theory in the creation of game-based systems for upper limb stroke rehabilitation. Journal of Rehabilitation and Assistive Technologies Engineering, 3, pp. 1-16.

Bhardwaj, R. (2017). The ergonomic development of video game controllers. Journal of Ergonomics, 7(209).

Bierre, K., Chetwynd, J., Ellis, B., Hinn, D.M., Ludi, S. and Westin, T. (2005). Game not over: accessibility issues in video games. In Proceedings of the 11th International Conference on Human-Computer Interaction.

Bongers, B. (2000). Physical interfaces in the electronic arts: interaction theory and interfacing techniques for real-time performance. In M. Wanderley & M. Battier (Eds.), Trends in Gestural Control of Music. Paris, France: IRCAM.

Bouwer, A., Holland, S. and Dalgleish, M. (2013). Song Walker Harmony Space: embodied interaction design for complex musical skills. In: S. Holland, K. Wilkie, P. Mulholland, & A. Seago (Eds.), Music and Human-Computer Interaction (pp. 207-221). London, UK: Springer.

Chen, C., Li, G., Ngo, P., & Sun, C. (2011). Motion sensing technology. Management of Technology, e103(2011).

Cobb, S., Beardon, L., Eastgate, R., Glover, T., Kerr, S., Neale, H. (…) Wilson, J. (2002). Applied virtual environments to support learning of social interaction skills in users with Asperger’s syndrome. Digital Creativity, 13(1), pp. 11-22.

Cragg, O. (2016). ‘Handi-capable’ video game controller lets disabled gamers play without hands. International Business Times, 24th June 2016. Retrieved from https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/handi-capable-video-game-controller-lets-disabled-gamers-play-without-hands-1567256

Dalgleish, M. (2014). Reconsidering process: bringing thoughtfulness to the design of digital musical instruments for disabled users. In Proceedings of INTER-FACE: International Conference on Live Interfaces.

Diskin, P. (2004). Nintendo Entertainment System documentation. Retrieved from http://nesdev.com/NESDoc.pdf

Dolinar, G. & Fels, D.I. (2014). Mobility games ideation. In Proceedings of the 2014 University of Guelph Accessibility Conference.

Dourish, P. (2001). Where the action is: the foundations of embodied interaction. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Englard, K. (2018). Microsoft has created the most accessible gaming controller ever made. Retrieved from https://motherboard.vice.com/en_us/article/d3kvx7/microsoft-adaptive-controller

Fletcher, N.H. & Rossing, T. D. (1991). The physics of musical instruments. New York, NY: Springer.

Flynn, S.M. & Lange, B.M. (2010). Games for rehabilitation, the voice of players. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference on Disability, Virtual Reality & Associated Technologies.

Game Accessibility (u.d.). Game accessibility guidelines. Retrieved from http://gameaccessibilityguidelines.com/allow-controls-to-be-remapped-reconfigured/

Gandolfi, E. (2018). You have got a (different) friend in me: asymmetrical roles in gaming as potential ambassadors of computational and cooperative thinking. E-Learning and Digital Media, 15(3), pp. 128-145.

Gough, A. (2005). Body/Mine: a chaos narrative of cyborg subjectivities and liminal experiences. Women’s Studies, 34(3/4), pp. 249-64.

Grammenos, D., Savidis, A., & Stephanidis, C. (2009). Designing universally accessible games. ACM Computer Entertainment, 7(1).

Hasselbring, T. S. & Glaser, C. H. (2000). Use of computer technology to help students with special needs. Children and Computer Technology, 10(2), pp. 102-122.

Heck, B. (u.d.). Single handed Xbox One controllers. Retrieved from https://www.benheck.com/controllers

Holland, S. (1993). Learning about harmony with Harmony Space: an overview. In M. Smith, A. Smaill, & G. Wiggins (Eds.), Proceedings of a Workshop held as part of AI-ED 93, World Conference on Artificial Intelligence in Education, Edinburgh, Scotland, 25 August 1993 (pp. 24-40). London, UK: Springer.

Iacopetti, F., Fanucci, L., Roncella, R., Giusti, D., & Scebba, A. (2008). Game console controller interface for people with disability. In Proceedings of Second International Conference on Complex, Intelligent and Software Intensive Systems (CISIS-2008).

Jackson, L.A., Witt, E.A., Games, A.I, Fitzgerald, H.E., von Eye, A., & Zhao, Y. (2012). Information technology use and creativity: findings from the Children and Technology project. Computers in Human Behavior, 28(2), pp. 370-376.

Jewell, S. & Atkin, R. (2013). Enabling technology report. London, UK: Royal College of Art.

Jiménez, M.R., Pulina, F., & Lanfranchi, S. (2015). Video games and intellectual disabilities: a literature review. Life Span and Disability, 18(2), pp. 147-165.

Justin (2013). Beginner’s guide to Artemis: Spaceship Bridge Simulator. Retrieved from https://steamcommunity.com/sharedfiles/filedetails/?id=180128089

Kirschner, F., Paas, F., Kirschner, P., & Janssen, J. (2011). Differential effects of problem-solving demands on individual and collaborative learning outcomes. Learning and Instruction, 21(4), pp. 587-599.

Kraft, C. (2014). Modifying an Xbox One controller thumbsticks for muscular dystrophy. Retrieved from https://makezine.com/projects/modifying-an-xbox-one-controller-thumbsticks-for-muscular-dystrophy

Kraft, C. (2015a). Level up: these 3D printed thumbsticks help the disabled play Xbox. Retrieved from https://makezine.com/2015/01/30/level-up-these-3d-printed-thumbsticks-help-the-disabled-play-xbox/

Kraft, C. (2015b). Modifying Xbox controllers for gamers with disabilities: Ben Heck shows how. Retrieved from https://makezine.com/2015/12/14/modifying-xbox-controllers-for-gamers-with-disabilities-ben-heck-shows-how/

Lévy, P. (1997). Collective intelligence: mankind’s emerging world in cyberspace. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Locker, D. (1983). Disability and disadvantage. London, UK: Tavistock.

Lu, A.S., Baranowski, T., Hong, S.L., Buday, R., Thompson, D., Beltran, A., & Chen, T.A. (2016). The narrative impact of active video games on physical activity among children: a feasibility study. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 18(10).

Maby, E., Perrin, M., Bertrand, O., Sanchez, G. & Mattout, J. (2012). BCI could make old two-player games even more fun: a proof of concept with “Connect Four”. Advances in Human-Computer Interaction, 2012, pp. 1-8.

McMahan, R.P., Bowman, D. A., Zielinski, D.J., & Brady, R.B. (2012). Evaluating display fidelity and interaction fidelity in a virtual reality game. IIEEE Transactions on Visualization & Computer Graphics, 18(4), pp. 626-633.

Microsoft (2018). Xbox Adaptive Controller. Retrieved from https://www.microsoft.com/en-gb/p/xbox-adaptive-controller/8nsdbhz1n3d8

Mustaquim, M. & Nyström, T. (2014). Video game control dimensionality analysis. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Interactive Entertainment (IE2014).

Nintendo (1990). Double Dragon II game pak instructions. Retrieved from https://www.nintendo.co.jp/clv/manuals/en/pdf/CLV-P-NACHE.pdf

Norman, D.A. (1988). The psychology of everyday things. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Norman, D.A. (1999). Affordance, conventions, and design. Interactions, 6(3), pp. 38-43.

Owens, J. (2015). Exploring the critiques of the social model of disability: the transformative possibility of Arendt’s notion of power. Sociology of Health & Illness, 37(3), pp. 385-403.

Pfeifer, R. & Bongard, J. (2007). How the body shapes the way we think. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Plunkett, L. (2009). The disabled-friendly NES controller from the 1980s. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/5241760/the-disabled-friendly-nes-controller-from-the-1980s

Plunkett, L. (2011). The evolution of the PlayStation control pad. Retrieved from https://kotaku.com/5816069/the-evolution-of-the-playstation-control-pad/

Posso, A. (2016). Internet usage and educational outcomes among 15-year-old Australian students. International Journal of Communication, 10(2016), pp 3851-3876.

Quadstick (u.d.). Quadstick: a game controller for quadriplegics. Retrieved from http://www.quadstick.com/contact/

Quandt, T. & Kröger, S. (2013). Multiplayer: the social aspects of digital gaming. London, UK: Routledge.

Rowland, J.L., Malone, L.A., Fidopiastis, C.M., Padalabalanarayanan, S., Thirumalai, M., & Rimmer, J.H. (2016) Perspectives on active video gaming as a new frontier in accessible physical activity for youth with physical disabilities. Physical Therapy, 96(4), pp. 521-532.

Scope (2017). Nearly half of disabled people chronically lonely. Retrieved from https://www.scope.org.uk/press-releases/nearly-half-of-disabled-people-chronically-lonely

Shakespeare, T. (2016). The social model of disability. In L. J. Davis (Ed.), The disability studies reader (pp. 266-273). New York, NY: Routledge.

Siitonen, M. (2007). Social interaction in online multiplayer communities (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of Jyväskylä, Finland.

SpecialEffect (n.d.). Can we help? Retrieved from https://www.specialeffect.org.uk/can-we-help

Stark, C. & Sarkar, S. (2018). Microsoft’s new Xbox controller is designed entirely for players with disabilities. Retrieved from https://www.polygon.com/2018/5/17/17363528/xbox-adaptive-controller-disability-accessible

Statista (2017). Number of active video gamers worldwide from 2014 to 2021 (in millions). Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/748044/number-video-gamers-world/

Statista (2018). Penetration rate of gamers among the general population in the United States from 2013 to 2018. Retrieved from https://www.statista.com/statistics/748835/us-gamers-penetration-rate/

Stuart, K. (2018). How gamers with disabilities shaped the Microsoft Adaptive Controller. Retrieved from https://www.eurogamer.net/articles/2018-05-20-how-gamers-with-disabilities-shaped-the-microsoft-adaptive-controller

Swain, C. (2008). Master metrics: the science behind the art of game design. In K. Isbister & N. Schaffer (Eds.), Game usability: advancing the player experience (pp. 119-140). Burlington, MA: Morgan Kaufmann.

The Economist (2017). Games for people with disabilities. The Economist, 30 September 2017. Retrieved from https://www.economist.com/science-and-technology/2017/09/30/games-for-people-with-disabilities

u.a. (2017). Mike Tyson’s Punch-Out!!/getting started. Retrieved from https://strategywiki.org/wiki/Mike_Tyson%27s_Punch-Out!!/Getting_Started

Ulicsak, M., Wright, M., & Crammer, S. (2009). Gaming in families: A literature review. Slough, UK: Futurelab at National Foundation for Educational Research in England and Wales.

UPIAS (1975). Fundamental principles of disability. London, UK: Union of the Physically Impaired Against Segregation.

Vanderheiden, G.C. & Henry, S.L. (2003). Designing flexible, accessible interfaces that are more usable by everyone. Proceedings of the 2003 CHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI 2018).

Vidal, J.J. (1973). Toward direct brain-computer communication. Annual Review of Biophysics and Bioengineering, 2(1), pp. 157-80.

Yuan, B., Folmer, E., & Harris, F.C. (2011). Game accessibility: a survey. Universal Access in the Information Society, 10(1), pp. 81-100.

Zhang, Z. (2012). Microsoft Kinect sensor and its effect. IEEE MultiMedia Magazine, 19(2), pp. 4-10.

A/V Material

Street Fighter (Street Fighter). (2016). BrolyLegs: The Fighter. [YouTube video]. Retrieved from https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=s1MYSgy4QMw&feature=youtu.be

Ludography

Artemis Spaceship Bridge Commander, Incandescent Workshop, United States, 2010.

Asteroids, Atari, United States, 1981.

Double Dragon II: The Revenge, Technōs Japan, Japan, 1990.

Family Ski, Namco Bandai, Japan, 2008.

G1 Jockey, Koei Tecmo, Japan, 2008.

Keep Talking and Nobody Explodes, Steel Crate Games, Canada, 2015.

Punch Out!!, Nintendo, Japan, 1990.

Ski, Magnavox, United States, 1972.

Table Tennis, Magnavox, United States, 1972.

Author’s Info:

Mathew Dalgleish

University of Wolverhampton

m.dalgleish2@wlv.ac.uk