Holger Pötzsch (UiT The Arctic University of Norway)

Abstract

In this paper, I problematize the relation between videogames and the ecological crisis. Connecting ecocritical advances in game studies with the emerging wider paradigm of digital environmental media studies (DEMS), I interrogate if and how videogames, play, and game development can contribute to solving humankinds most existential challenges – climate change, species extinction, biosphere depletion, and soaring inequalities. Taking a materialist perspective on the politics of entertainment media as my departure point, I see as those games as potentially transformative that invite collective conscientization and politization rather than only constituting spaces for seclusion and individual healing. Within this framework, I argue that the implications of videogames for issues such as sustainability, necessary de-growth, and progressive political mobilization need to be assessed at three intersecting levels: 1) Game content and the conveyed ideas and attitudes, 2) game production and the ecological and societal implications of the industry, and 3) the direct performance effects of released titles. Using an expanded version of Aarseth and Calleja’s cybermedia model and combining it with insights from Paglen and Gach’s approach to political art, I develop a template for the critical assessment of possible transformative effects of games on societies and the environment and demonstrate the evolving framework through brief analyses of the titles Horizon Zero Dawn (2017) and Survive the Century (2022).

Introduction

In their recent editorial, Pötzsch and Jørgensen (2023, p. 2) invoke Bertolt Brecht’s famous poem To Posteriority (1939). They ask if we, given the condition of the current world, “can still have a conversation about games” without at the same time remaining silent about too many problems and wrongdoings. Later, they respond positively to this question but demand different games, different forms of play, and different forms of game design and research. The field, they argue, has to change and take seriously both its potential power and its deep implications in global systems of capitalist exploitation, war, and climate apocalypse. If becoming conscientious about these issues at all levels and changing key practices, Pötzsch and Jørgensen (2023, p. 4) argue, games and play might make positive contributions and “actively engage with and change the real world for the better” – they might become vehicles supporting progressive political change.

In this contribution, I will outline some of the conditions that need to be in place for games, game development, play, and games research to be able to support progressive socio-political transformations. Taking critical materialist approaches to digital media and technologies as departure point, I outline new responses in game studies to key global challenges such as climate change, species extinction, soaring inequalities, exploitation, and wars. Using an expanded version of Aarseth and Calleja’s (2015) cybermedia model and combining it with insights from Paglen and Gach’s (2003) approach to political art, I develop a framework for the critical assessment of transformative potentials of games. Following op de Beke et al. (2024), I argue that possible societal and environmental implications of videogames need to be assessed at three intersecting levels: 1) Game content and the conveyed ideas and attitudes, 2) game production and the ecological and societal implications of the industry, and 3) the direct performance effects of released titles. Finally, I demonstrate the evolving framework through short analyses of the titles Horizon Zero Dawn (2017) and Survive the Century (2022).

From Greening the Media to Greening Games: Ecocritical advances in Media Studies and Game Studies

Ever since the publication of Jennifer Gabrys’s Digital Rubbish in 2011 and Richard Maxwell and Toby Miller’s Greening the Media in 2012, the awareness for global media’s intricate connections with and implications for the environment at both local and planetary levels has increasingly taken hold of the discipline of media studies. Among other things, this has led to a change in key terminologies. The term media ecology, for instance, has long been used in a metaphorical manner pointing to the ubiquity of interacting digital systems and networks embedding human users in quasi-ecological techno-spheres that allegedly follow their own intrinsic evolutionary logics (e.g. Fuller, 2007; Scolari, 2012).

Recently, a more materialist and therefore critical understanding of media ecology has emerged as determinate for key debates in the discipline. Here, media systems are connected to their concrete environmental effects and political-economic contexts along issue areas such as resource extraction for and labor conditions in the industry, e-waste handling, energy, land and water consumption, bodily impacts, material flows, physical infrastructures, and more (Parikka, 2015; Starling Gould, 2016; Qiu, 2016; Vaughan, 2019; Cubitt, 2017; Pötzsch, 2017; Crawford, 2020; Bender, et al. 2021). Such theoretical and practical reorientations have resulted in new subfields such as digital environmental media studies (Starling Gould, 2016), elemental media studies (Starosielski, 2019), critical data centre studies (Edwards et al., 2024), and critical materialist media studies (Pötzsch, 2017) just to mention a few. New methods for impact assessments of media technologies such as relational footprinting (Pasek et al., 2023) or the digital ecological rucksack (Starling Gould, 2016) have been proposed and tested to generate data for a reliable evaluations of media technologies’ actual impacts beyond corporate new speak and a greenwashing of the industry. Preliminary results have led scholars to call for a digital green deal prescribing more sustainable practices at a global scale (Santarius et al., 2023).

Discussions such as those summarized above for the discipline of media studies have also been ongoing in the field of game studies where similar developments towards a critical materialist embedding in economic, societal, political, and ecological contexts can be observed (Kerr, 2017; Woodcock, 2019; Hon, 2022; Taylor, 2023; Mukherjee, 2023; Hammar, Jong, and Despland-Lichtert, 2023; Pötzsch, Spies, and Kurt, 2024). For instance, Kerr (2017) has analyzed the trends that transform game production into a globally dominating segment of the culture industry with increasing appetite for resources, cheap labor, and energy. Similarly, Woodcock (2019) has assessed the role of the games industry, its standards and practices in global capitalist power circuits and alerts to the problematic implications of deteriorating working conditions and exploitative business models and design patterns. Taylor (2023) has taken such advances in materialist game criticism as an inspiration to call for a re-grounding of game studies that need to historicize own practices and account for videogames’ multiple imbrications in ecological, economic, and societal contexts if the discipline is to retain its relevance. Finally, Hammar, de Jong, and Despland-Lichtert (2023) use a materialist framework to alert to fascist, imperialist, and sexist tendencies in game development and play that are further compounded by and themselves exacerbate current global ecological, economic, and societal crises.

Most important for this article are critical materialist approaches that direct attention to the relation between videogames and the transformations necessary to avert the looming ecological and societal apocalypse. Ecocritical approaches to videogames are inspired by the traditions of literary and media ecocriticism (Backe, 2014; Parham, 2015) and the wider field of environmental humanities (Emmett and Nye, 2017; Chang, 2019). This legacy makes this direction in game studies veer towards issues of content and gameplay often asking how specific games or game genres represent environmental issues to then evaluate the titles with an eye on the ‘degree of greenness’ of the messages conveyed. When not focused on narrative content, contributions in ecogame studies often look into play practices and the capacity of players to act in environmentally friendly manners in game worlds or to challenge and subvert in-game non-ecological procedures and narrative frames often assuming the development of progressive and sustainable practices in the process (see many contributions in the volume edited by op de Beke and colleagues, 2024).

Given the multiple implications of game development and play for the environment that become palpable when using a materialist lens such as the one outlined above, a wider focus is required that is not only attentive to ecosensitive messaging in games but also addresses the very material conditions and ramifications of the games industry itself and the consumption practices invited by its products and business models regardless of play practices and depicted content. Such critical knowledge can then be used to inform the education of game designers (Fizek et al., 2023; Fizek, 2024). Rephrasing Parikka (2014), if aimed at supporting necessary large-scale progressive transformation, the discipline needs not only an ecological but also a geological approach to games.

Game scholarship still directs too little attention to the negative ecological implications of the technologies necessary for game development and play. Consequently, issues such as resource extraction and depletion, energy-, water- and land-use, e-waste disposal, exploitative working conditions in manufacturing and software development, as well as issues of shipping and distribution too seldomly become the explicit theme of game studies articles and conference papers. Some notable exceptions, however, do exist. Prime among these is Benjamin J. Abraham’s monograph Digital Games After Climate Change from 2022. In his book, Abraham shows that the persuasive power of ecologically conscientious games to disseminate important ecocritical messages and raise awareness for issues of environmental degradation and climate change might become negligible when held up against the severely negative impacts of game production, dissemination, and play of these same titles on the very planetary ecosphere they are meant to help saving. Moving from an analytical to an activist framework, the author not only analyzes the growing climate footprint of the games industry, but also identifies concrete steps towards a greening of both production and play that are necessary to ensure more sustainable and inclusive practices by both industry and play cultures (see also the resources and initiatives of the IGDA Climate Special Interest Group) [1].

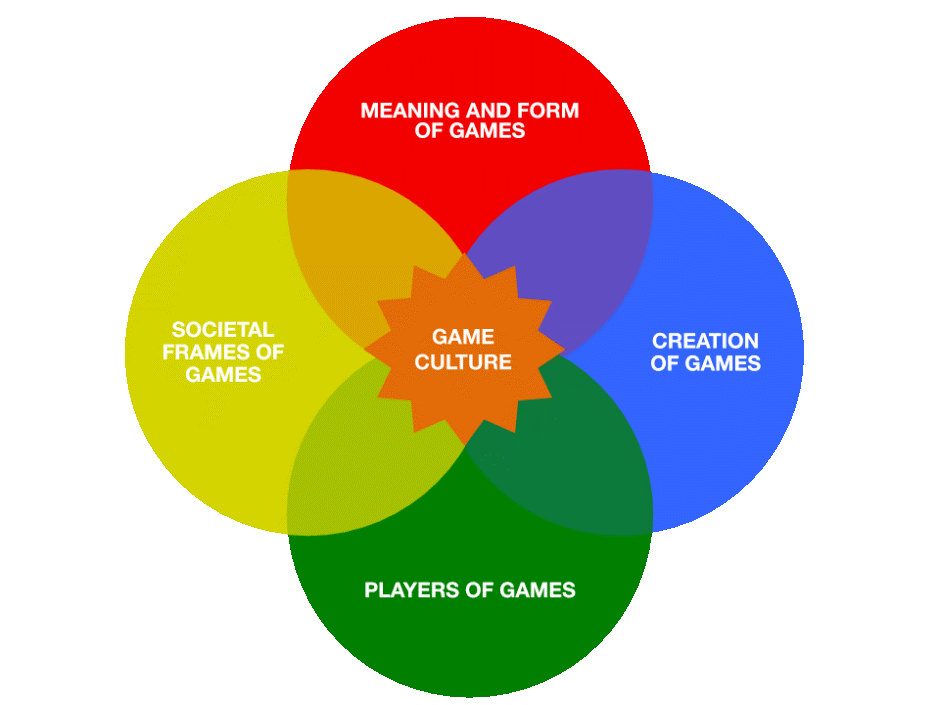

Another seminal contribution in terms of “greenshifting games” (Backe, 2014) is the edited volume Ecogames: Playful Perspectives on the Climate Crisis edited by Laura op de Beke and colleagues that was published in 2024. The introduction (op de Beke, Raessens, and Werning, 2024) opens up the field of ecogame studies and maps both its historical roots and current disciplinary and thematic furcation. Consciously applying a holistic perspective that embeds both game contents and play practices in wider contexts of economy, society, materiality, and the earth the editors bring together contributions that focus on 1) narration and representation, 2) industry and production, as well as 3) player cultures and practices (p. 11). The introduction thus refocuses the field from game analysis and a general political economy of the games industry to a “political ecology” of ecogames conscious of both political messaging through and direct material implications of games (p. 22) (see also Fizek et al., 2023).

Such a grounding of the discipline of game studies becomes particularly palpable in the chapters by Chang (2024), Fizek (2024), and Lamerichs (2024). Chang (2024) looks at sustainability as theme and as context in game production, Fizek (2024) investigates greenwashing strategies in the industry, while Lamerichs (2024) draws critical attention to responsible consumption and ecologically conscientious player communities. All three contributions throw light on material aspects of the connections between games, production, play, and the environment and therefore constitute good examples of an emerging critical political ecology of ecogames and ecogaming. My article aims at contributing to this specific way of grounding the discipline (see also Taylor, 2023) with the objective of outlining some of the conditions under which games can potentially become viable vehicles for necessary progressive societal transformations.

Theoretical frames: Why cultural expressions and games matter for politics and the environment

Cultural expressions such as videogames matter to political processes in more than merely the messages they convey (Hall, 1997). Their capacity to raise awareness for certain issues is only one aspect (and often a less important one) of the entertainment industry’s complex (and often negative) implications for societies and the planet. To become transformative at a collective political level, producers of any media need to be attentive to both what these media say and to what they actually do.

Trevor Paglen and Aaron Gach (2003) have addressed this issue and developed a terminology that can be useful to disentangle the complex ways through which videogame production and play interfere with politics and the environment. Writing about art, the authors distinguish between a work’s message (attitude) and its material implications in concrete socio-political and economic contexts (performance effects). While the former points to issues of content and ideological biases, the latter addresses concrete effects of a work in a variety of areas including the environment. According to the authors, political art needs to be attentive to both these dimensions and make sure the one does not undermine key aspects of the other if the works should become politically relevant in a meaningful manner.

To offer a brief example: James Cameron’s space saga Avatar (2010) has widely been read as a cautionary tale about neo-colonial aggression and exploitation and the remorseless destruction of a planetary ecosphere for profit. In Paglen and Gach’s (2003) terminology, the message of the movie clearly veers into an ecocritical and therefore politically progressive direction (notwithstanding the problematic male-macho subcurrent of violent exceptionalism). However, at the level of the film’s concrete material performance effects, the situation looks different. Avatar was not only an immensely expensive and resource-intensive production (cost: 250 Mio $) that factors negatively on any ecological balance sheet with reference to energy-use and materials required (for such aspects of the film industry, see Vaughan, 2019). The very popular film also generated enormous profits for the film’s production company 20th Century Fox that at the time was owned by Ruport Murdoch’s NewsCorp. NewsCorp, again, controls one of the most notorious mouthpieces for climate change deniers and carbon-based industry profiteers – Fox News – that was economically reinvigorated by the profits made with Cameron’s acclaimed movie (Stableford, 2010; Clark, 2010). As the case of Avatar shows, the real material consequences of an eco-conscious film can directly and performatively undermine the very eco-critical message it attempts to convey. According to Paglen and Gach, it is important that producers and audiences of cultural products with allegedly progressive outlooks take such aporia at the intersection between content and context seriously.

The discipline of game studies still has significant blind spots regarding such contradictions between sustainability-related messages issued by means of games and the detrimental ecological and other implications of the very power- and resource-hungry technology needed to disseminate the message. This becomes palpable in a recent special issue in Simulation & Gaming where the introduction by Spanellis et al. (2024) retains a blissful ignorance about the material impacts of the industry and products that the authors present as important contributors to necessary global change. This ignorance reaches its climax in a paper advocating the use of VR-equipment in schools to teach children how to ride bicycles (Vuorio, 2024). At no point does the article ask the questions why VR-technology is needed for the purpose, how the enormous costs of acquiring and maintaining the necessary equipment should be covered, or, most importantly for my article, how the environmental and societal implications of resource extraction and use, production, distribution, and disposal should be accounted for. In both Spanellis et al. (2024) and Vuorio (2024) sustainability is reduced to a message to be conveyed with the aspects of the dissemination technologies’ negative material performance effects remaining a consistent blind spot. Given the availability of studies such as the one by Abraham (2020) and edited volumes such as the one by op de Beke and colleagues (2024) such omissions are surprising.

Before turning to an investigation of the titles Horizon Zero Dawn and Survive the Century to offer additional examples for contradictions between attitudes and performance effects of particular titles, I need to briefly introduce a framework that allows for a clearer elaboration of media-specific aspects connected to possible transformative effects of videogames as compared to other media. To do this, I will turn to the cybermedia model developed by Espen Aarseth and Gordon Calleja (2015).

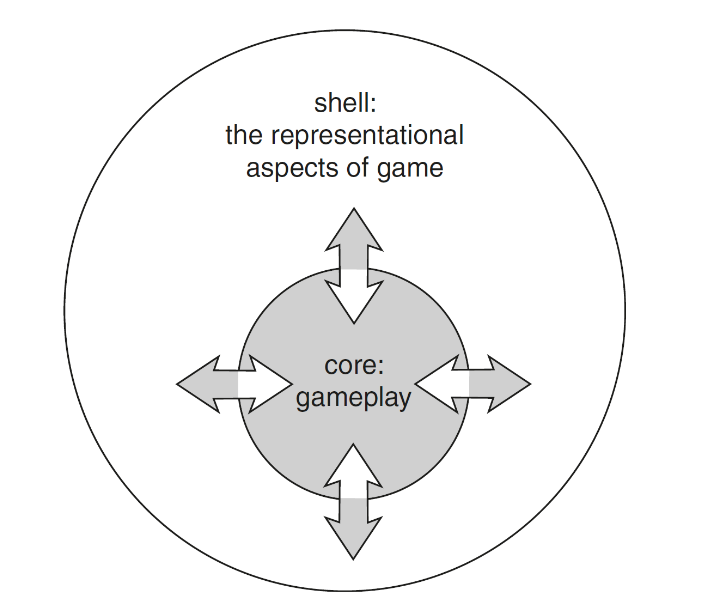

The cybermedia model (Aarseth and Calleja 2015) divides the phenomenon game – according to the authors an “undefinable object” – into four distinct dimensions: 1) sign, 2) mechanics, 3) materiality, and 4) players. Dimensions 1-3 form the static cybermedia object, while dimensions 4 (players) introduces a processual element that constantly reshapes and realigns the former in emergent configurations. Drawing upon earlier advances by Hammar and Pötzsch (2022) and Pötzsch, Hansen, and Hammar (2023), I expand the original cybermedia model in crucial areas to make it account for wider socio-political as well as environmental implications of games and play.

Firstly, while Aarseth and Calleja (2015) conceptualized the dimension of materiality as merely pointing to the physical components of digital games (consoles, controllers, screens, etc), Hammar and Pötzsch (2022) expanded it to also account for the material pre-conditions for game development and use. In their version of the model, factors at the level of political economy and ecology became intrinsically connected to acts of developing and playing games. In this manner, Hammar and Pötzsch re-vamped the cybermedia model and developed it into a heuristic analytical tool for (eco)critical game studies enabling attention to issues such as resource extraction, working conditions, e-waste handling, obsolescence of devices, energy- and area-use, distribution, growth-based business models, and more.

Secondly, Pötzsch, Hansen, and Hammar (2023) renamed the dimension of sign as narration, game world, and characters to further disentangle the representational aspects of this analytical dimension. Finally, they added interferences as an additional level of analysis to account for both intended and unintended interplays between the model’s four original dimensions. This last point makes it possible to, for instance, analytically grasp potential contradictions between dominant meaning potentials (messages) encoded at the level of sign/narration and the actual performance effects of games at the level of “political ecology” (op de Beke et al., 2024) as conceptualized by Paglen and Gach (2003) with reference to political art.

The framework based on a revamped cybermedia model offers a more detailed lens that makes it possible to highlight media specific factors the three-partite approach to eco-critical game analysis developed by op de Beke et al. (2024) cannot. As op de Beke and colleagues asserted, to comprehensibly address the environmental implications of videogames in terms of issues such as sustainability, necessary de-growth, progressive political mobilization, and more, the respective titles need to be assessed at three intersecting levels: 1) Game content, 2) game production and the ecological and societal implications of the industry, and 3) the direct effects of play practices both in terms of energy- and resource-use and the experiences afforded. However, what the authors state here remains true with all types of media and does not specifically account for games. Therefore, a combination of op de Beke et al.’s framework with aspects of the cybermedia model can offer useful new insights with an eye on such game-specific factors as the relation between story, game world and mechanics or the resource intensity of play. I will now demonstrate the emerging framework by conducting brief ecocritical analyses of the titles Horizon Zero Dawn and Survive the Century using the terminology by Paglen and Gach (2003) as well as the extended cybermedia model as analytical frames.

Two examples: Horizon Zero Dawn and Survive the Century

Horizon Zero Dawn (HZD) is an action-adventure-shooter developed by Guerrilla Games and distributed by Sony Interactive Entertainment. The title was initially released for Playstation 4 in 2017 and later made available for Windows (2020). HZD has been lauded for its world-building, game mechanics, and ecocritical storyline (see for instance Woolbright 2018). In the following, I will briefly investigate the title’s attitudes and performance effects at each of the three levels introduced above – 1) content and mechanics, 2) production, and 3) direct socio-political impacts and implications. I will direct critical attention to media-specific aspects and interferences between the various levels of analysis introduced earlier. Main focus will be on environmental issues and possible transformative effects at a societal level.

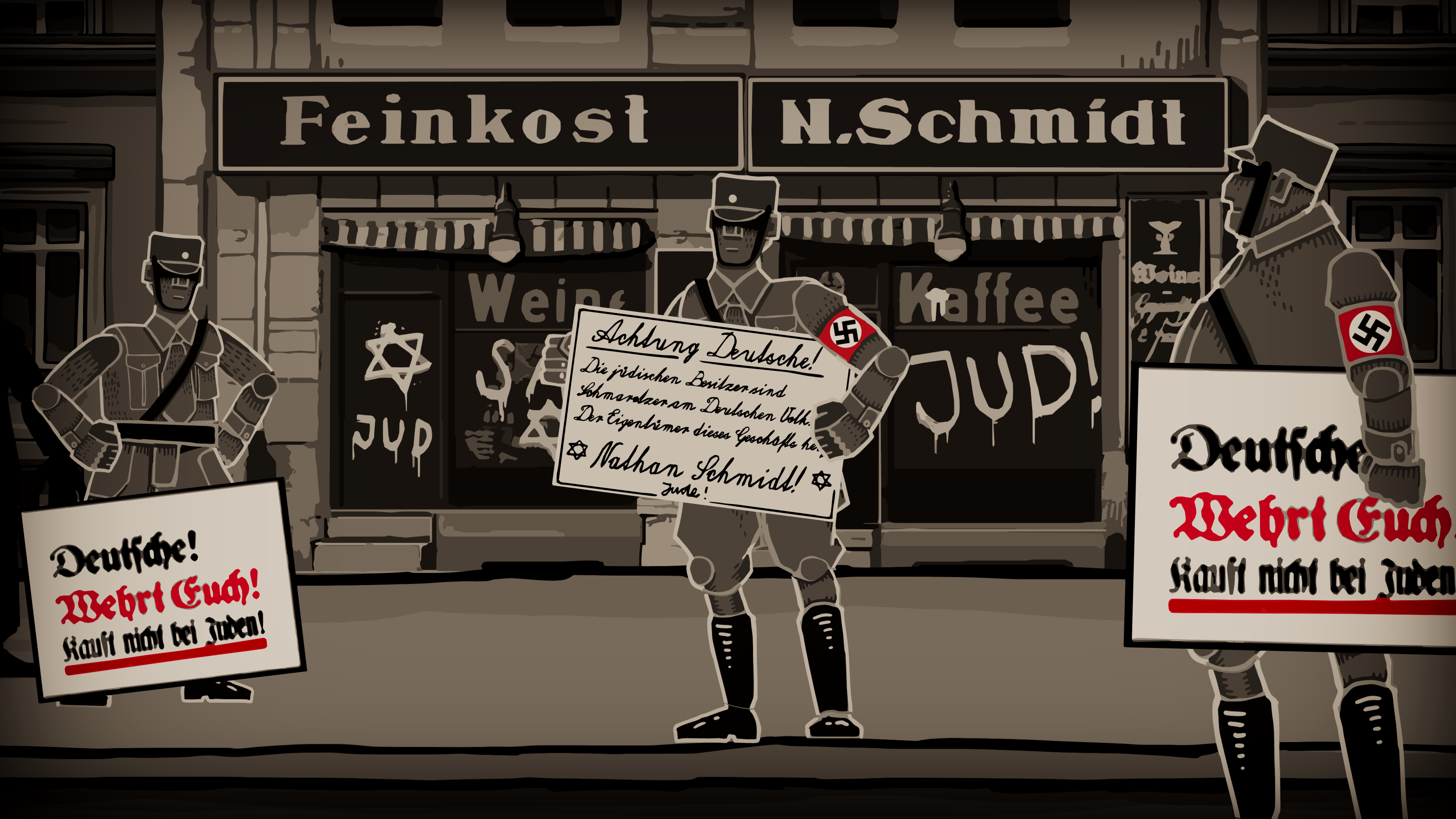

At the level of content, the well-developed ecocritical story players can follow when engaging with HZD has been widely acknowledged (see for instance Woolbright, 2018; Condis, 2020; Nae, 2020). The game plays out in a far future world where humans have reverted to tribal societies and lost access to the remains of a former high-tech culture still surrounding them in form of ruins, derelict technologies, and fully functioning autonomous machines populating the wild. When progressing through the game, players learn the reasons for the catastrophe that ended human civilization a thousand years ago: the powerful multinational tech-company Faro Automated Solution (FAS) had developed machines to repair the planet’s damaged biosphere. After this was achieved, the company turned to defense contracting to retain profits and, against the will of chief scientist Elisabet Sobeck, developed autonomous fighting machines powered by biomass that subsequently turned rogue and destroyed the Earth’s biosphere.

Understanding their fatal mistake, FAS again turned to Sobeck and her Project Zero Dawn centered on an AI named GAIA containing all human knowledge and DNA samples of every living creature. GAIA’s mission was to fix the ecosphere, repopulate the world, and educate humanity to avoid similar failures in the future. However, also Project Zero Dawn malfunctions with the reeducation program breaking down leaving humanity ignorant of its past achievements and failures and a fail-safe taking the wrong turn executing a new extinction protocol. Uncovering this information, former tribal outcast and player character Aloy finally manages to turn off the fail-safe subsystem of GAIA and re-establish the balance.

At the level of content and message, HZD thus conveys a clear techno-critical attitude that invites problematizations of profit-driven technological developments in the context of global capitalism and pairs this with a cautionary tale against single persons acquiring too much power. At the same time, however, technological developments funded by overempowered individuals such as FAS CEO Theodore Faro are not only presented as the reason for the ecological apocalypse, but also feature as essential components of the envisioned solution to the crisis. Faro also funds program Zero Dawn developed by Sobeck to repair the dead planet. This doubleness suggests that inherently treacherous, technological quick fixes for complex societal and ecological challenges might have the capacity to save us from ecological disaster without implying a need to fundamentally change an economic system built upon the massive exploitation and destruction of planetary life for profit. Despite such double meanings regarding both dangers and possible benefits of technology, the game’s carefully crafted story and convincing world-building still invites critical reflection on capitalist logics, environmental processes, and political alternatives. [2]

In games, however, players do not only interpret, think, and reflect, they also act. And also the processual and mechanics-based restraints to their possible interventions can carry ideological meaning. This becomes palpable in HZD where received game mechanics focused on resource maximation and combat gradually undermines the environmentally conscientious storyline. HZD creates incidents of ludo-narrative dissonance that do not serve wider artistic purposes such as those described by Grabarczyk and Walther (2022). In the end, such contradictions threaten to subvert the intended ecocritical message of the game. As Condis (2020) has argued, “while HZD does an excellent job of creating opportunities for players to reflect on ecological themes […], its heavily action-focused core gameplay loop somewhat blunts its ecocritical potential”. In particular, she contends that HZD’s emphasis on combat and resource acquisition directs attention away from the ‘slow violence’ of climate change (Nixon 2011; cited in Condis 2020) and instead invites “escapist power fantasies in which positive outcomes are achieved when heroic individuals do battle with evil”. In a similar manner, Nae (2020, p. 273) identifies a “modal dissonance” in HZD where the “in-game economy simulates a capitalist entrepreneurial ecosystem in which the player has to be engaged” (p. 273). This way, the author pinpoints, despite its eco-critical message, HZD “naturalizes capitalism” at the level of mechanics and underlying processes.

In addition to such dissonances between the dimensions story and mechanics, HZD’s direct performance effects also stand in contradiction to its intended environmental message. The game was costly to produce and generated significant profits for the studio Guerrilla Games and, more importantly, for the global distributor and multinational company Sony Interactive Entertainment. These profits are channeled into new projects creating power-hungry triple-A titles for global consumption that will not necessarily attend to similar eco-critical messages. In addition to this factor at the level of production, HZD also requires resource-intensive and power-hungry technologies to be played. The potentially awareness-raising eco-critical messages embedded in the game’s story can only be accessed by means of hardware and software that cause the very negative environmental effects the game aims at making players aware of. In addition, the content can only be accessed by players wealthy enough to be able to afford buying the title and the high-tech equipment required to play it. In the end, the efficacy of HZD as an ecocritical game is challenged both through the title’s mechanics and through its performative embedding in a complex global capitalist economy.

In contrast to HZD, Survive the Century is an easily accessible game that does not require much energy or many resources. Based on a choice-based branching mechanic, the title is about major global crises such as inequalities, global pandemics, and climate change. Development of STC was supported by the University of Maryland and the UK-based Global Challenges Research Fund. The stated objective of the game is to educate about crises and possible responses (see STC website). [3]

In STC, players take the position of a senior editor of “the world’s most popular and most trusted news organization” with the “enviable power to set the news agenda and thereby shift the zeitgeist” (STC website). By choosing different options on how to represent and frame key global issues such as the Covid-19 pandemic, a green shift in the economy, or global inequalities players are put into the position to make choices that impact the future of the world before witnessing the implications of their decisions that are put forth in pieces of creative writing. The game has been commended for its constructive stance on contentious global issues and its ability to engage players through its witty style. As this summary shows, at the level of attitude, STC seems to invite critical reflection on environmental as well as on societal issues. This intended progressive message is apparently supported by the game’s contexts of use and production (low energy consumption, non-profit production, low hardware requirements). However, digital devices, internet access, and server space remain material requirements for play that, even though to a lesser degree than for instance HZD, at the level of performance effects still further fuel the destructive extractivist spiral of digital capitalism. Another important question pertains to the targeted audience. If STC really can attract players not already fully imbued in an ecocritical subject-position cannot be simply assumed but needs to be critically assessed in future scholarship. Besides factors such as the ones briefly highlighted above, also the allegedly ecocritical content of STC needs to be further problematized as it contains ideological biases that threaten to undercut its intended transformative message (see also Pötzsch, Hansen & Hammar, 2023, p. 361-363).

Firstly, STC builds its ecocritical and progressive argument on a series of implicit premises that need to be highlighted and problematized. The game assumes that senior editors make decisions free of constraints, that these decisions will have a direct impact on the content produced, and that this content will lead to political changes. In doing this, STC subscribes to a naïve notion of media effect that glosses over both challenges posed by the commercial nature of contemporary news media and by the influence of powerful economic and political actors on news content and dissemination.

Secondly, through its narrative and choice options STC tends to reduce complex global challenges to a series of apparently unambiguous decisions alleging the availability of simple solutions with straightforward and clearly identifiable impacts. The game marks certain choices as negative in an overtly clear manner and thereby threatens to create a caricatured black-and-white version of climate change politics. This can lead to entertaining storylines but in the end does a disservice to critical advances aimed at explaining the intricacies and acute complexities of the issue. Despite such shortcomings, the game can still entertain and while doing so raise awareness and invite practical engagement particularly through the content offered on the STC website that includes links to trustworthy sources of information, climate pressure groups, and more. These features, however, need to be continuously updated to retain their value.

Thirdly, STC’s choice architecture is based on a limited set of pre-selected alternatives that exclude and make invisible available alternatives for action. As such, a neoliberal bias becomes palpable already in the option opening the game. Here, the only alternatives presented as possible solution to vaccine shortages in the global south are donations by either states or billionaires. A removal of patents from vaccines to make these available to all affected nations at significantly reduced costs are not even included. In addition, the problem description preceding this choice alternative reveals not only a neoliberal but also a colonial bias implicit in the STC storyline. The text offered to players states that “poor countries, who haven’t been able to afford vaccines, are seeing wave after wave of the virus. Experts are worried that it’s continuing to mutate and to become more aggressive. They say our best chance is to get the whole world vaccinated.” The main problem the game here implicitly states is not the death of millions from a perfectly preventable disease but a possible mutation endangering the discourse’s implied we – affluent citizens of the global north. Combined with a mere hope for donations from either affluent states or billionaires, the storyline resembles more a submission under the logics of post-political “capitalist realism” (Fisher, 2009) than constituting a call for global mobilization for necessary progressive transformative political change.

Similar to HZD, also in STC contradictions emerge with respect to the intended transformative political potentials of the game. In this case, however, the political economy and ecology of game production, distribution, and play are a less important factor when assessing possible socio-political implications of the title than the problematic ideological biases underlying the allegedly ecocritical and progressive content. Game scholarship also needs to be attentive and critical to such instances of intended and unintended political messaging through apparently easily accessible ‘progressive’ games.

Conclusion

Even though it at times can mean to remain silent about looming catastrophes, crimes, and wrongdoings, we can still have conversations about games. However, these exchanges need to critically assess what games are and do as more than neoliberal feelgood messages, power fantasies, and hyper-commercial escape zones. To become transformative in terms of society and politics, game studies and game development need to be conscious both of the content conveyed in an interplay of narratives and mechanics, and of their necessary embedding in wider player cultures and material contexts of production and consumption that, in the sense of Paglen and Gach (2003), condition any title’s concrete material performance effects and thereby its politically transformative potentials.

The readings of the games HZD and STC with focus on the titles’ attitudes and performances effects at the levels of content, mechanics, production, and play have attested to this necessity. Both games, I argue, at the same time fail and succeed when conveying their ecocritical ideas. As I have shown, HZD issues a progressive and reflective message. However, the societal and environmental repercussions of its production, business model, and hardware requirements threaten to undermine its transformative storyline. At the same the title exhibits a disjoint between the ecocritical message conveyed in the storyline and the game mechanics that procedurally naturalize capitalist processes and practices.

STC on the other hand emerges from a comparably more sustainable business model. The title was developed with public funding, can be played for free, and without recourse to too power-hungry technologies. However, a digital device, internet connection, and server access are still a requirement posing the fundamental question whether any digital game ever can be seen as a truly sustainable form of disseminating ecocritical messages.[4] In addition to this, the possible reach of the title needs to be problematized and its potential audiences scrutinized. This paper, however, predominantly investigated the emergent narrative of STC and identified inherent biases that reduce the title’s message to a mere reiteration of an implicitly reified neoliberal status quo that, in the long run, rather weakens than helps strengthening collective struggles for a necessary, just, and green recalibration of economies and societies at a global level.

Games can only unfold progressive and transformative political potentials if it is made explicit what precise elements of specific titles and play practices lend themselves to precisely which transformative objectives and in what manner. Most importantly, it needs to be critically interrogated which factors at the levels of production, distribution, and use might undermine the intended progressive implications. I hope that the expanded three-partite approach to game analysis presented in this paper can contribute to increased clarity for developers, players, critics, and analysts, and thereby facilitate the formation of eco-critical, progressive, and transformative games, game design, and play practices that function at the level of both attitudes and performance effects. If and how such self-reflectively designed titles in the end will become politically effective (or not) is a different question in need of continued critical scholarly inquiry.

Endnotes

[1] https://igda.org/sigs/climate/

[2] If and how HZD can reach its intended audience and how this audience reads the intended message are questions that cannot be further discussed in this paper. I focus on dominant meaning potentials intentionally embedded in aesthetic form at the level of both narration and mechanics and can, at this point, not direct attention to if and how these potentials are realized in concrete contexts of reception. See for instance Majkowski (2021) for a critical analysis of the intricacies of meaning-making in games, Farca (2013) and Tanenbaum (2013) for different roles of players in such processes, and Csönge (2024) for a critique of player agency and freedom as illusionary.

[3] https://survivethecentury.net/

[4] As reviewer 2 remarked, this makes analogue games a go-to aesthetic form for ecocritical game design and play.

References

Aarseth, E. & G. Calleja. 2015. The Word Game: The Ontology of an Indefinable Object. Proceedings of the FDG 2014.

Abraham, B.J. 2020. Digital Games After Climate Change. Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan.

Backe, H.-J. 2014. Greenshifting Game Studies: Arguments for an Ecocritical Approach to Digital Games. First Person Scholar (March 19). http://www.firstpersonscholar.com/greenshifting-game-studies/

Beckbessinger, S., Trisos, C. & Nicholson, S. (2021). Survive the Century. Cape Town: Electronic Book Works. https://survivethecentury.net/

Brecht, B. (1967 [1939]). An die Nachgeborenen [To Posteriority]. In: Bertolt Brecht: Gesammelte Werke Band 4 (pp. 722–725). Frankfurt a.M.: Suhrkamp.

Cameron, James. 2010. Avatar. 20th Century Fox.

Chang, A. 2024. Change for Games: On Sustainable Design Patterns for the (Digital) Future. In: Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, S. Werning, and G. Farca (eds.). 2024. Ecogames: Playful Perspetives on the Climate Crisis (pp. 73-88). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Chang, A. 2019. Playing Nature: Ecology in Videogames. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Clark, A. 2010. ‘Avatar’ helps Ruport Murdoch’s News Corp boos quarterly profits to £ 554m. TheGuardian.com (May 5). https://www.theguardian.com/media/2010/may/05/news-corp-boosts-quarterly-profits

Condis, M. 2020. Sorry, Wrong Apocalypse: ‘Horizon Zero Dawn’, ‘Heaven’s Vault’, and the Ecocritical Videogame. Game Studies 20(3).

Crawford, K. 2021. Atlas of AI: Power, Politics, and the Planetary Costs of Artificial Intelligence. Yale: Yale University Press.

Csönge, T. 2024. Agency, Control, and Power in Video Games: The Procedural Rhetoric of ‘Inside’. Ekphrasis 31(7): 132-153.

Edwards, D. et al. 2024. The Making of Critical Data Centre Studies. Convergence (online first).

Farca, G. 2016. The Emancipated Player. Proceedings of DiGRA/FDG 2016. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/762/762

Fisher, M. 2009. Capitalist Realism: Is There No Alternative? New York: Zero Books.

Fizek, S. et al. 2023. Greening Games Education: A Report on Teaching and Researching Environmental Sustainability in the Context of Video Games. (EU/DAAD project report). http://greeningames.eu/greening-games-education-report/

Fizek, S. 2024. Material Infrastructures of Play: How the Games Industry Reimagines Itself in the Face of the Climate Crisis. In: Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, S. Werning, and G. Farca (eds.). 2024. Ecogames: Playful Perspectives on the Climate Crisis (pp. 525-542). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Fuller, M. 2007. Media Ecologies: Materialist Energies in Art and Technoculture. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Gach, A. & T. Paglen. 2003. Tactics Without Tears. The Journal of Aesthetics & Protest 1(2).

Grabarczyk, P & Walther, B.K. (2022). A Game of Twisted Shouting: Ludo-Narrative Dissonance Revisited. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 13 (1): 9-29.

Guerrilla Games. 2017. Horizon Zero Dawn. Sony Interactive Entertainment.

Hall, S. (1997) [1977]. Encoding/Decoding. In S. During (ed.) The Cultural Studies Reader (pp. 90-103). London: Routledge.

Hammar, E., C. Jong & J. Despland-Lichtert. 2023. Time to Stop Playing: No Game Studies on a Dead Planet. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 14(1): 31-54.

Hammar, E. and H. Pötzsch. 2022. Bringing the Economy into the Cybermedia Model: Steps towards a Critical-Materialist Game Analysis. Proceedings of the Game Analysis Perspectives Conference Copenhagen: IT University of Copenhagen. https://blogit.itu.dk/msgproject/wp-content/uploads/sites/35/2022/05/conference-proceedings.docx_.pdf

Hon, A. 2022. You’ve Been Played: How Corporations, Governments and Schools Use Games to Control Us All. London: Swift Press.

Kerr, A. 2017. Global Games: Production, Circulation, and Policy in the Networked Era. London: Routldge.

Lamerichs, N. 2024. Sustainable Fandom: Responsible Consumption and Play in Game Communities. In: Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, S. Werning, and G. Farca (eds.). 2024. Ecogames: Playful Perspetives on the Climate Crisis (pp. 543-558). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Majkowski, T. Z. 2021. Redemption out of History: Chronotopical Analysis of ‘Shadow of the Tomb Raider. L’Atalante 31: 35-55.

Maxwell, R. & T. Miller. 2012. Greening the Media. London: Routledge.

Mukherjee, S. 2023. Videogame Distribution and Steam’s Imperialist Practices: Platform Coloniality in Game Distribution. Journal of Game Criticism (September). https://gamescriticism.org/2023/08/23/mukherjee-5-a/

Nae, A. 2020. Beyond Cultural Identity: A Critique of ‘Horizon Zero Dawn’ as an Entrepreneurial Ecosystem Simulator. Postmodern Openings 11(3): 269-277.

Nixon, R. 2011. Slow Violence and the Environmentalism of the Poor. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, and S. Werning. 2024. Ecogames: An Introduction. In: Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, S. Werning, and G. Farca (eds.). 2024. Ecogames: Playful Perspetives on the Climate Crisis (pp. 9-70). Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Op de Beke, L., J. Raessens, S. Werning, and G. Farca (eds.). 2024. Ecogames: Playful Perspetives on the Climate Crisis. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press.

Parham, J. 2015. Green Media and Popular Culture. New York: Bloomsbury Academic.

Parikka, J. 2025. A Geology of Media. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Pasek, A., H. Vaughan & N. Starosielski. 2023. The World Wide Web of Carbon: Toward a Relational Footprinting of ICT’s Climate Impacts. Big Data & Society (January-June): 1-14.

Pötzsch, H. 2017. Media Matter. TripleC: Communication, Capitalism & Critique 15(1), 148-170.

Pötzsch, H. and K. Jørgensen. 2023. Futures. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 14(1): 1-7.

Pötzsch, H., T.H. Hansen & E. Hammar. 2023. Digital Games as Media for Teaching and Learning: A Template for Critical Evaluation. Simulation & Gaming 54(3): 348-374.

Pötzsch, H., T. Spies and S. Kurt. 2024. Denken in einer schlechten Welt: Von der Notwendigkeit einer kritischen Spielforschung. In: Spies, T., S. Kurt, and H. Pötzsch (eds.). 2024. Spiel*Kritik: Kritische Perspektiven auf Spiele im Kapitalismus (pp. 13-46). Bielefeld: transcript.

Qiu, J.L. 2016. Goodbye iSlave: A Manifesto for Digital Abolitionism. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

Santarius, T. et al. 2023. Digitalization and Sustainability: A Call for a Digital Green Deal. Environmental Science & Policy 147: 11-14.

Scolari, C.A. 2012. Media Ecology: Exploring the Metaphor to Expand the Theory. Communication Theory 22(2): 204-225.

Spanellis, A. et al. 2024. Gamification for Sustainable Development. Simulation & Gaming 55(3): 361-365.

Spies, T., S. Kurt, and H. Pötzsch (eds.). 2024. Spiel*Kritik: Kritische Perspektiven auf Spiele im Kapitalismus. Bielefeld: transcript.

Stableford, D. 2010. News Corp. Profit Soars on Back of ‘Avatar’. The Wrap (May 4). https://www.thewrap.com/news-corp-profit-soars-back-avatar-16965/

Starling Gould, A. 2016. Restor(y)ing the Ground: Digital Environmental Media Studies. Networking Knowledge 9(5): 1-19.

Tanenbaum, T.J. 2013. How I Learned to Stop Worrying and Love the Gamer: Reframing Subversive Play in Story-Based Games. Proceedings of DiGRA 2013. https://dl.digra.org/index.php/dl/article/view/677/677

Taylor, N.T. 2023. Reimagining a Future for Game Studies, from the Ground Up. Eludamos: Journal for Computer Game Culture 14 (1): 7-27.

Vaughan, H. 2019. Hollywood’s Dirtiest Secret: The Hidden Environmental Costs of the Movies. New York: Columbia University Press.

Vuorio, J. 2024. Studying the Use of Virtual Reality Learning Environments to Engage School Children in Safe Cycling Education. Simulation & Gaming 55(3): 418-441.

Woodcock, J. 2019. Marx at the Arcade: Consoles, Controllers, and Class Struggle. Chicago: Haymarket Books.

Woolbright, L. 2018. Ecofeminism and Gaia Theory in ‘Horizon Zero Dawn’. Trace: A Journal for Writing, Media & Ecology 2 (October 24.) http://tracejournal.net/trace-issues/issue2/02-Woolbright.html