Eugen Pfister (Hochschule der Künste Bern – HKB), Martin Tschiggerl (Universität des Saarlandes) 1

Abstract

History is not only the construction of a past, but is also its interpretation. In this paper we study examples of taboos in historical representations of World War II in digital games as sources for contemporary collective identities. To this end we analyze two

distinct phenomena: legal and cultural taboos determining what can be shown and what can be said in these games. We will show how a cultural and political paradigm shift has occurred in Austria and Germany in recent years. Thus, the portrayal of the Holocaust is no longer only understood as a taboo but also as a necessary part of our culture of remembrance. In a second part, we will look at how taboos are not only discussed but also co-constructed within the gaming community on the occasion of authenticity debates.

Introduction

In popular culture, history functions as a reliable selling point: historical novels, historical films, historical Netflix-series abound (cf. Samida, 2014; Cauvin, 2016). Many digital games are likewise advertised by promoting their historical authenticity and there seems to be an ongoing demand for historical content among users (Pfister, 2020). History here is not only the construction of a past, but is also its interpretation. Through this interpretation, history functions as a building block for our collective identities; it communicates values and norms (ibid). In order to illustrate this, we will use examples of taboos in historical representations of World War II in digital games as sources for contemporary collective identities. We will first explain which taboo concepts we are dealing with, in order to later analyse how they are imposed upon and received in digital games. We will investigate two distinct phenomena: First, taboos surrounding the production of the games as well as the product – the games themselves. Here, we are interested in the representation and successive way in which the use of Nazi symbols in this media and the Holocaust in digital games has been taboo over the years. To this end, we have selected games that in their representation of the Nazi era, have caused controversy: Wolfenstein: The New Order, Call of Duty: WW II and Through the Darkest of Times. In a second step, we will investigate taboos surrounding the reception of digital games that have World War II as their main theme. For this purpose, we have selected two games that have also triggered discussions in recent years due to their depiction of the Nazi era: Battlefield V and the grand strategy game Hearts of Iron IV. This reception is examined in the form of a critical discourse analysis. (Wodak et al, 2009, Jäger, 2011). Consequently, we have evaluated particularly popular threads on the social medium Reddit and in the forums of the gaming platform Steam with regard to the handling of taboos.

In our everyday use, we mostly understand “history” as the unchanging sum of all the past. In scientific understanding, however, the term takes on a different meaning. We understand history as a narrative construction of the past in the present (Tschiggerl/Walach/Zahlmann, 2019, p. 138). The depicted events (similar to a story) are shown as motivated (there is a comprehensible causal connection), and become a meaning, a world explanation (White, 1973). As such, history is always bound to the dispositives of its respective time of origin. In our modern societies, history plays a crucial role in communicating meaning and identity, not only in academia but also – and especially – in popular culture. The representation of history in games communicates worldviews and common values and is thus a good source with which to better understand our contemporary societies. We recognise taboos as social limitations of what is sayable in the broadest sense. They socially and culturally regulate what may not be said, done or shown, whether in principle it could be said, done or shown. Here, we are influenced by Michel Foucault’s concept of “discourse” as “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak” (Foucault, 2013, p. 54). Discourse governs what is considered as truth and what as lie, what is considered right and what is considered wrong. In this way, discourse not only creates meaning, but in fact constructs our reality. Discourse must thus be thought of as a social practice that is socially constructed, on the one hand, but is also socially determining, on the other (Wodak et al., 2009, p. 8). Taboos are areas of discourse that are the most affected by disciplinary measures and bans on speaking and acting. Put very simply, taboos are an effective means of defining what a collective defines as ‘good’ and what it defines as ‘bad’, and taboos, by their very nature, are intended to prevent unacceptable behaviour. The Second World War as a quasi-global lieu de mémoire is of central importance in the collective memory of our western post-war societies. This is why narratives of the Second World War are also full of cultural and political taboos. There are different ways to ensure that these taboos are observed. The most obvious being practices that are effectively regulated by law, as for example, denial of the Holocaust and other Nazi crimes, which is a criminal offence in Austria and Germany. The same applies to various forms of re-engagement in National Socialist activities and the use and reproduction of anti-constitutional signs (e.g. the swastika and SS-runes) in Germany. Apart from legal forms of regulation i.e. the criminalization of taboos – which are the exception rather than the rule, especially in the case of historical representations – taboos tend to be enforced within society itself through peer pressure and exclusion and without jurisdiction. When politicians – as has been the case recently with actors from the Austrian and German Far-Right – violate these taboos, they are usually rebuked by their parliamentary colleagues, in the media but also by the public in general. They lose social status and are excluded from certain events.

Just like discourse itself, taboos, however, change over time and things that were previously unspeakable, untouchable, and even unthinkable can gradually become part of social communication. Especially in historical research and representation we can find numerous examples of such shifts in discourse.

In the following paragraphs, we will therefore take a closer look at three distinct forms of taboos concerning the depiction of World War II in games. For one, there is the political taboo, which extends to making it illegal to reproduce Nazi symbols. Deeply interlinked with this is the cultural taboo, which makes it unthinkable to use images of the Shoah in an entertainment media. In the sense of a critical history of ideas and conceptual history, we will diachronically examine the discursive taboo strategies at work within public debate. To this end, we will look at examples of individual reactions of journalists and cultural critics to perceived breaking of taboos. A comparison of reactions to the TV-series Holocaust, the feature film Schindler’s List and to digital games such as Wolfenstein: The New Order and Through the Darkest of Times should enable us to recognise historical continuities or breaks in how these taboos have been dealt with. We are not interested in a comprehensive survey of all public reaction, but rather in identifying historical patterns. To complete this first impression we will finally reverse our initially adopted top-down approach and analyse taboos from the bottom up from the perspective of the individual players themselves through an analysis of how they receive them.

“You don’t play with the Swastika!” – A failed Political Taboo?

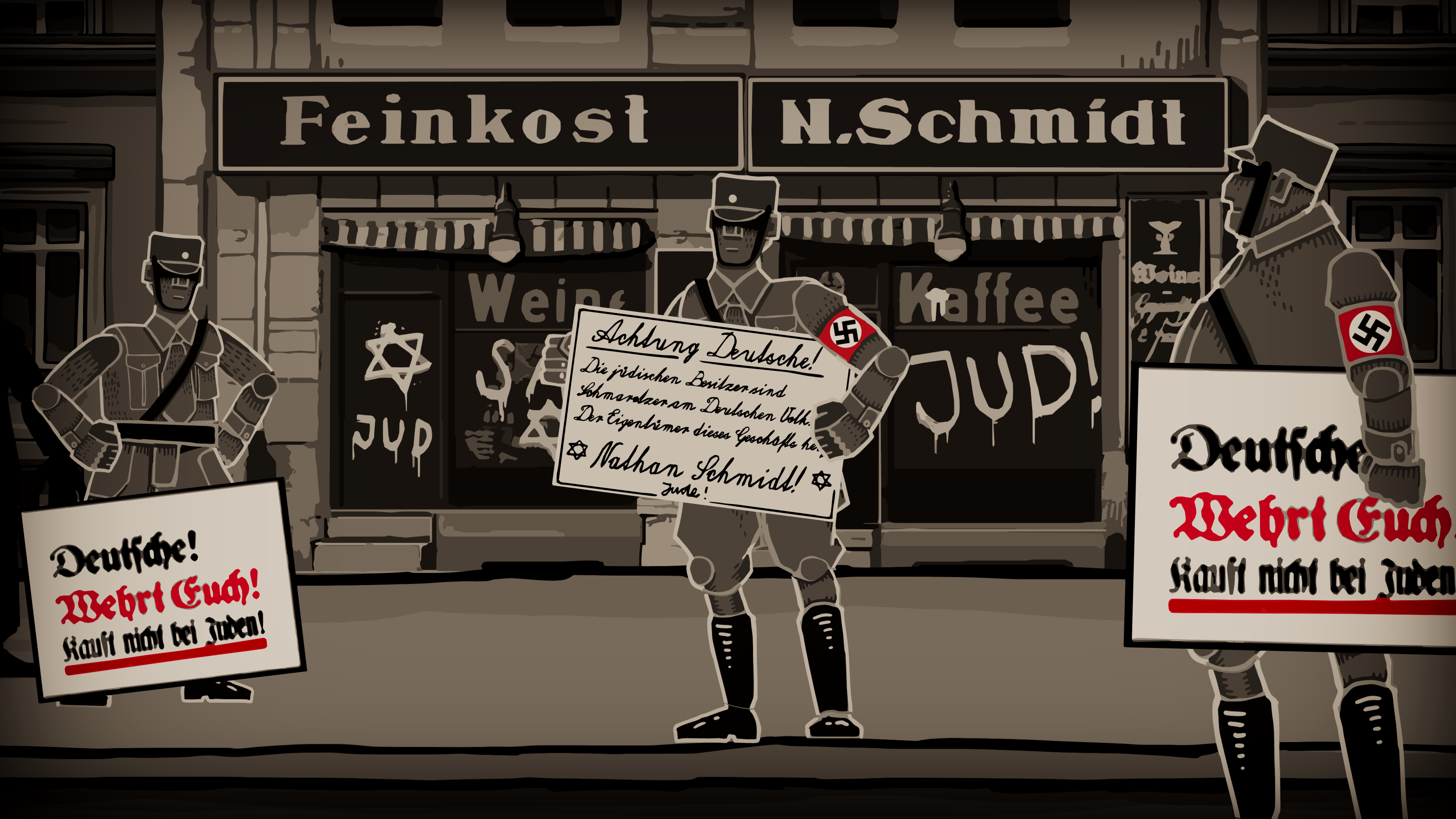

It is impossible to cleanly separate cultural taboos from legal taboos. Austria and Germany are – for obvious historical reasons – the two countries with the most restrictive legislation regarding the memory of National Socialism. In Austria, the provisional post-war government passed the so-called “Verbotsgesetz” as early as 1945, a constitutional law which banned the Nazi-Party. In its present form it became applicable in 1947 and prohibits Holocaust denial as well as the denial of other of crimes against humanity committed by the Nazi regime. The “Abzeichengesetz”, enacted in 1960, also prohibits the use of uniforms and insignia of forbidden organisations. The German equivalent are the sections 86 and 86a of the German Criminal Code (Strafgesetzbuch StGB). These cover the prohibition of the “use of symbols of unconstitutional organizations” outside the contexts of “art or science, research or teaching” (Trips-Hebert, 2014). The intention of these laws was not only to make any form of political continuity of Nazi ideology impossible but also to prohibit the use of all insignia of the Nazi regime for the future. These were to be effectively erased from everyday life. The impulse for the ban is understandable, as it was intended to make any habituation impossible (Dankert & Sümmermann, 2018, p. 6). Any use of swastikas is a taboo that was thus enshrined in law.

However, it is important to note, that there were exemptions to the ban: the so-called “Sozialadäquanzklausel” (social adequacy clause) in German law states that the use of Nazi symbols is permitted if it serves the arts, science or political education (Trips-Hebert, 2014, p. 17). The use of Nazi symbols in historical movies became so widespread that practically all films were permitted to use them (the only exception being posters advertising the films). This was not the case with digital games. In 1998, the Higher Regional Court of Frankfurt am Main ruled “that no signs of unconstitutional organisations may be shown in computer games” (Dankert & Sümmermann, 2018, p. 6). The judges understood that computer games were neither art nor history books and disallowed the social adequacy clause in their case. Up to now, the highest state youth authorities have been guided by this ruling; developers and publishers have not been permitted to submit games to the Unterhaltungssoftware Seltbstkontrolle USK (the German Entertainment Software Self-Regulation) that contain the swastika symbol. But, what is more, before the court ruling almost all game distributors had already decided to remove all Nazi symbols in the German releases of their games (Pfister, 2019, p. 275). In the German localisation of the Lucasfilm game adventure Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade (1989) all swastika symbols had already been covered by black bars. It is difficult to communicate a taboo more clearly.

There are three well-known cases of World War II games that were put on the German ‘Index’ in the 1990s, a list of media banned by the German government. This ban, however, was not because of the prohibition on the use of unconstitutional symbols in Germany. The inhuman game KZ-Manager – which gained notoriety in the early 1990s, not least because of a report in the New York Times – was put on the German “index” under the Youth Protection Act (Bundesanzeiger, 2014). Next was Wolfenstein 3D, the first first-person shooter to be set in World War II. The reason for the decision of the Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Schriften – BPjS (Federal Department for Writings Harmful to Young Persons) later renamed Bundesprüfstelle für jugendgefährdende Medien – BPjM (i.e. Federal Review Board for Media Harmful to Minors) was — contrary to popular belief — not the historical setting but the glorification of ‘Selbstjustiz’ (vigilantism) and the excessive violence of the game. Panzer General was also placed on the “index” in June 1996, but this too had nothing to do with paragraphs 86 and 86a because the game developers had renounced the use of the swastika and had instead chosen the Balkenkreuz (the military cross used by the German army) to identify the German troops. The game was placed on the index because its content was deemed to ‘kriegsverharmlosend und kriegsverherrlichend’ (downplay and glorify war), since it failed to show the consequences that the war had on the population and because it trivialised Nazi ideology (Celeda, 2015, p. 67).

The pre-emptive and superficial removal of Nazi symbols, however, did not automatically lead to a more critical depiction of the Nazi regime in digital games. On the contrary, the replacement of the swastika symbol by the “Balkenkreuz” or other symbols was understood by most publishers as sufficient distancing and thus led de facto to a continued and uncritical representation of the Nazi regime because the subject had been depoliticized (Chapman & Lindenroth, 2015, p. 146-147). In Hearts of Iron IV for example, players can micromanage the German Reich to German marching music for hours without having to deal for even a moment with the inhuman ideology of the simulated state apparatus (Pfister, 2019, p. 275-276). Indeed, the example of Hearts of Iron shows an unintended counter-effect of the ban. The problem is that the Prohibition Act was not understood in its intention, especially outside Germany. The following commentary on Steam shows that German legislation has been misunderstood on more than one occasion internationally as being a general ban on talking about the crimes of the Nazi regime: “a lot of it probably also have [sic] to do with German law. there’s a reason why his [i.e. Hitler’s] picture is blurred in the German version. if they censor that they will for sure censor a game that actually “shows” the holocaust”2 Such misunderstandings or misinterpretations were and still are quite common, as can be read, for example, in the recently published memoirs of Sid Meier. He believes, for example, despite his own experiences with German legislation, that the mere mention of the name Hitler would be punishable (Meier, 2020, p. 122). Another example for the ineffectiveness of superficial erasures can be found in the multiplayer mode of Call of Duty: World at War: players winning a match on the German side will see no swastika, SS runes or skull insignia, but a speech by Adolf Hitler to the German party youth can be heard offstage (Pfister, 2019, p. 275-276). The political taboo behind the banning of the symbols thus did not stop the insensitive handling of the historical event effectively nor prevent a possible habituation among players, but merely caused cosmetic changes.

There is one last, in our opinion, especially problematic example of misunderstood self-censure from the recent Austrian and German past: Wolfenstein: The New Colossus. While the international version propagates a conscious anti-fascist narrative (Roberston, 2017) and shows swastika symbols as insignia of an evil ideology, these have been removed on behalf of the publisher for the German version along with Adolf Hitler’s moustache. The historical narrative of the game has also been rewritten to reflect the completely fictional background of the German version. Hitler was renamed “Heiler” and the word “Jew” was replaced by the word “Verräter” (traitor). The industrialized, racially motivated murder of 6 million people thus became, in translation, the murder of political opponents. This removal of the Holocaust, in the German version, led de facto to a rewriting of history. A subsequent debate in the German media showed a decreasing support for the Verbotsgesetz (Schiffer, 2017). A central danger of the political taboo is that it could not be discussed politically, and thus made a public discussion on the topic impossible (Steuer, 2017, p. 688).

This became particularly clear when the taboo was, in effect, broken in 2018. When the German Classification Board “USK” decided after a process of internal discussions – also in response to the self-censorship in Wolfenstein –to take account of the social adequacy clause in the future when rating games by age and to permit the use of Nazi symbols in individual cases, there was an immediate political outcry. Both the German Trade Union Confederation (DGB) and Franziska Giffey, the Social Democrat (SPD) Minister for Family Affairs promptly attacked the decision. “Mit Hakenkreuzen spielt man nicht” (i.e. You don’t play with swastikas), Giffey declared (“Mit Hakenkreuzen spielt man nicht”, 2018) and was seconded by the DGB. This public expression of indignation came immediately following the USK’s announcement, and as Minister Giffey explained on her Facebook page a little later, too hastily: After playing the game Through the Darkest of Times, which is clearly opposed to the Nazi regime, Giffey admitted that the application of the social adequacy clause would be justified in this special case (Giffey, 2018). This is also where we find an explanation for the vehemence of her initial reaction when Giffey writes: “As Minister for Family Affairs, my concern is to create the framework for children and young people to learn how to use games in an age-appropriate way” (ibid.). A helpless and supposedly easily influenced population group had to be protected. The interesting thing about taboos, as can be seen here again, is that their defenders usually consider themselves immune to the dangers from which the taboos are supposed to protect. But this also means that those who stand up for and those who oppose a taboo both consider themselves to be unaffected by its effects.

The reaction of the German press and the ensuing decision of the USK showed however, that the taboo had at this point already been broken. This is not least related to a paradigm shift that had already occurred years earlier concerning an interrelated cultural taboo surrounding the Shoah.

To write a game after Auschwitz is barbaric – a cultural taboo

Parallel to the symbols of the Nazi regime becoming a political taboo, after the Second World War there was also an ongoing discussion among cultural actors whether and how the crimes of the Nazi regime – especially the Shoah – could be depicted in works of art. In this context, Adorno’s dictum “to write a poem after Auschwitz is barbaric” (Adorno, 1977, p. 30) is regularly quoted, most often interpreted as a dogmatic ban in the tradition of a religious “Bildverbot” (i.e. ban in images. cf. Krieghofer, 2017; Hansen, 1996, p. 300, 306). According to this interpretation, it would forever be impossible to adequately describe the suffering of millions of people in a poem. However, this interpretation of Adorno’s statement, which he himself relativised later on, could also be read as criticism of a culture that is inherently barbaric (cf. Lindner, 1998, p. 286). Nevertheless, from this moment on every medialisation of the Holocaust was met with the fear of trivialisation. For a long time, then, it was considered inconceivable that the Holocaust could be treated in a television series or in a feature film – the entertainment media par excellence (Pfister, 2019, pp. 269-270). Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (Steven Spielberg, US, 1993) – despite or perhaps because of its success (Classen, 2009, p. 78) – was criticised massively at the time of its release in a similar way to the TV-Series Holocaust (Chomsky, US, 1978). Fifteen years earlier, Chomsky’s TV-Series led to a heated public debate, particularly in West Germany. The journalist Sabina Lietzmann, for example, criticised how history had become a story. (Lietzmann,1979, 39). The writer and Holocaust survivor Elie Wiesel was also appalled: “I am horrified by the thought that the Holocaust could one day be measured and judged by NBC television production.” (Wiesel, 1979, 29). We will encounter similar if not the same arguments in relation to digital games.

A decade later, Spielberg’s film met with similar criticism. Claude Lanzmann, director of the Shoah documentary rejected Spielberg’s film, in particular because of its “fetishism of style and glamour” (Hansen, 1996, p. 296). The American film critic James Hoberman asked: “Is it possible to make a feel-good entertainment about the ultimate feel-bad experience of the 20th century?” (Hansen, 1996, p. 297), and Lanzman declared: “[In Spielberg’s] film there is no reflection, no thought, about what is the Holocaust and no thought about what is cinema. Because if he would have thought, he would not have made it – or he would have made Shoah” (Hansen, p. 1996, p. 301). Of course, both the TV series and Spielberg’s film also met with a positive to very positive response from the general public. Both were extremely successful with the audience, so successful, in fact, that they led de facto to a discursive paradigm shift. They changed the boundaries of what could be shown and what could be said.

Of interest to us is that similar arguments are found in critiques of digital games: “Where the line of decency is drawn is somewhat dependent on whether you consider video games art, storytelling or a braindead way to kill time, blasting pixels in increasingly gross ways while memorizing movement patterns” (Hoffman, 2014).

The first games that tried to address the Holocaust were problematic for a variety of reasons. First of all, there was a game that brutally and criminally transgressed all norms: The aforementioned KZ-Manager (unknown developer, unknown date), an inhuman shareware game that was circulated in right-wing extremist circles in Germany and Austria in the late 1980s (Benz, 1996; Nolden, 2020, p. 188). The game was quickly banned in Germany and sadly gained international notoriety through an article in the New York Times, where Rabbi Avraham Cooper, then associate dean of the Simon Wiesenthal Center, said “he believed that the games were neo-Nazi propaganda aimed at influencing youths through a technology that their parents are largely unfamiliar with” (Video Game discovered uses Nazi Death Camps as Theme, 1991).

This troublesome first contact with video games explains the subsequent scepticism of the Simon Wiesenthal Center towards video games depicting the Shoah. The taboo remained in place, which perhaps also led to the failure of the game project Imagination is the only escape (Luc Bernard, not published, 2008-2013) due to lack of financial support and the loss of Nintendo as publisher (Sridhar, 2008). The games developer, Luc Bernard, wanted to tell the fictional story of a young French Jew, Samuel, who during the Nazi occupation increasingly fled into a fantasy world in the face of the atrocities he had experienced. While the historical events took place in a monochrome sepia-coloured Paris – with the exception of individual details such as the yellow Star of David and red pools of blood – Samuel’s fantasy world was to shine in all possible colours. Bernard ultimately lost the support of his publisher and was not able to raise enough money for the project. “Labeling it a game instantly conjures up the wrong image,” said Deborah Lauter, civil rights director of the Anti-Defamation League in New York. “It devalues the seriousness of the topic” (Parker, 2016). Another example was the mod Sonderkommando Revolt which was developed for the then nearly two-decade old game engine of Wolfenstein 3D. The leading Israeli developer on the game, Maxim Genis, did not, however, display a particularly ethical approach to the topic. He claimed there was no political intention behind it: “the mod was a plain ‘blast the Nazis’ fun” (McWerthor, 2010). After an introductory black-and-white still, whose aesthetics are reminiscent of the photographs of the gas chambers secretly taken by Greek naval officer Alberto Errera, the rest of the mod is presented in bright colours and primitive graphics, which are mainly characterised by visualisations of heaped corpses, charred skeletons and vast amounts of blood. Rabbi Abraham Cooper of the Simon Wiesenthal Centre, who had taken a stand on the game KZ Manager twenty years earlier, took an understandably critical view of the game: “What happens if this is the only thing a young person gets to know about the Holocaust or a concentration camp?” (ibid), reminding us of Eli Wiesel’s words. In view of the mod, Cooper generally rejected the idea of depicting the Holocaust in video games : “I don’t think even the best combination of game developers would ever be successful [at doing so]. This is not an issue that should be reduced to a game” (ibid). Both the American Anti-Defamation League and the Simon Wiesenthal Centre were appalled and the mod was withdrawn. Again, the argumentation used to uphold the taboo was the same as that used previously for television series and feature films. It is interesting to note that the mod was almost certainly inspired by the success of Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds (and the resulting public acceptance of the Nazi exploitation genre), which shows that at this time the medium of games was still evaluated by the general public based upon completely different standards than, for example, film.

Considering these negative examples, it is all the more surprising that we have witnessed a paradigm shift in the last two years. The original moment of this shift cannot yet be satisfactorily clarified. What we can establish, however, is that the depiction of a game mission in a camp in Wolfenstein: The New Order that can clearly be decoded as a concentration camp met with little resistance in the press, apart from a critical interview about the game in the Times of Israel (Hoffman, 2014). A possible explanation would be that the scene only takes place in the advanced game and was therefore not noticed by the press on release. Of particular interest is that, unlike the mod Sonderkommando Revolt, there were no angry reactions from the Simon Wiesenthal Centre or the Anti-Defamation League. However, the game did meet with some criticism. In the Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung, the editor perceives a change of paradigm: “Man sollte aus dem Schrecklichen aber nun doch keine Komödie machen – und ein schematisches Ballerspiel vielleicht lieber auch nicht” (i.e. “You should not make a comedy out of terror – and not a schematic shoot ‘em up game at that”. Lindemann, 2014). It is difficult to see at this stage why Wolfenstein: The New Order was not attacked as sharply as the Israeli mod was a few years earlier. Maybe it was the science fiction setting, or perhaps it was the direct influence of the now seemingly socially acceptable ‘Naziploitation’ genre, which five years earlier would not have worked (Pfister, 2019, p. 277). To a certain extent, it was the popular cultural exaggeration of the topic in Wolfenstein – i.e. robot dogs, moon bases and brain-transplantation in the tradition of the last wave of Naziploitation movies such as Iron Sky and Overlord – that made it possible to break the taboo. In a way, the appearance of the pulp-fiction genre allowed the game more freedom. The Nazi crimes depicted were sufficiently distorted by their exaggeration not to be taken “seriously”. Similarily, in the Japanese strategy game Valkyria Chronicles, it is within a fantasy setting that players free “Darkscens” from a concentration camp in a mission. The strategy game, which openly spoke of concentration camps, but in the Japanese tradition of anime relied on scantily-dressed women and exaggerated gestures, was not, to our knowledge, criticised for depicting concentration camps in German-speaking countries or in Israel. But one has to admit that the game, despite its fantastic exaggeration, criticised war crimes more honestly than many games before it. In any case, however, we can discern a change in the sayable and showable around this time. This is particularly evident in the following games: In Call of Duty: WW II the picture of a Jewish concentration camp prisoner was shown for the first time (although much too briefly) in a cutscene at the end of the game and in the international version of Wolfenstein: The New Colossus the murder of Jewish women and dissidents in concentration camps was openly discussed for the first time as such. It is significant that the game was not criticised in the press for mentioning the Holocaust. On the contrary, the German press criticised the fact that it did not mention the Holocaust at all in the German version of the game: “Dieses Spiel leugnet den Holocaust” (i.e. “The game denies the existence of the Holocaust) was the first sentence of a review of the game in the German newspaper Die Welt (Küveler, 2017). When Through the Darkest of Times was published internationally at the beginning of 2020, together with Attentat 1942, the first game that received an age rating from the USK despite the inclusion of Nazi symbols, the response from the international press was extremely positive. Time Magazine recommended the game as “key to keeping World War II Memory Alive”. The American historian Robert Whitaker declared in the interview: “The game exposes players to a history most people don’t know while the game’s mechanics illustrate for the player how difficult resistance to Nazism often was for ordinary people” (Waxman, 2020).

Authenticity and User Generated Taboos

After having analysed the production of the games as well as the products – i.e. the games themselves – in the first part of our article, we will now take look at discursive taboos in the reception of games in the second part. For this purpose, we have examined and evaluated a selection of statements from players in relevant forums on social media using a qualitative discourse analysis. The aim is not to offer a complete view here – there is not enough space for this – but to offer a first insight into the process in which a theme or element becomes taboo on the part of the players, and also to highlight the differences in how taboos are received in politics and the press. The goal of a discourse analysis such as this is not only to analyse the sayable or thinkable in its qualitative range and in its accumulation or all the statements that can be made in a particular community at a particular time, but also the strategies with which the field of the sayable is narrowed (Jäger, 2011, p. 94). From the wealth of statements observed, we have selected those we particularly deem representable for the ideas presented within this article. These statements can be interpreted as hegemonic positions due to interactions made with them (likes, upvotes) and/or their frequency. Since all these statements have been made in public forums and users have done so under pseudonyms, the authors have no ethical or legal concerns in quoting them in this article.

We have observed that both taboos analysed above – i.e. a legal-political and a cultural one – have been internalised by the players in the games. Above all, this applies – as we will show in the following – to the depiction of the Holocaust and the different forms of informal image restrictions (Bilderverbot). But a closer analysis of the players conversations reveals also other forms of taboo. These do not arise from the internalisation of taboos already in place in the sense of a dominant discursive statement, but seem to have emerged from the interaction of the players in these game and the game-specific forums: The deviation from what at least a vociferous element of the game-playing community perceive as “authentic history”, is similarly sanctioned by them and is, in effect, made taboo. Especially among those players for whom the act of playing is a central component of self-identification, there is a strong urge to determine the sayable and thinkable in connection with games. These often show a particularly conservative perception of games, in the sense that they believe that games should change as little as possible in terms of content. Our central category of analysis is the discursive construction of notions of authenticity. These become tangible, above all, when players perceive historical representations as “inauthentic” – in other words, it is a negative construction ex post, the concept only emerges when previously implicit rules are broken.

Any deviations from a representation of the Second World War that is considered authentic are perceived accordingly by a small group of players as breaking something that we could call an “authenticity taboo”. In understanding this “authenticity taboo” it is important to realize that authenticity is not something that is inherent in a phenomenon – be it a digital game, an action or any kind of object – but rather a product of attribution and negotiation. Like taboos, authenticity is also a social-discursive construct. Something must be acknowledged as authentic to be authentic (Reckwitz, 2017). The producers of digital games choose different strategies to create authenticity, i.e. to get their recipients to perceive the product as authentic (Pfister, 2020, Tschiggerl, 2020).

In his reference work Digital Games as History, Adam Chapman makes a fundamental distinction between two types of digital games with historical content: “realist simulations” and “conceptual simulations” (Chapman, 2016, p. 112). These two types, as historical representations, differ not only in terms of different game mechanics and principles, but, above all, in the way they represent history and establish historical accuracy and authenticity. While “realist simulations” – Chapman counts among them mainly third or first-person video games such as the Medal of Honor (Dreamworks Interactive et al., US 1999-2012), Call of Duty (Infinity Ward u.a., US, 2003-2019) or the Assassin’s Creed (Ubisoft Montreal et al., Canada & France, 2007-2018) series rely on audio-visual narratives in their mediation and thus show, as it were, “conceptual simulations” according to Chapman, primarily strategy games such as the Sid Meier’s Civilization (Microprose et. al, US, 1991-2016) or the Total War series (Creative Assembly, UK, 2000-2019) use the ludic component of complex game mechanics and rule systems to show why it was as it was. Not without mentioning, of course, that these classifications are extreme examples and that there are also plenty of mixed forms (see Chapman, 2016, pp. 82-120). In the following, we will examine an example each of a “realist simulation” and a “conceptual simulation” to see how players address aberrations from this authenticity paradigm, which they often seem to perceive as breaking a taboo.

Battlefield V, published in November 2018, shows how strongly authenticity is interwoven with taboos around the “right” representation of history in digital games. The first-person shooter game from the popular Battlefield series caused controversy across various social media about the “right” representation of the Second World War in digital games on the occasion of the first release of a trailer. Many users criticised that the trailer showed an apparently female British soldier who was involved in fighting German soldiers, all while using a mechanical arm. The criticism was ignited primarily by the gender of the figure and secondarily by the use of the mechanical arm. Both were – among other things – decidedly perceived as inauthentic. Especially interesting are several threads on the social media website Reddit from the day of the trailer release 3. We used CrowdTangle to find the threads with the most interactions. The big debates around Battlefield V took place mainly in the subreddits r/games and r/battlefield. Due to the ‘up and down vote’ principle of the website, it is possible to make statements about the popularity of certain posts and certain comments, although it should be noted that these can also be manipulated – for example through the use of multiple accounts and bots. For this analysis, we have examined particularly popular comments and responses i.e. the opinion leaders voicing the hegemonic positions

The most popular commentaries around the appearance online of the first trailer of the game all revolve around the representation of the Second World War which is perceived as inauthentic. While one user states, that the game “didn’t look like WW2 at all” 4 another asks: “Seriously, what the hell was that?” 5 and a third chimes in his distaste for the game: “A complete and utter bastardization of World War 2. What a disgrace” 6. These users’ criticism on Reddit mainly take aim at the following: Women as part of the fighting troops, inauthentic uniforms and weapons, a basic mood perceived as being too “colorful” and an “unrealistic” gameplay that does not do justice to the Second World War. Several users complain about a lack of respect for the veterans of the Second World War: “Remember when they revealed BF1 and were all about giving credit to those poor soldiers in WW1. Seems like the soldiers from WW2 don’t deserve that.” and: “Watching it made me feel like all the respect for anyone that served in that war was completely gone, How disrespectful can a company be?” 7.

The analysis of these individual points of criticism shows that the main complaints are focused on the fact that a British soldier, who plays a central role in the trailer, is female and, in addition, disabled: “Most immersive, authentic WWII game shows British female soldier on the frontlines with prosthetics I mean there is being PC and then there is being inaccurate. Women didn’t fight mate, certainty not frontline. That’s not “anti feminism” it’s facts” 8. “Facts” is a central keyword in this context – the commentators in the different threads repeatedly emphasize that although they have no problem with women in digital games, they wish for a “fact”ually correct portrayal of the Second World War. While some users are sarcastic and mention several times that their grandmothers were World War veterans: “My grandma is a WW2 vet. She was a sniper with a claw arm” 9, others are outraged and see the memory of their ancestors tarnished: “60 million, we lost 60 million brave souls fighting in this war, and we get a childish colorful excuse of a game from it” 10. One can clearly see from the language how the perceived breach of taboo is staged as the desecration of the fallen, i.e. as the desecration of a sacrifice for the community. The statement made by users that they have basically no problems with women in digital games seems insofar implausible because of the frequency of complaints about the female protagonist. No other point of criticism – be it the colour setting or the very fast-acting gameplay itself – is repeated with such vehemence in the comments we read as the criticism of the soldier’s gender. It is, of course, true that women in the British Army were generally not part of the fighting troops – so this depiction is factually incorrect. At the same time, however, one must be aware that digital games about the Second World War are full of “mistakes”: “Real” soldiers couldn’t respawn, couldn’t regenerate magically, couldn’t carry hundreds of kilos of equipment, didn’t have a heads-up display in front of their eyes etc. But all these things occur in Battlefield V and are necessary for the game to work – it has to be different from everyday reality (Huizinga, 1997). These obviously necessary artistic freedoms in the representation of the Second World War are accepted – and probably not even noticed – by the same players who complain so bitterly about the representation of women in their games because they have this fixed idea how the World War II really was.

Any deviation from their hegemonic narrative about the Second World War is perceived as an insult, a breaking of taboos which is therefore sanctioned by ridiculing the game. This indicates a transgenerational identification with the soldiers of the Second World War who are perceived as heroes. A free interpretation regarding the semantic scope of the “Second World War” represents a personal insult to one’s own identity and is accordingly antagonized. Critical voices that point out that Battlefield V is first and foremost a game to entertain are marginal and only become visible in the discourse if one looks for less popular comments. The hegemonic discourse in the threads studied is clearly negative towards the game and its portrayal of the World War II. Factual correctness, however, is mainly demanded with regard to the gender and the disability of the protagonist. The genre-typical factual abbreviations – war crimes, suffering of the civilian population, genocides etc. are neither mentioned in the trailer nor in the later game in any way – are accepted approvingly. Not surprisingly, the aforementioned basic differences between diegesis and extra diegesis, such as the fact that protagonists survive gunshot wounds without any problems or players being able to simplify the difficulty level of the fight by mouse-click, are not addressed at all – one-armed female snipers seem to overshadow everything. It becomes clear how strongly the perception of authenticity is linked to the visual level for these players: the game must look like they imagine the Second World War to be. For this reason, other deviations – such as incorrect weapons or uniforms – are usually also criticized, but not with the same vehemence as the depiction of women as part of the fighting troops. An interesting aspect of the discussion about the “wrong” portrayal of the Second World War in Battlefield V is that many users relate the story directly to themselves and their ancestors. Incidentally, this represents such a hegemonic fragment of discourse in the critique of the game that the game’s publisher integrated these negative comments into its own advertising campaign. Under the hashtag “#EveryonesBattlefield” they collected numerous such insults as, for example: “Did my grandfather storm the beaches of Normandy [for this] s***?” The controversy surrounding Battlefield V is part of a larger debate about representation and identity politics in digital games, which reached its early climax in the infamous “Gamergate controversy” in 2014 and 2015 (Dewey, 2014, Condis, 2018). In this context, the desire for so-called historical authenticity must be seen as a proxy argument of a larger debate around new forms of representation in digital games which have been perceived as threats by a rather small but very vocal group of gamers who use Social Media to express their anger and disdain (ibid.). Using Battlefield V in particular as an example, the players take any deviation from the hegemonic narrative of the correct and authentic depiction of the Second World War as a breach of taboo and react accordingly: with criticism, insults, and ridicule.

While the debate around Battlefield V was mainly ignited by the – from the recipients’ perspective – misrepresentation of the Second World War, which was perceived as “inauthentic”, the pendulum in the debate on authenticity around the game Hearts of Iron 4 (see above) swings in exactly the opposite direction. Having already addressed the question of how National Socialist symbols, the Holocaust and other crimes of war are depicted in the popular World War II game, we now want to look at how the players themselves react to these exclusions in the game’s presentation. We examined representative statements of players in relevant forums in the form of a qualitative discourse analysis and identified the hegemonic accepted statements. To this end, we systematically searched relevant forums for the thematization of our central analysis category “Holocaust” (also for synonyms such as “Shoah” or related categories such as “war crimes” or “crimes against humanity”) and qualitatively evaluated the debates taking place there using the method of critical discourse analysis (Wodak et al, 2009, Jäger, 2011).

There are numerous threads on both the gaming platform Steam and Reddit in which, for example, the absence of the Holocaust and other war crimes are addressed. In the forum of the game developer Paradox itself, threads dealing with the Holocaust are explicitly forbidden and will be closed by the mods almost immediately. This is justified as follows: “There will not be any gulags or deathcamps (including POW camps) to build in Hearts of Iron 4, nor will there be the ability to simulate the Holocaust or systematic purges, so I ask you not to discuss these topics as they are not related to this game. Thank You. Threads bringing up will be closed without discussion” 11. The forum rules also prohibit threads on swastikas, area bombing and all other topics of political significance. Already at this point we can thus see that a taboo is in place for certain controversial topics and is, in this case, perpetuated by the developer.

The discussions on the platform Reddit on this topic are better-mannered and of higher quality than on Steam. This is probably due to a much stricter moderation, on the one hand, and because of the rating system of the comments, on the other. On the Steam forums, for example, comments that openly deny the existence of the Holocaust are not deleted 12. On reddit, “troll” comments are either deleted immediately or are not visible due to their negative rating.

A recurring misconception in both forums, however, is the widespread assumption that the depiction of the Holocaust in digital games in of itself would violate German law, which is not the case. On the contrary. The taboo attached to depicting the crimes of the Nazi state is doubled, in that many of the people posting in the different forums perceive a portrayal of the Holocaust in a digital game as a violation of a social taboo that would be punished. The concerns range from a ‘shitstorm’ that would be whipped up against the game to a complete ban: “the SJW’s don’t care how it’s portrayed, they see the word holocaust and go beserk“ 13 And: “if they put the holocaust in and other things like that then it’d get banned in a lot more countries“ 14.

More interesting, however, is the recurring argument that Hearts of Iron IV is a strategic war game and that the crimes that the various warring parties committed against the civilian population, above all, the Holocaust, would not be part of the war: “There’s no need for that. HOI is a military strategy game, no simulator or something” 15. In this argumentation, there is often a conscious, sometimes unconscious blurring of two different levels. On the one hand, the suffering of the civilian population and the crimes against them are separated from the apparent warfare, on the other hand, these crimes are also seen as detached from the fighting troops: “Adds nothing to gameplay and remember, at the end of the day this is a game. Further, it’s a war game, generals like Rommel were tasked with defending beaches and capturing cities, not doing a politician’s job of fixing political dissidents and interning them” 16. The response to the question of whether the Holocaust should be portrayed in Hearts of Iron IV is problematic in several respects. First of all, the user implies that the victims of the Shoah are “political dissidents” – this is of course as wrong as it is dangerous. The European Jews were murdered by the Nazis because they were Jews and not because they held different political positions. (Aly, 1998; Friedländer, 2007, 1997) At the same time, it also perpetuates the myth of the “clean Wehrmacht” (Chapman & Lindenroth, 2015; Pfister, 2020). “Generals, like Rommel” were of course involved in the crimes of the Nazi state, the Wehrmacht was part of the apparatus of annihilation (Wette, 2007). Among those who oppose a depiction of the Holocaust in Hearts of Iron, this is a recurrent narrative, which, as mentioned earlier in this article, is part of a long tradition of debates in the successor societies of the Nazi state itself: The war and the fighting troops are seen as detached from the crimes of the National Socialists. The Holocaust is thus wrongly reduced in these games to the actions of a small circle of psychopaths i.e. the elite of the “Third Reich”.

There are however also commentators on these forums who advocate an integration of civilian casualties in games: “Honestly, I wished it took into consideration civil casualties. About 3% of the world’s civilians died in that war. That’s about 60 million and that’s no [sic] including Japanese expansion into China in 1933-1939. Now, I’m not talking about adding the Holocaust. Honestly, I think they should shy away from that” 17. Most of them agree, however, that this should not happen on a ludic level, but that the players should be informed about war crimes by events, notifications, counters and info-boxes. A recurring fragment of the discourse is that the goal is to communicate how horrific the Second World War was and what a high price the civilian population, in particular, had to pay.

It is evident here how strongly the representation of the Holocaust in digital games is seen as taboo, not least on the part of the players themselves. Even those who wish for a more nuanced depiction of the Second World War, which openly addresses the historically unique destruction of human life, shy away from including the Holocaust, even as pure information on the narrative level of the game. The reasoning behind this, however, is not so much of a moral nature, i.e. that the horror of the Holocaust in of itself would forbid it from ever being portrayed in a game, but the external effect of such a portrayal: “Holocaust I think not… Just imagine the PR shitstorm” 18. The debates about the possibilities of depicting the Holocaust, which have already been discussed in detail in this article, are thus also repeated in the reception of the digital games themselves: What can be shown and what not? The question of how it can be possible to depict the crimes of the Second World War after the fact in digital games is indeed a difficult one. However, as our analysis shows, the complete absence of these atrocities is not an adequate solution either. After all, it perpetuates historical revisionist myths such as that of the “clean Wehrmacht” and disregards central aspects of World War II. Simultaneously, we can also detect a certain need of the players to keep their games free from the horrors of the systematic crimes against humanity that were committed during this period. The taboo of depicting the Holocaust in digital games thus serves to protect a romanticized notion of the Second World War which reduces it to only the strategic warfare of the battlefield.

Conclusion

In general usage, the term “taboo” is increasingly perceived from a critical standpoint and viewed as something negative. After all, taboos appear conservative, out-dated, and authoritarian: They create a climate in which it is prohibited to speak, to act, or even to think about a certain topic. From this understanding, taboos do not allow for discussion and thus, it can be argued, block change. As we were able to show with our analysis, this is partly true and indeed problematic with regard to digital games. While the origin of the taboos examined here are morally understandable, the extreme restrictive interpretation of German law, for example, did not lead to a critical portrayal of the Nazi regime but rather to its depoliticization. As a result, taboos already consensually broken by society as a whole, such as mentioning the participation of the regular German army in the crimes of the Nazi state, were suddenly reinstated in the games.

The taboo of the Shoah’s irrepresentability is a different matter and one must rightly ask if digital games could ever be the right medium to portray the Holocaust. While an answer to this question goes behind the scope of this article, we must keep in mind that it was the survivors of the Shoah, but above all their descendants, who sought new ways to report on this historical experience. One after the other, taboos surrounding what can be said or shown in regard to the Holocaust have been broken. To a certain extent, it is understandable that digital games, as the most recent medium, are following the examples set by the novel, the film and the graphic novel. Of course, it is hard to imagine how the Holocaust could ever become part of a game that aims to entertain. However, we have shown that exactly the same accusation was levelled at the feature film more than twenty years ago. Games such as Wolfenstein: The New Order, Call of Duty WW II and Through the Darkest of Times have shown what a responsible approach to the memory of Nazi crimes in games could look like in the future.

The breaking of taboos is a particularly important sign for historians of social and political change. That this discursive change does not only come from above, but also from below – it was first discussed in forums before politics reacted – is in a certain sense also a sign of a functioning civil society. For different functional elites are traditionally rather sluggish when it comes to shifts in hegemonic discourses, which often happen through grassroots movements in a constant process of renegotiation from below. The individual examples we have shown do not give us enough information about the extent of this discursive change. They are not sufficient in scope to clarify satisfactorily the exact reasons for the paradigm shift we have identified. But they permit us a first glimpse at different discursive statements. It also gives us insight into the darker side of a so-called gamer community, whose latent misogyny produces new forms of taboos. But here, too, it should be remembered that isolated examples once again offer no conclusion about the diffusion of this thinking.

Finally we must not forget one thing: Taboos are a central component of functioning communities and in themselves are neither morally good nor bad. By clearly marking borders that must not be crossed, they make our coexistence possible. For example, the incest taboo is an almost universal one that can be found in practically all societies for good reasons. (Lévi-Strauss, 1981) We have internalised most taboos in such a way that we no longer even notice them in our everyday lives. The constant change of taboos is also a sign of healthy communities. If, for example, the over-sexualised portrayal of women and/or racist portrayals of certain ethnic groups in games becomes a taboo in the future, this is not a sign of repression but only of a discursive change, just as we can speak openly about sexuality today thanks to the removal of taboos on sexuality in the late 1960s.

References

Aly, G. (1998). „Endlösung“. Völkerverschiebung und der Mord an den europäischen Juden. Frankfurt: Fischer-Taschenbuch-Verlag.

Benz, W. (1996). KZ-Manager im Kinderzimmer. Rechtsextreme Computerspiele, in: W. Benz (Ed.), Rechtsextremismus in Deutschland. Voraussetzungen, Zusammenhänge, Wirkungen, pp. 219-227, Frankfurt am Main: Fischer.

Bundesanzeiger (2014) Bekanntmachung Nr. 6/2014 retrieved from: https://www.bundesanzeiger.de/pub/publication/YkQsSxY1gMez55KKCBa;wwwsid=BBDB62D899EFAD15E751FC3E25B5EA14.web06-pub?0

Cauvin,. T. (2016). Public History. A Textbook of Practice. New York: Routledge.

Celeda, C. (2015) Geschichtsdarstellung in Videospielen. Darstellung und Inszenierung des Zweiten Weltkrieges im digitalen Spiel, Diplomarbeit Universität Wien, Wien.

Chapman, A. Condis, M. (2018). Gaming masculinity: Trolls, fake geeks, and the gendered battle for online culture. Iowa City: University of Iowa Press.

Classen, C. (2009). Balanced Truth: Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List among History, Memory, and Popular Culture, in: History and Theory 47, pp. 77–102.

Dankert, B. & Sümmermann, P. (2018). Hakenkreuze in Filmen und Computerspielen Entwicklungen und aktuelle Debatten zum Umgang mit verfassungsfeindlichen Kennzeichen, in: BPJM-Aktuell 2/2018, retrieved from: https://www.bundespruefstelle.de/blob/130174/3487010270e47902e1ccf9d1406b2591/201802-hakenkreuze-in-filmen-data.pdf

Dewey, C. (2014). The only guide to Gamergate you will ever need to read. The Intersect. The Washington Post. Retrieved from https://www.washingtonpost.com/news/the-intersect/wp/2014/10/14/the-only-guide-to-gamergate-youwill-ever-need-to-read/?noredirect=on&utm_term=.53b2ab0d6458

Deutscher Gewerkschaftsbund [=DGB] (2018), Keine Hakenkreuze in Computerspielen!,20.08.2018, retrieved from: https://www.dgb.de/themen/++co++cbd07522-a456-11e8-a2e4-52540088cada

Foucault, M. (2013). The Archaeology of Knowledge. London/New York: Routledge Classics.

Giffey, F. (2018). Facebook post from August 23, 2018, retrieved from: https://www.facebook.com/franziska.giffey/posts/1444702818999922/

Hartmann, C. Hürter, J. Jureit, U. Hamburger Institut für Sozialforschung (Eds..) (2005). Verbrechen der Wehrmacht: Bilanz einer Debatte. München: Beck.

Friedländer, S. (1997). Nazi Germany and the Jews: The Years of Persecution 1933–1939. New York: Harper Collins.

Friedländer, Saul (2007). The Years of Extermination: Nazi Germany and the Jews 1939–1945. New York: Harper Perennial.

Hansen, M. (1996). “Schindler’s List” is not “Shoah”: The Second Commandement, Popular Modernism, and Public Memory, in: Critical Inquiry 22, no. 2, pp. 292–312.

Jäger, S. Diskurs und Wissen, in: Reiner Keller et al, Handbuch Sozialwissenschaftlicher Diskursanalyse. Band 1. Wiesbaden: Springer, pp. 91-124.

Krieghofer, Gerald. 2017. „‘… nach Auschwitz ein Gedicht zu schreiben, ist barbarisch …’ Theodor W. Adorno”. In: Zitatforschung, 20.11.2017. retrieved from: https://falschzitate.blogspot.com/

2017/11/nach-auschwitz-ein-gedicht-zu-schreiben.html?m=0

Lévi-Strauss, C. (1981) Die elementaren Strukturen der Verwandtschaft. [Paris 1948] Frankfurt/M.: Suhrkamp.

Hoffman, J. (2014). Major New Game Set at Nazi Concentration Camp Is Top Seller, in: Times of Israel, 17.06.2014. retrieved from: www.timesofisrael.com/major-new-game-set-at-nazi-concentration-camp-is-top-seller

Küveler, J. (2017). Ein Nazi ist ein Nazi ist ein Nazi, in: Welt 04.12.2017, retrieved from: https://www.welt.de/kultur/article171238125/Ein-Nazi-ist-ein-Nazi-ist-ein-Nazi.html

Lietzmann, Sabina. 1979. „Die Judenvernichtung als Seifenoper”. In: Märthesheimer, Peter; Frenzel, Ivo (Hrsg.) Im Kreuzfeuer: Holocaust. Eine Nation ist betroffen. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, S. 35–39.

Lindemann (2014) https://www.faz.net/aktuell/feuilleton/debatten/der-egoshooter-wolfenstein-the-new-order-13029821-p2.html

Lindner, B. (1998). Was heißt: Nach Auschwitz? Adornos Datum, in: S, Braese et al. (Ed.): Deutsche Nachkriegsliteratur und der Holocaust, pp. 283-300, Campus Verlag: Frankfurt / New York.

McWerthor, M. (2010). Concentration Camp Game Was Meant To Be ‘Fun’, in: Kotaku, 12.10.2010, retrieved from: https://kotaku.com/concentration-camp-game-was-meant-to-be-fun-5711317

Meier, S. (2020). Sid Meier’s Memoir!, W.W. Norton & Company: New York

“Mit Hakenkreuzen spielt man nicht”, in: Frankfurter Allgemeine 23.08.2018, retrieved from: https://www.faz.net/aktuell/wirtschaft/digitec/franziska-giffey-kritisiert-hakenkreuze-in-computerspielen-15751700.html

Munslow, A. (2007). Deconstructing History, New York: Routledge.

Niethammer, L. (1990). Juden und Russen im Gedächtnis der Deutschen, in: W. H. Pehle (Ed.), Der historische Ort des Nationalsozialismus (pp. 114 – 134), Frankfurt/Main: Suhrkamp.

Parker, L.A. (2016, August 31). Inside Controversial Game That’s Tackling the Holocaust. Retrieved from https://www.rollingstone.com/culture/culture-news/inside-controversial-game-thats-tackling-the-holocaust-251102/.

Pfister, E. (2018). “Of Monster and Men” – Shoah in Digital Games, in: Public History Weekly. Retrieved from https://public-history-weekly.degruyter.com/6-2018-23/shoah-in-digital-games/

Pfister, E. (2019). ‘Man spielt nicht mit Hakenkreuzen!’ Imaginations of the Holocaust and Crimes Against Humanity During World War II in Digital Games, in: A. von Lünen et al. (Eds.), Historia Ludens: The Playing Historian, pp. 267-284, London: Routledge.

Pfister, E. (2020). Why History in Digital Games Matters. Historical Authenticity as a Language for Ideological Myths. In: M .Lorber, M. & F. Zimmermann (Eds.), History in Games. Contingencies of an Authentic Past. Transcript: Bielefeld.

Reckwitz, A. (2017). Die Gesellschaft der Singularitäten. Zum Strukturwandel der Moderne. Berlin: Suhrkamp.

Robertson (2017). Watching internet Nazis get mad at Wolfenstein II is sadder than the game’s actual dystopia, in: The Verge, retrieved from: https://www.theverge.com/2017/6/12/15780596/wolfenstein-2-the-new-colossus-alt-right-nazi-outrage

Sabrow, M. (2009). Den Zweiten Weltkrieg erinnern. in: ApuZ 36–37/2009.

Samida, S. (2014). Kommentar: Public History als Historische Kulturwissenschaft: Ein Plädoyer, in: Docupedia-Zeitgeschichte, 17.06.2014 DOI: http://dx.doi.org/10.14765/zzf.dok.2.575.v1

Schiffer, C. (2017). Wie ein Computerspiel deutsche Geschichte entsorgt, in: Deutschlandfunk, 09.11.2017, retrieved from: https://www.deutschlandfunk.de/wolfenstein-2-wie-ein-computerspiel-deutsche-geschichte.807.de.html?dram:article_id=400222#:~:text=Die%20Juden%20in%20der%20deutschen,Nationalsozialisten%20und%20marginalisiert%20alles%20j%C3%BCdische.

Schröder, H./Mildenberger, F. (2012). Tabu, Tabuvorwurf und Tabubruch im politischen Diskurs. In: ApuZ 5-6/2012.

Schwart, A. (2010). Computerspiele – Ein Thema für die Geschichtswissenschaft?, in: A. Schwarz (Ed.), “Wollten Sie auch immer schon einmal pestverseuchte Kühe auf Ihre Gegner werfen?” Eine fachwissenschaftliche Annäherung an Geschichte im Computerspiel, pp. 7-28, Lit Verlag: Münster.

Sridhar, P. (2008). No Game about Nazis for Nintendo, in: The New York Times, 10.03.2008, retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/2008/03/10/technology/10nintendo.html

Steuer, M. (2017). The (Non)Political Taboo: Why Democracies Ban Holocaust

Denial, in: Sociológia 2017, Vol. 49 No. 6, pp. 673-693.

Tschiggerl, M., Walach T. & Zahlmann, S. (2019). Geschichtstheorie. Wiesbaden: Springer.

Wette, W. (2007). The Wehrmacht: History, Myth, Reality. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Wiesel, Elie. 1979. „Die Trivialisierung des Holocaust”. In: Märthesheimer, Peter; Frenzel, Ivo (Hrsg.) Im Kreuzfeuer: Holocaust. Eine Nation ist betroffen. Frankfurt am Main: Fischer, S. 25–30.

Tschiggerl, M. (2020). Die Hyperrealität des Videospiels. In S. Zahlmann (Eds.), Die Wirklichkeit der Steine 4. Wien: Peter Lang. (forthcoming)

Trips-Hebert, R. (2014), Das strafbare Verwenden von Kennzeichen verfassungswidriger

Organisationen, in: Deutscher Bundestag Infobrief WD 7 – 3010 – 028/14, retrieved from: https://www.bundestag.de/resource/blob/195550/4db1151061f691ac9a8be2d9b60210ac/das_strafbare_verwenden_von_kennzeichen_verfassungswidriger_organisationen-data.pdf

Video Game discovered uses Nazi Death Camps as Theme, in: New York Times, May, 1 1991, retrieved from: https://www.nytimes.com/1991/05/01/world/video-game-uncovered-in-europe-uses-nazi-death-camps-as-theme.html

Waxman, O. (2020). Video Games May Be Key to Keeping World War II Memory Alive. Here Are 5 WWII Games Worth Playing, According to a Historian, in: Time 27.08.2020, retrieved from: https://time.com/5875721/world-war-ii-video-games/

White, H. (1973) Metahistory: The Historical Imagination in Nineteenth-Century Europe. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. 1973

Wodak R. et al. (2009). The Discursive Construction of National Identity. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

Ludography

Assassin’s Creed – series, Ubisoft et al, France, 2007-2018

Attentat 1942, Charles Games, Czech Republic, 2017

Battlefield V, DICE, EA, Sweden, USA, 2018

Call of Duty – series, Infinity Ward et al., USA, 2003-2019

Call of Duty: World at War, Treyarch, EA, USA, 2017

Call of Duty: WWII, Sledgehammer Games, Activision, USA, 2017

Hearts of Iron IV, Paradox, Sweden, 2016

Indiana Jones and the Last Crusade, Lucasfilm Games, USA, 1989

KZ Manager, unknown developer, Austria, unknown date

Medal of Honor – series, Dreamworks Interactive et al., USA, 1999-2012

Panzer General, SSI, USA, 1994

Sid Meier’s Civilization – series, Microprose et al., US, 1991-2016

Sonderkommando Revolt, Maxim Genis, Israel, 2010

Through the Darkest of Times, Paintbucket Games, Germany, 2020

Total War – series, Creative Assembly, UK, 2000-2019

Valkyria Chronicles, Sega, Japan, 2008

Wolfenstein 3D, id Software, USA, 1992

Wolfenstein: The New Order, MachineGames, Bethesda, Sweden, Usa, 2014

Filmography

Holocaust – TV series, Marvin J. Chomsky, USA, 1978

Inglorious Basterds, Quentin Tarantino, USA, 2009

Iron Sky, Timo Vuorensola, Germany, Finland, Australia, 2012

Overlord, Julius Avery, USA, 2018

Schindler’s List, Steven Spielberg, USA, 1993

Shoah, Claude Lanzmann, France, 1985

Authors’ Info:

Eugen Pfister

Hochschule der Künste Bern – HKB

Martin Tschiggerl

Universität des Saarlandes

martisch.tschiggerl@uni-saarland.de

- The title’s quote is from https://www.dailymail.co.uk/sciencetech/article-6095213/Uncensored-swastikas-allowed-video-game-time-20-years-Germany.html ▲

- https://steamcommunity.com/app/394360/discussions/0/1621724915820727618/. ▲

- Thread: “BFV I’m just going to say it…” posted on Reddit on 23.05.2018 by the user “unofficalmoderator”. Online: https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/ last accesed on 17.7.2020 ▲

- Ibid. user “stesser” https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgqdzy ▲

- Ibid. user “CheesySombrero” https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgq354 ▲

- Ibid. unknown user (user has since deleted his account) https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgr08m ▲

- Ibid. ▲

- Ibid. user “PenPaperShotgun” https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgr4zb ▲

- Ibid. user “st4rgasm” https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgr3rj ▲

- Ibid. user “Reactiveisland5” https://www.reddit.com/r/Battlefield/comments/8lmnrn/bfv_im_just_going_to_say_it/dzgqv4w ▲

- Thread “*** HOI IV Forum Rules – Read Before You Post ***” posted on Paradox Forum on 08.08.215 by user “Secret Master”. online: https://forum.paradoxplaza.com/forum/threads/hoi-iv-forum-rules-read-before-you-post.875352/ last accesed 17.07.2020. ▲

- user “God Failed Me” in the Thread: “The holocaust etc“, posted by the user “NemoNobody” on the Hearts of Iron IV Form und Steam on 10.06.2018 https://steamcommunity.com/app/394360/discussions/0/1697175413681651071/#c1697175413683043772 last accessed 17.7.2020 ▲

- Ibid. user “MikeY” https://steamcommunity.com/app/394360/discussions/0/1697175413681651071/#c1697175413682101085 ▲

- Ibid. https://steamcommunity.com/app/394360/discussions/0/1697175413681651071/#c1697175413681654327 ▲

- user “hoi4commander” in the Thread: “Do you think that HOI4 should portray the darker parts of World War II?”, posted by the user “ImperatorBevo” on the r/HOI4 und Reddit on 06.12.2016 https://www.reddit.com/r/hoi4/comments/5gpjz0/do_you_think_that_hoi4_should_portray_the_darker/dauj6uy/ last accessed 17.7.2020 ▲

- user “NotaInfiltrator” in the Thread: “Discussion; Should Holocaust be in the game?”, posted by the user “AlphaBravoLima” on the r/HOI4 und Reddit on 04.05.2017 https://www.reddit.com/r/hoi4/comments/696gp8/discussion_should_holocaust_be_in_the_game/dh48mtd/ last accessed 17.7.2020 ▲

- user “NotaInfiltrator” in ““Do you think that HOI4 should portray the darker parts of World War II?” “https://www.reddit.com/r/hoi4/comments/5gpjz0/do_you_think_that_hoi4_should_portray_the_darker/dau8982 ▲

- Ibid. user “the_bolshevik” https://www.reddit.com/r/hoi4/comments/5gpjz0/do_you_think_that_hoi4_should_portray_the_darker/daubw1m ▲

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.