PDF Download

PDF Download

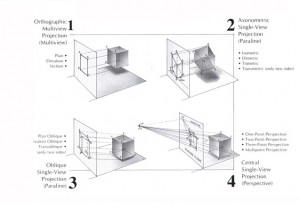

Despite the dominant view that distinguishes video game space from other spatial representations as navigable space, someone who engages with the screen space of a video game must first and foremost rest at an ideal viewing spot in physical space, which is in accord with the requirements of a proper screening. In other words, one’s illusory experience of navigable space becomes possible only if one’s body in physical space occupies the visual center on which the scenographic arrangement relies in order to function. This type of “spectatorship” (Florenski, 2001, p. 57) 67, which is also central to the form of video games (Rehak, 2003, p. 118), has a long tradition in western mimesis and can be traced back to ancient theatre, in which the visual order relied on principles of Euclidian geometry. Revived during the Renaissance, and further developed with the notion of Cartesian space, this mode of representation, together with its implied spectator position, became the way of seeing in the New Age, and continues today, where it now serves as the basis for graphic rendering technologies in computer-generated imagery, animation, and video games (Taylor, 2003; Graça, 2006, p. 4; Wells, 2006, p. 1).

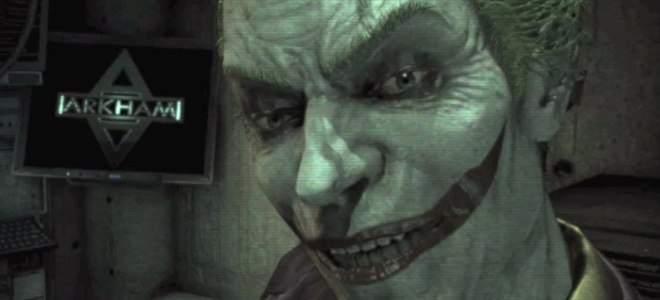

At the heart of this tradition lies linear perspective, a practice of representation that asks the spectator to remain immobile in front of a stage, and to have a fastened eye that sees what is brought to its sight (Florenski, 2001, p. 57). Based on a strong faith in natural sciences that were instrumental in its development, linear perspective is often hailed as the most “naturalistic” and “scientific” method to be used in the visual representation of the world. Rooted in Plato’s philosophy, which is known for the “prominence [it] bestows on visual activity, considered to be equal to cognitive activity” (Stoichita, 1997, p. 22), this mode of representation is also believed to reveal the truth (the capacity to reach the “inside”) while remaining objective (the capacity of stating the factual from “outside”), a highly problematic duality that has been the subject of much debate in anthropology, especially in the distinction between the emic (insider) and the etic (outsider) positions in anthropological field research (Harris & Park, 1983, pp. 10-11), and in photography theory, where the status of documentary photography in particular has been strongly questioned with regard to truth and objectivity (La Grange, 2005). The naturalistic effect that can be achieved in this mode of representation is specifically related to its success in self-effacement; that is, its success in managing to render its own form invisible and, through this, its capacity to function as an “engine of affirmation” (Kolker, 1992). Showing similarities to the notion of continuity in cinema, game genres like the first-person shooter have been praised for exactly this kind of fluent, realistic and seamless “direct representation” in which “looking and targeting come together, and the player [is] invited to follow his gun” (Kleijver, cited by Hitchens, 2011). Put in Ryan’s (2001a) words, “we experience what is made of information as material” (p. 68). This illusion provides enough ground to be able to state that screen spaces such as interfaces “are ideological, they work to remove themselves from awareness, seeking transparency—or at least inobtrusiveness—as they channel agency into new forms” (Rehak, 2003, p. 122). Lefebvre (1991) also points out this relation of spatial representation to ideology: “What is an ideology without a space to which it refers, a space which it describes, whose vocabulary and links it makes use of, and whose code it embodies?” (p. 40).

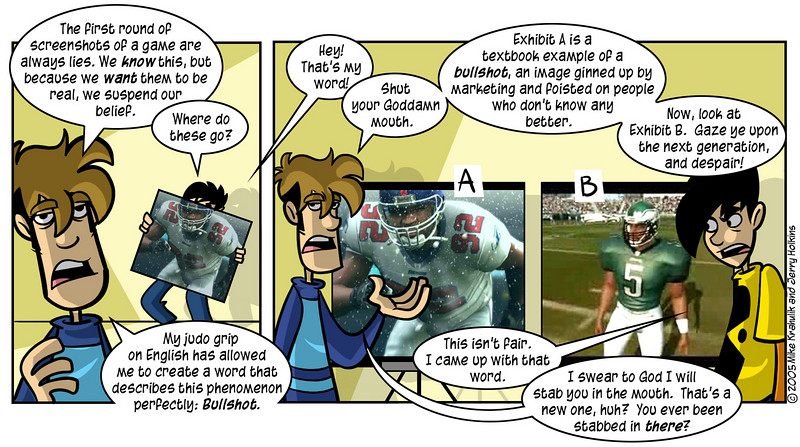

As Taylor (2002) has pointed out, “the dominance of linear perspective as a mode of representation has been much interrogated for other forms of pictorial representation, [but] it has not been so for video games” (p. 2). Taylor (2003) further states that “much of the current critical and theoretical literature on new media, including video and computer games, assumes both the conceptual transparency of the video or computer screen and the absolute authority of a rational scientific order.” As a result of these assumptions, developers, researchers and players alike tend to equate the underlying models of Euclidean geometry and Cartesian space to real space, and assign images rendered through methods of linear perspective to the status of the tangible, a quality which is often expressed through the terms “realistic” and “navigable.” In game development practice, this means that “video games have given implicit priority to unified monocular vision” (Taylor, 2002, p. 2) and that it is a widespread “assum[ption] that the screen is transparent and the player can effectively merge with the game space” (p. 12). However, as an observation of Rehak (2003) clearly reveals, these assumptions of transparency and the player’s effective merging with screen space remain problematic: “to sit at a computer and handle mouse and keyboard is to be physically positioned; to misrecognize oneself as the addressee of the screen’s discourse is to be interpellated as a subject” (p. 122). Not only the construction of screen space, but also the construction of the broader “stage” in which spectatorship takes place must be therefore regarded as instrumental in “enabling a snug fit between the player and his or her game-produced subjectivity” (Rehak, 2003, p. 119). As Martin Heidegger has observed, the world becoming an image is the same as the human being becoming a subject (cited in Sayın, 2001, p. 15). Hence, “producing a coherent space of reception for a viewing subject” is at the same time the “construction of unified subject positions” (Rehak, 2003, p. 119).

Rehak’s observations not only capture the mobility/immobility and inside/outside dualities, both of which are central to this model of video game consumption, but they also point into the theoretical direction of psychoanalysis. As Taylor (2003) has pointed out, “the models of subjectivity and agency offered by psychoanalysis provide a way to investigate the relationship of player, player-character and the screen [and to] examine how perspective shapes the field of gaze and the implications of the shaping.” Most importantly, Lacanian subject theory has shown that the production of spatial representation and the production of subject is an inseparable moment. This notion of simultaneity is a strong point of departure for reconsidering the abovementioned dualities in our perception of gaming both as players and as game researchers. However, dealing with this topic also requires taking a closer look at the concept of linear perspective as it has been questioned and criticized in architecture, the fine arts, and screen theory. In these fields, we find a number of works that give a critical account of linear perspective, among them studies on inverse perspective which deserve special attention.

The Inversal of Perspective: Gaze, Space and the Subject

Inverse perspective does not simply refer to a visual style whose most impressive examples were produced during the era of the Byzantine Empire, but it must also be regarded as a conceptual tool in the arsenal of modern art criticism, one that has been used to capture the immersive relationship between a work of art and the looking object, and the aesthetic experience that results from this encounter. Thus, the notion of inverse perspective plays a twofold role in understanding the relationship between the visual construction of ludic spaces and the production of ludic subjects. Firstly, it serves as a radical point of departure to critically approach the philosophies behind the representational strategies applied in contemporary gaming technologies and the mode of consumption that is fostered thereby. On the other hand, it serves as a metaphor that powerfully describes the immersive experience of “being at play” (in lusio, illusion), and allows us to relate to Lacanian psychoanalysis, whose theoretical framework has identified several (some of them spatial) misrecognitions (or inversals) that play a role in the production of subjects. Both Lacanian subject theory and the notion of inverse perspective have many common points that are helpful in the interrogation of linear perspective and the type of spectator/subject that it produces. These common points are particularly useful for overcoming the abovementioned dualities, which seems to hamper the attempts to formulate a theory that gives a more accurate account of a player’s relation to on-screen representations and/or social spaces.

Linear perspective’s claims in regard to naturalism have long been under dispute in other arts. This “wordview” has also been criticized for standing in association with the Cartesian cogito, which provides the basis for a subject theory that projects the human as a conscious being guided by reason as it “acts upon” an external world made tangible through the objectively truth-revealing powers of the natural sciences. To its critics, linear perspective is imperialistic (just as the modern rational subject whose “eye” it represents), its goal is “to tame the world, to take it under the control of a notion of space that can be ordered, looked at, invaded and possessed” (Florenski, 2001, p. 57). Rather than being copies identical to the real world, images created based on this method need to be considered as “the result of a complex calculation and coding process” (Graça, 2006, p. 3), of “a mechanical, automated eye” (Florenski, 2001, p. 57) which can render through its schematic order any sight into image, while treating them with equal indifference. Thus it is considered to be a process which cannot simply be regarded as an accurate reproduction of the way the human eye sees, for it lacks a human touch in the first place, but it must be seen as a visual discourse that is the product of a particular moment in history. The claim of representing the world as humans see it, comes even more under dispute when one considers the non-photographic nature of video and computer games, that is, their use of virtual cameras whose “animated camera movements are generated frame by frame imitating their cinematographic equivalents” (Hernandez, 2007, p. 38), a fact which is also indicative of the presence of “an autonomous universe, unfastened from factual existence” (p. 38). However, even if it were a photographic reproduction of the real world rather than a completely invented universe , the artificiality of such realistic rendering would still prevail. This is a fact which, according to Graça (2006), is largely ignored: “scholars deem to disregard that photographed pictures are graphical constructs that can be, and are, used to deceive” (p. 2). Graça continues by stating that “each photographed picture is already the result of a calculation process and, in its very essence, is not the expression of a physical direct human experience of time and space, but rather a visualization” (p. 4). Hence, “it does not correspond to a neutral process of ‘copying’ physical reality but, instead, is a process of building virtual representations according to a set of precise mathematical rules” (p. 4). Florenski (2001), not only critical of, but also strictly opposed to linear perspective, draws attention to the fact that some devices used in linear perspective drawing do not even require the artist to have an eye, since the artist can construct images without looking at the objects he draws (pp. 105 and 109). This level of mechanization and automation, the separation of hand from eye, and of creativity from realization, seems to stand in stark contrast with artistic views that strive to avoid “becom[ing] part of the production line as a functionary of the technical scheme within the apparatus” (Graça, 2006, p.6) and are against the extensive use of a “technical mechanisms standing between conception and finished work” (p. 5).

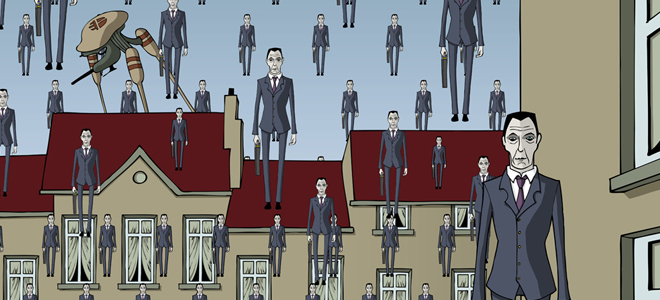

Opposed to the alienation of the artist from his work, inverse perspective is a term that has not only been used to emphasize integrity between artist and artifact, body and soul, human and nature, but also between artwork and spectator. In regard to aesthetic experience, this notion starts by suggesting that the viewer is positioned at the vantage point of the gaze of another. This vantage point, which is implied by the visual structure of the artwork itself, intersects with the viewing spot in front of the picture frame (or screen) that the spectator occupies. Through this implied position within the field of gaze, the spectator finds itself as part of extended screen space (Zettl: 1990, p. 134). When the spectator activates the codes of the work, it finds itself “inside and outside of the object at the same time” (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 13) in an “encompassing field of seeing” (Taylor, 2003) and experiences itself “engaged in reverse perspective, in his/her self-image” (Pallasmaa, 2005, p. 12). In other words, it is not only the image that is exposed to the spectator here, but also the spectator who is exposed to the image: the goal of representation is not simply to give the spectator access to the virtual world, but also to give the virtual world access to the spectator. (Sayın, 2001, p. 16).

Pallasmaa (2005, p. 40) feels the need to refer to psychoanalysis to capture this immersive relationship with space and spatial representations by claiming that there is no body without a place in space, and no space which is not related to the unconscious image of the perceiving self, a connection that is central in the context of our interrogation. According to Taylor (2003), this is due to the gaze dominating the relationship because it is the very structure of this relationship. This is a structure that, according to Clemens (1996), “contradicts logic, for rather than the model preceeding its image, the image preceedes its putative model, that is, the body” (p. 74). It has been attempted more than once to describe this experience of “the looking back of the subject onto itself” (Taylor, 2003) with the metaphor of (divine) light. For example Byzantine icons are said to “take into their light the eye that looks at them (…) the light rays do not run from the eye to the image, but from the image to the eye” (Sayın, 2001, p. 16). Interestingly, Lacan too speaks of such light when he describes gaze: “it looked at me at the level of the point of light, the point at which everything that looks at me is simulated”. He continues to explain this experience of inverse raytracing as “the reduction of the subject to object in the field of gaze” (cited by Taylor, 2003).

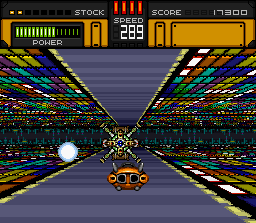

While the notion of inverse perspective seems to put forward a quite unified vision in regard to aesthetic experience, one in which the spectator and the artefact become inseparable, in game studies the inside/out duality remains an important figure in attempts to capture the relationship between player, avatar and screen space. Game researchers often maintain a distinction between an outsider position that acts “upon” the world and an insider position that acts “within” the world, or they put a player’s relationship to game space as a half inside/half outside position: “one is in the world, but not of the world” (Aarseth, 2001, p. 5). The problem is often put as one of directness or indirectness; for example the FPS genre is regarded as enabling “direct agency,” whereas other genres, such as the so-called god game, are regarded as involving the player “indirectly.” Classifications of game space and player point-of-view (for example Ryan, 2001b; and Aarseth, Smedstad and Sunnana, 2003) are also marked by this duality, where camera distance and angle are regarded as measures of insiderness or outsiderness. Further related to this duality is the notion of embodiment, in which, depending on whether the player is associated to an in-game representation (for example an avatar) or not, the player is regarded as “disembodied” and therefore outside because of no “corresponding pair of eyes” in the game space (Poole, cited by Taylor, 2003). Finally, there is a form of this inside/out duality which perceives the player’s relation to game space similar to a rite of passage, in which the player is thought of as an outsider who has to work his way through the interface in order to enter the game and turn into an insider. Here, the interface is regarded as both physical (part of the real world, faced externally, and screening out the player) and virtual (an envelope that wraps and contains the fictional world and the player). The inside/outside duality seems to be a major obstacle in capturing the experience of being at play, which is immersive and unified regardless of point-of-view, that is, the distance to and angle from which one perceives events and other existents, and regardless of the impossibilities that the representations suggest as being true. All these indicate that it is a pivotal task to formulate an approach that goes beyond the inside/outside duality and explains that rather than a move from outside in, both space and subject are brought simultaneously into existence within the field of gaze.

Suture and the Production of Subject and Space in the Field of Gaze

A key concept that proves to be helpful here is suture, a condition “by which spectators are ‘stitched into’ the signifying chain through edits that articulate a plentitude of observed space to an observing character” (Rehak, 2003, p. 122). Rehak (2003) cites Silverman saying that “the operation of suture is successful at the moment the viewing subject says ‘Yes, that’s me’ or ‘That’s what I see’.” (p. 122). We know from our own gaming experiences that, regardless of point-of-view, presence or absence of avatarial in-game representation, and the degree of manipulation of the game world that is allowed to the player, we said “Yes, that’s me” and “That’s what I see” many times, on the broadest imaginable palette of games from all genres, and throughout an inexhaustive variety of mechanics, controls and interfaces. This situation indicates that identification, that is, “the transformation that takes place in the subject when it assumes an image” (Lacan, cited by Taylor, 2003), is a much more radical condition of “counting as one” than is perceived by the approaches that are built around the inside/outside duality. This fact is also stated by Lefebvre (1991) who observes that “representational spaces (…) need obey no rules of consistency or cohesiveness” (p. 41). He points out the arbitrariness of representations (and therefore the subject positions produced by them) by asking “what does it mean for example to ask whether perspective is true or false?” In the end, “all representations of space are abstract” and are “subordinate to their own logic” (p. 41). Florenski (2001, pp. 114-115) also points up this fact when he says that

representation is always signification (…) to ask whether a representation is natural or attempts a style makes no sense (…) one can only ask whether the applied style attempts to be naturalistic. Style is the inescapable nature of all repesentations.

This is another way of expressing that identification can take place under the weirdest configurations of visual style and spatial order, since they are all perceived as natural within their own style, and a spectator is therefore always ready to live up to the variety in which they may come.

Clemens (1996) draws attention to this active and performative nature of identification and states that it is by no means a simple registration of fact, but rather having the simultaneous status of cutting and suturing through which the human “identifies itself as a delimitable being-in-the-world, [and as] one object among others” (p. 73). This simultaneous status of cutting and suturing is closely related to the way the body, including the eye (or seeing) gets caught into the semantic web of the ludic discourse. As Zizek (1992, p. 21) explains, central in grasping this process is Lacan’s distinction between drive and demand. The central thought here is that in the symbolic order, the division of bodies into zones is not determined biologically, but through discourse. Hence, body parts or zones are marked not by their position within the human anatomy, but through the way they got themselves caught into the semantic web of the symbolic order. The body and its drives are rendered through the symbolic so as to be inscribed with varying sets of gestures, substances, values and replacement parts. Since the satisfaction of drives can only be attempted through this rendered body, Lacan uses the capital letter D, standing for Demand, which is how he calls such rendered drives.

It was probably Bernard Suits (1978) who included the notion of demand for the first time into a definition of play, saying that it is an activity “where the rules prohibit more efficient in favor of less efficient means” (p. 34), which is another way of expressing that players must satisfy drive through the way in which the game has reconfigured their body and the world within which they act. A term that may be useful to address such operations of demand on the eye (or seeing) is game view (Schreiber and Brathwaite, 2009, pp. 25-26). However, it is important not to mistake perceptual view for the broader field of gaze, since gaze is not simply perceptual view, but rather an order that constructs an artificial point-of-view and then naturalizes it as if it were perceptual view (the world presented as if it were “someone’s perception of it”). Hence, subjectivity is produced through a broader field of gaze that is “a structure of seeing” (Rehak, 2003, p. 119) and simulates an artificial view as if it were a perceptual view. In other words, “That’s me” (subject in space) and “That’s what I see” (spatial representation misrecognized as perceptual view) are both produced by the field of gaze, equally artificial but interdependent in the maintenance of their naturalizations.

It appears obligatory to consider ludic spaces from such a demand perspective then. Rapoport (1979) points out the importance of semantic webs in the differentiation of space into place so as to “indicate that [we] are here rather than there” (p. 3). In other words, the making of place is the marking of space, it is the “ordering of the environment by abstracting and creating schemata” (p. 3) and the “purpose of structuring space and time is to organize and structure communication” (p. 9). Hence, we do not speak of a “random assembly of things [but of the] expression of domains” (p. 9). According to Lefebvre (1991), this is “logico-epistemological space, the space of social practice” (pp. 11-12), which is underlied by “codifications produced along with the space corresponding to them” (p. 17). These codes must be regarded as “part of a practical relationship, (…) part of an interaction between ‘subjects’ and their space and surroundings” (pp. 17). This “appropriated space” (p. 31), which is the connotative sum of physical and mental space, is then where subject and place, both being products of the same codification, come into mutual existence.

Interfaces, too, can be seen from this perspective. Following Flanagan’s (2006) observation that “interfaces are abstractions that can be said to describe an underlying topology of the self” (p. 312), it appears that they embody the semantic web that we are caught in at exactly the moment we start to interact with them. However, we need to take into account that it is not merely the interface itself that re-skins the player, since the interface must be regarded as a re-skinned body/space, too. The relation between player and interface/screen space must be seen as an encounter of two skins/bodies caught simultaneously into varying but mutually accessible architectures of the same semantic web. But where is this semantic web then to be found? As Flanagan (2006, p. 315) explains,

the equivalent to skin and its markings lies in code, in programming. Computer programming provides the ultimate map, for it is both a language with its symbolic representations, and itself a body, a place where language transcends representation and becomes action.

The program reskins both of these participants with different but by both participants mutually and meaningfully recognized zones. With meaningfully recognized zones, I mean to say that the demand of a subject always involves a certain vision of the demand of the other, because ultimately, the reskinning of bodies is also an act of inscribing gaze (the demand of the other) onto each other’s skins. Running against each other in order to satisfy their demands, intercourse between the two subjects interface and player will only take place if the conditions put forward by the semantic web are met, that is, the confronted subjects must negotiate the satisfaction of their demands in a way recognized by the semantic web that produced them. What is recognized as a valid exchange changes, of course, from game to game. This broader framework of valid exchange, which re-skins both player and interface simultaneously, also explains in particular why, as long as the contrivance or appropriation is successful, a player can identify with any type of visual representation of presence within ludic space, be it through subjective camera, side-view, top-view, in-game avatars, or all of them at once, since the player’s subjectivity and the interface are constructed as each other’s mirror reflections: they see each other in each other.

The fundamental importance of semantic webs in the re-zoning of bodies and spaces indicates that one must see a condition of the semiotic type here, one that doesn’t simply turn inside or outside based on camera distance or angle, but one which allows it to assume any kind of position as a property of the self, and this is exactly what suture achieves: to be as is. One assumes the image, despite its radical otherness; the properties of the image one assumes come second. It may come across as striking to realize how old this particular notion of “counting as one” is: the verb assume is etymologically rooted in the latin sum (to be, to amount to), and esse (being), from which also the word essence derives. The connection to the word essence is interesting because it lays bare a complex, almost tautological aspect of this kind of presence: A being whose ontological basis is founded onto itself, as is exemplified in the way God answers Moses’ call for providing an identity: Ego sum, cui sum; “I am who I am.” This is the biblical Yahveh, the name of God, a being whose characteristic property consists of being. In short: God is. On another account, this is also the essence of the narcissistic condition, in which one assumes one’s own shadow reflection (imaginis umbra) in order to erect an image of one’s self so as to gain a substance and a proper name: “That’s me” (Stoichita, 1997, pp. 32-33). In other words, one maintains a self-image on the basis of an image that has been mistaken for the self. In the case of ludic identification, we could say that the sum we talk about is a connotative sum (a self-image): that between a signifier (the human borrowed by the game from the real world) and a signified (the logical and semantic form of the game). This allows us to draw the conclusion that being a player is to count oneself as the position produced by, and taken in, in symbolic space, and that through this, one has become a sign.

How does a human find itself reduced (or, if you prefer, elevated) to a sign, to a game-generated subject within ludic space? An explanation to this is given in one of Roland Barthes’ (1991) early studies that is concerned with myth as speech. Myth as speech, according to Barthes, borrows the signs from a first order language (which could be any token of reality—a human for example—that has been already rendered into a sign by other discourses), and strips them from their already existing signifieds, thereby turning them into empty forms (signifiers), and associates them then with the set of signifieds of its own symbolic order (p. 113). This operation of discourse on discourse, which Gregory Bateson (1983, pp. 315-316) defines as meta-communication, renders the invaded objects into metaphor, and causes them to shift on a vertical axis, into a different logical state (a different set of rules that govern a productive articulation of its own kind), one which radically alters the meaning and capacity of every contrived object or action. This can be said to apply to games too, since games recruit already existing signs as to give them functions as signifiers in their own systems. Games can be then partly defined as second-order languages that recruit the signs of first-order languages as their signifiers. As soon as the signs of the first order language are dislocated by the operations of the second order language, they retreat into the state of being signifiers in the latter (1991, p. 113). The important aspect here is that through its borrowing, the signifier-turned-sign gains a double sense: it is simultaneously a sign in a first order language, and a signifier (associated with the signifieds) in the game’s second-order language. Through the borrowing and association with the signifieds, the borrowed sign becomes rooted into the realm of the game so as to express meaning in terms of the logical form by which it has been invaded. For example, the game of football utilizes real humans, real-world physics (such as gravity), and real objects (a ball, a framework made of wood), all of which could be considered as already having meaning in the real world (thus, being sign systems, or first order languages), and uses them as the empty forms (signifiers) of its secondary order language by filling them with its own logical form (signifieds). The logical form redefines and reconfigures the emptied signs so as to make them functional in the fictional universe of the game, thereby also enabling the ludic signification process. Humans, physics and objects that have been borrowed are still real to some extent; however, humans only gain functionality by pretending not to have any hands, and gravity has gained new functionalities by being put into the service of the fictional universe of the game. In other words, what has been borrowed from reality is not exactly the same as with what has been given back (Barthes, 1991, p. 124). As Malaby (2007, p. 96) has stated, we must speak of “contrived contingency” here: the utilized elements acquire new meaning through their subordination to the definitions and delineations of the ludic discourse. Real properties and real actions of real humans and processes no longer denote what they used to denote, because “when it becomes form, the meaning leaves the contingency behind” (Barthes, 1991, p. 116).

It can therefore be said that through the rendering of first-order languages into metaphor, games invent one world scheme in terms of another. The invented world scheme must be regarded as the knowledge about a certain truth that was outside our perception until its inception through the ludic call. Despite the materiality of the utilized beings and objects, we do not deal with empirical facts here anymore, but with symbolic values put into circulation by ludic discourse. To consider these values as half real-half fiction, half inside-half outside, means that one assigns substance to what has become form, thereby seeing empirical facts in what is signification, and a causal chain of real events in what is a system of values (Barthes, 1991, p. 130). Indeed, to the player, a game seems to be stripped from the motivations that created it and is consumed with a sense of logic, as if the signified were set up by the signifier, and as if the image led us naturally to the concept, which results in one seeing an inductive system in what is actually a sign system (Barthes, 1991, p. 130). This complex process of the naturalization of the artificial is achieved by a human’s submission to several interrelated orders of misrecognition. The next section deals with these misrecognitions.

The Compass of Disorientation

In a paper on the concept of misrecognition in psychoanalysis, Clemens (1996) provides us with what he has named a “compass of disorientation”. Here he lists eight orders of misrecognition (see Table 1) through which Lacanian theory explains the production of subjects. Each of the misrecognitions are also matched with equivalent figures of speech in rhetoric, something which immediately brings into one’s mind the notion of procedural rhetoric in Ian Bogost’s (2007) work on persuasive games. Clemens (1996) draws attention to the fact that “for Lacan, it is precisely rhetoric that attempts to ground being” (p. 81).

| Mis-Rec. |

Rhetorical Figure |

Figure Description |

Psychoanalytical Description |

Corresponding Player Phrase |

| 1st |

Metaphor |

Treating an object as if it were another object |

Seeing one’s image “over there” as if it were “over here” |

“That’s me” |

| 2nd |

Synechdoche |

Substitution of a part for a whole |

Mistaking one’s own fragmentation for an unified self |

“It functions” |

| 3rd |

Prosopopoeia |

Anthropomorphism |

Misrecognition of the image as human, despite the fact that it is an artefact |

“It’s alive” |

| 4th |

Prolepsis |

Anticipation ofthe future |

The mistaking of a promise for an already accomplished fact or possible manifestation |

“I am…” |

| 5th |

Metalepsis |

Trope of a trope |

Miscrecognition of the status of this promise, which is actually a promise of a promise |

“…was, and will be” |

| 6th |

Antithesis |

Counter-proposition that denotes a direct contrast to the original proposition |

A misrecognition that proceeds by inverting the image’s significance and value |

“I’m the reason” |

| 7th |

Catachresis |

Misnaming |

The misrecognition of the stage as stage. |

“This pretends to be a game, but it can’t fool me: this is a game” |

| 8th |

Irony |

Incongruity between the implied and literal meaning |

The misrecognition of the entire scene as if it takes place, despite its impossibility. Everything transpires precisely because of its non-existence. |

“Impossible, therefore.” |

Table 1. The compass of disorientation: eight orders of misrecognition briefly described and tagged with corresponding figures of speech.

Clemens (1996) describes the first misrecognition, metaphor, as primarily spatial (p. 74). It is a stationary transport in which “one is caught up in the lure of spatial identification” and one sees “one’s image over there as if it were over here” (p. 74). Bateson (1983, pp. 316-318) explains this as the effect of meta-communication, since a game frames the relationship between objects anew and causes an inversal similar to figure-ground inversals in optical illusions. Objects shift into a new logical state and no longer denote what they used to denote. Besides, what they now denote is something fictional. Barthes (1991), as already mentioned, explains this inversal as a second-order language dislocationg the signs of a first-order language so as to make them work under its own signification chain. Indeed, all myth is metaphor.

The second misrecognition is the “mistaking of one’s own fragmentation for a unified self” (Clemens, 1996, p. 74). It is based on an “overlooking of the external, material support of one’s image” (the stage, the surface), something which allows us to say that the produced identity of the subject is sort of a “non-existing prosthesis that helps one to stand up straight within oneself” (Clemens, 1996, p. 74). Interestingly, this notion of a support that enables one to stand erect, can be traced back to the term colossus, which expresses the erection of something living and persistent inside the twin-image (Stoichita, 1997, p. 20), that is, to turn the flat (not only in the sense of being two-dimensional, but also as in “lying flat on the nose”) image into a clay figure or erect statua (statue) by filling it with substance and thereby giving it three-dimensionality (pp. 16-17).

The third misrecognition “illicitly renders the inhuman human, by giving a face to a thing” (Clemens, 1996, pp. 74-75). This is primarily to repeat in an image what has been lost, or simpler, to animate the dead, something which according to Stoichita (1997, p. 20) marks the birth of the tradition of western mimesis and is the main motif behind the long story of image as placeholder.

The fourth and fifth misrecognitions are related to time rather than space, because they are about a promise, or more precisely, about the promise of a promise that is misrecognized as an “already accomplished fact or possible manifestation” (Clemens, 1996, p. 75). According to Stoichita (1997, p. 21), this is a defining property of images (or representations), because their primary impact is to point at their own time, the time in which they exist, and thereby cause the setup of a time outside of the flow of time. Here, the image is not just a projection in the visual sense, but also in the mental/cognitive and temporal sense: it comes from the future, and makes one think “to already be” (This is me, here, now), which is “a prefiguration of power linked with the symbolic [and] governed by a strange temporal structure, that of the already/not-yet” (Clemens, 1996, p. 75). This is maintained by a doubled illusion: not only are the screen images we see and which make us assume an image of the self, illusions, but also this very image of the self-caused by these images is an illusion. Hence, what is misrecognized as presence is the projection of a ghost of a ghost, of a future of a future, “something that might never receive actualization” (p. 75): This is me, here, now, is then an illusion of the finest sort. And it leads to the sixth misrecognition: “one mistakes what the promise holds out” and as a result, “apparition is greeted with jubilation” (p. 75). But what is greeted with jubilation is not only to be a ghost, but to be a ghost in the machine, since what seems like being in power is only to function as a gear in the machine, that is, the interpellated subject carries the system on its back, while it thinks to sit on top of it. In other words, the subject “inverts the image’s significance and value” (pp. 75-76.) and perceives as a privileged position what is just one of the countless functions that need to be performed for the system to reproduce itself, including its carriage-subjects.

The two final misrecognitions, catachresis and irony, require a bit of a special treatment, because they relate to how the whole stage is misrecognized. The misrecognition of the stage as stage is a very interesting one, because one is aware of its status of fiction but nevertheless proceeds as if it were not. The staging occurs, but ultimately cannot be grasped. This, in the final analysis, leads to irony, because everything takes places despite its impossibility (Clemens, 1996, pp. 76 and 80). Clemens goes on to say that “this is not a fantasy in the sense of wishful thinking or of an absurd or offensive content, but rather an empty and fractured frame that is organized according to eminent logical exigencies, and devolves from logic running against its own limits” (p. 80). Such “disappearance of the initial cause from the mechanical field that it founds” (Copjec, cited by Clemens, 1996, p. 80), has been addressed with terms such as naturalization and non-knowledge. Barthes describes both as essential aspects of mythmaking, aspects that can also be said to apply to games: when the game’s invitation to join its unique signification process finds us in our individuality, the game, which is after all a historical artefact, appears to us as if it were natural, that is, as if it were the most logical thing for it to spring out of contingency the way it sprung (Barthes, 1991, pp. 123-124). The ludic call presents the game’s existents and events as though they were magical items that feel as if they have been created solely for us, in exactly the moment of our encounter with them (p. 123). This is the result of the successful contrivance between the object that has been borrowed from the first order language and the logic of the second order language. Barthes (1991) describes this contrivance as a turnstile that puts into motion the dual sense of the signifier-turned-sign: we can no longer distinguish between the sign as meaning (its state in the first order language), and the sign as empty form (its state as the signifier in the second order language) (pp. 113-119 and 121), and it is exactly this state of not being able to distinguish between these two states that generates the irresistible magic that makes the call of the game so powerful. This mechanism is central to the production of the ludic subject: “player” neither stands for the real human (outside), nor for the abstraction that the concept puts forward as a role (inside); it is the inability to distinguish between the two, between the inside and outside, something which causes one to take on a position that is non-existent (symbolic).

This condition of standing on a ground that exists solely because of its non-existence must be overcome by the subject with a sort of a non-knowledge. In order to maintain the illusion of agency, it is thus central that the subject remains unaware of the fact that the source of its capacity is not in itself, but that it is produced by the position which it holds within the symbolic order (Zizek, 1992, p. 29). Instead it must experience the fact of being a product of ludic discourse in a way that allows it to find its produced self as truth. This becomes possible through what Lacan calls the answer of the real, a defining moment in our encounter with discourse, which sets up the illusion that we have been always already there as we are. According to Zizek (1992), the answer of the real can be regarded as the repetition of the phallic gesture of the symbolic order in response to a loss of reality (p. 29). In the case of games, this is a response to the sudden thrownness into the alien game world. In order to transform the resulting utter impotence of this thrownness into its opposite, agency, the player must find a way that allows it to take on responsibility in the sudden appearance of this ludic reality: it needs a token of truth that suppresses the arbitrary nature of its presence and confirms its faith into being a unique and omnipotent subject (p. 30). In other words, it needs an event, “the experience of being influenced, of a connexion” (Wittgenstein, 1953, p. 71e) that allows it to re-inscribe itself into what it believes to be a causal chain of events that respond to its demands and manipulations—“’the experience of the because” (p. 72e). A typical example for this is the “A-ha, see? I did it!” moment, when one uses the controls of a game for the first time and manages to make something happen. When the player’s action accidentally produces an event, the playing human, perceives this accident as the success of its own communication: it put a demand into circulation and its demand has been answered (Zizek, 1992, p 31). Zizek states:

For things to have meaning, this meaning must be confirmed by some contingent piece of the real that can be read as a “sign.” The very word sign, in opposition to the arbitrary mark, pertains to the “answer of the real”: the “sign” is given by the thing itself, it indicates that at least at a certain point, the abyss separating the real from the symbolic network has been crossed, i.e. that the real itself has complied with the signifier’s appeal. (p.32)

He further states that it is only through non-knowledge that this successful misunderstanding establishes the psychic reality that allows for a meaningful encounter with a number of naturalized entities (pp. 33-34). Hence, game-produced subjectivity must be experienced as an immediate quality of one’s individual presence—the “purest crystal,” as Wittgenstein calls it (1953, p. 44e)—and not as being maintained by the performative act that produces it as such. In other words, for the player, the as if is, and can only be, real.

Conclusion

As I have pointed out in this paper, the field of game studies has yet to develop a unified player theory which has the capacity to explain the complex relations between player, game space and visual representation. I have drawn particular attention to the points of that made repeated failure in this regard due to a prevailing inside/outside duality that seems to create confusion in locating the player’s position within the mixed field of physical and virtual space. This confusion has in particular to do with a failure to recognize a player’s status as spectator, who, as opposed to the idea that he navigates through space, rests at a fixed point in physical space so as to obey a scenographic arrangement that makes the staging of such navigation possible.

This article also attempts to overcome the aforementioned duality by interrogating the notion of linear perspective. To do so, I use the notion of inverse perspective, a concept that does not only refer to a certain mode of representation, but also to a certain philosophy in art criticism. This philosophy emphasizes a highly unified and immersive relationship between spectator and artwork. Based on the framework that this philosophy puts forward, and especially around the notion of (divine) light, I have established a connection to the concept of gaze and to the theoretical framework of psychoanalysis.

Based on the earlier works of game studies scholars who attempted to use Lacanian psychoanalyses, in particular Bob Rehak and Laurie Taylor, I have used interpretations of Lacan’s theory and some of his central concepts, such as Demand, in order to shed light on the complex relationship between player, space and gaze. The point that I emphasize here is that player and space are simultaneously produced and mutually dependent constructions within the broader field of gaze. This is a condition that is difficult to capture with approaches built around an inside/outside duality, since we need to take into account the symbolic order as the fundamental ground on which subjectivity and space are constructed. Such an approach suggests that reference to real physical space must be suspended to some extent in order to deal with the problem of subjectivity in a thorough way.

In order to deal with the production of subjectivity itself in a detailed way, I have used Justin Clemens’ “compass of disorientation” and discussed several of the orders of misrecognition which he puts forward. In my discussion, I have made particular use of the works of Roland Barthes, Victor Stoichita, and Slavoj Zizek. I hope that I have thereby been able to make a contribution to the understanding of how a game produces subjects that assign the status of the real to the “as if.” I believe that in the future we need to see more studies that attempt to overcome the prevailing inside/outside duality, especially studies that emphasize the simultaneity of the production of ludic space and ludic subjects.

– All images belong to their rightful owner. Academic intentions only.-

References

Aarseth, E. (2001). Allegories of Space: Spatiality in Computer Games. Zeitschrift für Semiotik, 23(3-4), pp. 301-318.

Aarseth E., Smedstad S., & Sunnana L. (2003). A Multi-Dimensional Typology of Games. In M. Copier, & J. Raessens (Eds.), Level Up: Digital Games Research Conference (pp. 48-53). University of Utrecht Press.

Barthes, R. (1991). Mythologies. New York, NY: Noonday Press.

Bateson, G. (1983). A Theory of Play and Fantasy. In J. Harris, & R. Park (Eds.), Play, Games and Sports in Cultural Context (pp. 313-326). Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics Publishers.

Bogost, I. (2007). Persuasive Games: The Expressive Power of Video Games. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Clemens, J. (1996). The Lalangue of Phalloi: Lacan Versus Lacan. Umbr(a), 1(1), pp. 71-85.

Flanagan, M. (2006). Reskinning the Everyday. In M. Flanagan, & A. Booth (Eds.), Re: Skin (pp. 303-319). Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Florenski, P. (2001). Tersten Perspektif [Inverse Perspective]. Istanbul, Turkey: Metis.

Graça, M. (2006). Cinematic Motion by Hand. Animation Studies, 1, pp. 1-7.

Harris, C., & Park, R. (1983). Play, Games and Sports in Cultural Context. Champaign, IL: Human Kinetics.

Hernandez, M. (2007). The Double Sense of Animated Images. Animation Studies, 2, pp. 36-42.

Hitchens, M. (2011). A Survey of First Person Shooters and Their Avatars. Game Studies, 11(3). Retrieved from http://gamestudies.org

Kolker, R. P. (1998). The Film Text and Film Form. In J. Hill & P. Church-Gibson (Eds.), The Oxford Guide to Film Studies (pp. 11-23). Oxford University Press.

La Grange, A. (2005). Basic Critical Theory for Photographers. Oxford, UK: Focal Press.

Lefebvre, H. (1991). The Production of Space. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Malaby, T. (2007). Beyond Play: A New Approach to Games. Games and Culture, 2(2), pp. 95-113.

Pallasmaa, J. (2005). The Eyes of the Skin: Architecture and the Senses. New York, NY: John Wiley and Sons.

Rapoport, A. (1979). Cultural Origins of Architecture. In J. Snyder, & A. Catanese (Eds.), Introduction to Architecture (pp. 2-20). New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

Rehak, B. (2003). Playing at Being: Psychoanalyses and the Avatar. In M. J. P. Wolf, & B. Perron (Eds.), The Video Game Theory Reader (pp. 103-127). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ryan, M.-L. (2001a). Narrative as Virtual Reality: Immersion and Interactivity in Literature and Electronic Media. Baltimore, MD: John Hopkins University Press.

Ryan, M.-L. (2001b). Beyond Myth and Metaphor – The Case of Narrative in Digital Media. Game Studies, 1(1). Retrieved from http://www.gamestudies.org

Sayın, Z. (2001). Sunuş [Presentation]. In P. Florenski (author), Tersten Perspektif [Inverse Perspective] (pp.7-31). Istanbul, Turkey: Metis.

Schreiber, I., & Brathwaite B. (2009). Challenges for Game Designers: Non-digital Exercises for Game Designers. Boston, MA: Charles River Media.

Stoichita, V. (1997). A Short History of the Shadow. London, UK: Reaktion Books.

Suits, B. (1978). Grasshopper: Games, Life and Utopia. Edinburgh, UK: Scottish Academic Press.

Taylor, L. (2002). Video Games: Perspective, Point-of-View and Immersion (Unpublished master’s thesis). University of Florida, Gainsville, FL.

Taylor, L. (2003). When Seams Fall Apart: Video Game Space and the Player. Game Studies, 3(2). Retrieved from http://www.gamestudies.org

Wells, P. (2006). The Fundamentals of Animation. Lausanne, SUI: AVA Publishing.

Wittgenstein, L. (1953). Philosophical Investigations. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Zettl, H. (1990) Sight Sound Motion: Applied Media Aesthetics. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth Publishing Company.

Zizek, S. (1992). Looking Awry: An Introduction to Lacan Through Popular Culture. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.