PDF Download

PDF Download

Abstract

Within the broad framework of audiovisual theories, this paper deals with the analysis of narrative time in video games. Starting with the concept of participation time, which is taken from the interactive media, the now classic concepts of the narratology of film studies are applied to clarify the main mutual influences between the two media in relation to narrative time.

Unlike the cinema, the narrative character of video games is not always clear. Generally, video games are always games and often also stories. Certainly, the playable character of these stories confers on them a few specific characteristics that need to be explored.

Two aspects of narrative time are relevant here. Firstly, the loop as an elementary control structure of computer programming and as a characteristic narrative form of time structure in video games, and secondly, the paradox of travel in time in the discrepancy between the time order at the level of the story and at the level of the narrative.

Keywords

Video games, film, audiovisual language, narrative time, participation time

Introduction

In cinema the action is narrated in the present tense. The screening of the film actualises the story each time, even though it was filmed in the past. For Jost and Gaudreault (1995, p. 111) film time relates states or events from the past which we recall as they unfold. The film image shows how things develop, it shows us the past as it takes place before us, in the present, and takes its time to show it.

According to Neitzel, however, the narrative time of video games must be viewed differently. Here, gameplay is the fundamental and distinguishing characteristic: “The process of playing a computer game thus corresponds to the process of narration. This process leaves behind traces on the level of the discourse, which makes up certain relationships with the level of the story, for example, in respect to temporality” (Neitzel, 2005, p. 236)

The player’s actions in the game constitute perhaps the most important difference between video games and other media such as cinema or literature, where the viewer or reader does not intervene. Video games are always games, although they are also often narratives. In the case of narrative games, which are our main focus, the narrated story is determined by the playable nature of the medium. The narrative time in video games will, therefore, largely depend on the player’s actions.

In this paper, we will follow the theoretical perspective of narratology for the analysis of narrative time, starting from the adaptation of G. Genette’s literary theories to film studies. Naturally, the narratological analysis of video games presents peculiarities that we must fully take into account and that give the key to the fundamental differences between film and video games, although also to their extensive mutual influences. We recall that narratology is presented as the study of narrative and thus is applicable to different media, provided they are narrative.

Given that the discourse is created as such from the experience of its enjoyment, a fundamental distinction to be made with regard to the narrative temporality in video games is the control of time by the player.

In interactive media, according to Maietti (2008, pp. 63-64), there are two types of temporal duration, object-controlled duration and experience-controlled duration. In the first, temporal duration depends on the medium and is independent of its reception, as is the case in film, whereas in the second, the player controls the duration of the game in their action of playing. Generally, MMOG (Massively Multiplayer Online Game) impose a tighter control over time, since this must necessarily be shared by all the users, whereas in single player games, the player can have greater freedom to control the time. We’ll see how this is particularly true for loops, which are used in single-player video games, such as Tomb Raider or Resident Evil but are unviable in an MMOG such as Counter Strike, which imposes a rigid, standardised duration on all participants. Of course, single-player games can have a system-controlled duration, for instance in most racing games, such as Need for Speed, or sports games, including football and others, such as FIFA. Temporality is never a simple factor in any case, given that the narrative is produced from the interactivity of the discourse.

Participation time: dual temporality in video games

According to Genette (1991 and 1998), dual temporality is required to define a narrative, i.e. there are two temporal components, given that a temporal sequence of events does not in itself define a narrative. Therefore, as regards the dominant temporal relation, in narratives such as books or films, there is a relationship between story time and discourse time, which is required to define any narrative. Eskelinen (2004, p. 39) argues that, based on the traditional definitions of narratology, narrative time in video games should be defined as the relationship between user time and event time.

In this same area of concern, Juul (2005, p. 141) proposes a relationship between what he calls play time and fictional time. Make-believe games have a dual structure, in the sense that the player’s actions belong to a different world from the character’s actions, but the two are connected. Time is the variable that gives us the key to this relationship because it is time in the real world, play time, and in the fictional world, fictional time, time in which the action unfolds.

Although Eskelinen and Juul use different terms, they refer to the same two concepts as Genette – user time and play time are the equivalent of discourse time and event time and fictional time are the equivalent of story time.

However, in Maietti’s view (2008, p. 70) we must avoid the problems involved in determining the duration of an event in the fictional world according to the duration it would have in the real world. In other words, determining play time as the actual time playing can lead to misunderstanding or at least does not contribute to the narrative understanding of the game. Finally Maietti suggests that research should be undertaken into the time of the interaction, the user’s access to the fictional world through the interface (Maietti, 2008, p. 72).

Undoubtedly, the application of narratology to the analysis of narrative time in video games raises some issues. In interactive media, the discourse is not completely fixed or predetermined, instead most of it is generated during the interaction or participation. Since time is linear, the story generated is linear. But the resulting text is not all the interactive text, nor does it enable us to fully understand its nature. At this point we must consider the player and the games, and in this sense, the player’s time and the game time in terms that are rather more abstract but useful from an analytical point of view.

In this sense, fictional time or time of events can be defined as the story’s internal intradiegetic time. Whereas, in our view, game time or user time should refer to the time the game gives the player. This time is written in the rules of the game, but is manifested in playing and should include the ability or possibility that the game gives the player to change the narrative time. This is the equivalent to Genette’s “pseudotime” (1991, p. 144) and measures not only the narrative speed but also, as is inevitable in an interactive medium, the modification of the narrative time by the player. This second aspect of user time, the modification of the narrative time, can only take place at the interface, as noted by Maietti (2008, p. 72). We can call it participation time, as it puts the focus on the user’s interaction in the game through the interface, in the modification of narrative time through the gameplay. In functional terms, this participation time will express the player’s progress in the game, i.e. their linear progress through the discourse via the games.

The narrative time is defined in the same way as in film and literature, as a dual temporality between the story time and discourse time, but in video games there is tension between this narrative time and the user’s participation in the game.

In video games, the dual temporality is defined by the story time and participation time. The story time is the same concept as we have seen throughout the narratological tradition, the internal time in the story which is told, but the participation time is new to the study of video games. It is equivalent to discourse time in film studies but it is not the same, since in film, the narrative time, the duration for example, is fixed in the story and does not depend on viewing. In video games, however, the participation time may be not fixed before playing, and may depend on the player’s actions in the game through the interface. For instance, the player’s skill can make the climbing of the telecommunications tower in Tomb Raider, either a fast and exciting linear adventure lasting 10 minutes or, following successive failures in the ascent, a slow and frustrating repetitive action that lasts twice or three times as long. The story time, and the story itself, are modified by the player’s actions.

Before analysing each aspect of narrative time, we must take into account that the participation time depends on the rules of the game. If the rules allow for it, the player can, by their play, modify the narrative time, i.e. the relationship between the participation time and the story time. In other situations, we find a set time, i.e. a time controlled by the system and by the rules. Eskelinen refers to this same distinction as “event time” for games in which the player can change the narrative time and “set time” for those in which the time is set in the rules.

The dual temporality of all narratives –in film, literature or video games– imposes the variables for the analysis of the narrative time, which are, in any event, determined by the relationship between the discourse or participation time and that of the story time. These variables, according to Genette, are order, duration and frequency. We will now focus on the most contentious issues and also those that are particularly distinctive in relation to each of these variables in the analysis of the narrative time of video games, especially in relation to the concept of participation time.

Temporal order: paradoxes of travel in time

Based on Genette (1991, p. 91), but adapted to the peculiarities of cinematic storytelling (Gaudreault & Jost, 1995, p. 112), we can distinguish three possibilities for the organisation of time: linear time –pure chronology, coincidence, respect for order– between the story time and the discourse time; and two types of anachronism, analepsis (-lepsis, take, ana-, after), the subsequent recall of an event prior to the time of the story, and prolepsis (-lepsis, take, pro-, before), where the event takes place before its normal order in the chronology. In the cinema the terms flashback and flashforward are often used, but they have the drawback of referring only to the visuals. Therefore, there will always be a “récit prémie” or first narrative and an anachronism, which is a second narrative, inserted into the first.

In film, it is often the words that indicate an anachronism, its scope and breadth. Flashbacks combine a verbal backtrack with the visual representation of the events. Especially in classic cinema, there are cues and conventions that denote a flashback (gaze into the distance, fade to black, different appearance of the narrating character, the switch from an indirect style –verbal discourse– to a direct one –dialogues–, etc.). There are numerous examples of analepsis in the cinema, from the most classic cinema to the most recent, such as The Bad and the Beautiful, Citizen Kane, Sunset Boulevard, Lola Montès, Mr. Arkadin, and many others.

Flashbacks or analepses have been used in the cinema almost since its inception, and certainly from the classical period to the present day, due to their dramatic effect, increasing the engagement of the viewer who wants to find out how a particular situation has come about. As a linear narrative medium, anachronisms introduce a non-linear order in the storytelling.

Prolepses, on the other hand, are much less common in the cinema than analepses, which are not only common but much conventionalised in their narrative formulas. A film which contains both in a characteristic postmodern narrative puzzle is Pulp Fiction.

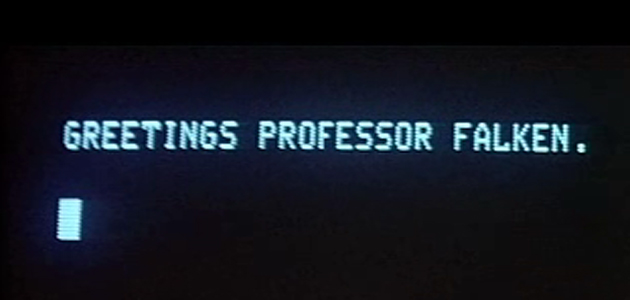

These two devices, analepses and prolepses, are difficult to apply to video games, due to what could be described as paradoxes of travel in time. Variations in the narrative order present some difficulties in video games, in relation to the fact that the game is a narrative experience that depends on the player’s actions to be narrated, which implies that analepses or prolepses will entail a problem of temporal paradoxes. Maietti (2008, pp. 60-61) states that, in interactive media in general, the order of the discourse sets the order of the story, limiting the narrative to a strict temporal dimension in the present tense. If, during an analepsis, the character who is the avatar of the player dies, this creates a contradiction in the present time in which they are still alive. The prolepsis may cause a distortion with regard to the character’s and the player’s knowledge. If the player obtains new information on the future state of the game world, when they return to their initial position in time, their knowledge will be different from that of their avatar. This difference in knowledge creates a paradox in the game, since the behaviour of the avatar will be based on information that the character cannot possibly possess.

Juul (2005), generally agrees with the above statements, in what he refers to as “chronology of time in game” (p. 147), chronological time. However he makes significant qualifications as to the possibility of there being anachronisms. In principle, games are narratives in the present, and there is a risk of creating temporal paradoxes if analepses or prolepses are introduced. However, there could be external analepses in mystery or detective games, etc., with cut-scenes or objects within the virtual world, i.e. in fictional time, which inform us about events in the past and help to solve the unknowns, such as, for instance, the Myst books. Zakowski, in his study of temporality in the Mass Effect series of games (Zakowski, 2014, p. 66), also connects the historical encyclopaedia the Codex to a link to the past, which he describes as a backstory, when information is provided on events prior to the present time in the main storyline.

The order in the narrative time must not be confused with time travel at the level of the story, where it is not the player who jumps in time, narratively speaking, but the character within the fictional world. Similar to time travel films, which can be completely linear in terms of the narrative, we can find an example of this in The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, where Link travels into the future, and returns to the present at the end of the game, and also the journeys made by Desmond Miles using the Amicus device in the Assassin’s Creed series. In the cinema, the Back to the Future film series is an example of this. In all these cases, they are still linear narratives.

Indeed, the majority of narrative video games found on the market have a chronological temporal order, established by the story. However, in our view this is not due to logical contradictions, which could be quite easily rectified by the use of rules, preventing, for example, a return from the analepsis if the character dies. Regarding the issue of the difference in knowledge, this also occurs in one of the most common video game formulas, the loop, but does not represent a significant narrative contradiction for the development of the game. On the contrary, it is a form of learning by the player, who guides their character using that new knowledge which the character, on the other hand, does not possess.

Eskelinen (2004) defines temporal order as follows: “In computer games this is the relation between user events and system events, or the actions of the player and their interaction with the event structure (happenings) of the game” (p. 40). From the moment we define the order in terms of the relation between user actions and system events, the question is whether or not the user affects the order in which the system events occur: they do in exploration games, but not, on the whole, in arcade games. The difficulty is that we are not referring to the order in a strictly temporal sense of past, present or future with regard to the story and the discourse, but to the moment, inevitably always in the present time, in which the user may or may not change the sequence of events. Indeed, we must study the order in narrative time in video games based on our definition of dual temporality, which we have seen in the previous section. The temporal order depends on the relationship between story time and participation time.

Some video games do not have a pre-established temporal order for the sequence of actions in the fictional world. This is what Herman (2002) aptly terms “fuzzy temporality” (p. 228), an indeterminate or inexact temporality, which heightens the player’s enjoyment in that the sequence of actions may vary, as their order is not relevant to the development of the story. The game unfolds in a given space but the different sequences or missions do not have a temporal order pre-determined in the rules. The journey through the space allows indefinite temporality in terms of the order without making the player feeling lost, since they know where they are, and time doesn’t matter. We find an example of this in the missions of Mass Effect. Although other video games impose a rigid succession in the sequence of actions, this order is, to put it one way, unspecific, in the sense that what really matters is still the spatial journey, which imposes a progression in space rather than a temporal order: a space-related time. This can be found in many games, such as those of Castlevania: Lords of Shadow or Tomb Raider and Silent Hill games series, etc.

Sometimes, in addition to a spatial anchorage, the passage of time can be established through objects. The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, which is a very comprehensive game in the way it deals with diegetic time, allows the player to be located at any given time due to the possession (or not) of certain objects, such as the Hero’s Bow, which is not lost in time travel. The possession of these objects indicates a linear progression in the game, one moment after another in which the Bow is not possessed.

Space and objects are common devices for marking progression in a game, while the temporal order, in narrative terms, is secondary in video games, unlike the cinema, where this order is narratively essential and always, apart from somewhat experimental exceptions, very clear. In video games, the objects that are possessed or missions that are carried out belong to a participation time, i.e. they mark the progress of the player in the game while the player develops the discourse.

While in the cinema, as we know, temporal order is a common device used, especially analepses or flashbacks, and it carries out narrative functions at various levels, from the characters’ psychology to the dramatic power of the story, in video games the narrative time is linear, in an almost always level chronological order. The most powerful device in video games is the participation time, which measures the user’s involvement, always within the rules, in the narrative time.

Duration and incoherent time

Firstly, in video games, the relative duration of participation time and story time is usually identical in that the actions of the game are displayed on a continuous plane. Therefore the most common way in the cinema to change the relative duration, montage, is not present in video games or is insignificant. In the cinema, the identity between the duration of the discourse and the duration of the story is known as a scene (Gaudreault & Jost, 1995, p. 127). The usual plane sequence of games in the first person, third person or in a God-like view indicates that that relationship of duration is strictly identical.

However, we must take into account what Juul (2005) calls “incoherent time” (p. 152), which refers to temporal violations of the game time-fiction time relationship. Juul identifies three types of violation, which are game pause, subjective time, and shorter game time than fictional time. In this last case, the violation comes from comparing fictional time with real time, such as in Heavy Rain, in the scene where Ethan Mars has returned from school with his son at the beginning of the game and the kitchen clock shows the story time, which is faster than real time. This treatment of time is only incoherent compared to real time. Juul himself refers to it as projection and it is the same as what is known in narratology as a summary, a summary of the story time in the discourse time, such as in the montage sequences of The Hudsucker Proxy or Up. In the case of the videogame Heavy Rain, the duration is controlled by the rules of the game, which impose on the player the difficulty of a reduced time to resolve the scene. In this case, participation time is controlled by the rules.

In the other two cases cited by Juul, pause time and subjective time, we can find explanations without turning to the concept of inconsistent time. In many games, the pause or stoppage of play itself by the player, leaves the story time in relative continuation, for example with the hearing of diegetic sounds. Although one might think that this is a narrative dilation, such as the famous slow motion scenes of The Wild Bunch, we cannot say that when a video game is paused this relates to any kind of narrative function. Rather, it is the participation time, which pauses the game and with it the discourse. The same applies to what Juul calls subjective time, a short pause that takes place when the player reaches a certain goal and changes level, such as in Super Mario 64. It may be considered as a dilation of participation time in relation to the story time, but it is not significant, in our view, in terms of the narrative.

Sometimes story time can be sped up or slowed down using coherent devices at an internal fictional level, such as in Majora’s Mask. Firstly, again we find a narrative summary, where the participation time is shorter than the story time. In addition, playing the Inverted Song of Time halves the passage of time, whereas playing the Song of Double Time takes the player straight to night time or the following morning. The two songs are diegetic and therefore slow down or speed up time from a diegetic point of view, which means that rather than a narrative problem this is an intradiegetic modification, as also happened in The Ocarina of Time. But this temporal modification, which does not alter the narrative time but the story time, forms part of the participation time, i.e. it is the player who, at all times, chooses to use or not the possibility of playing one song or the other and thereby change the time of the story. Here the progress in the game, which changes the story time, is produced by the use of certain objects.

Frequency: the narrative convention of the loop

According to Genette (1991, p. 172), frequency refers to the relation between the number of times an event appears in the discourse and the number of times it appears in the diegesis, i.e. the relations of repetition between the plot and the story. It is a mental construct, since a repeated event is never the same, nor is the repeated fragment of a discourse.

Genette establishes the following types of frequency, which are always considered as mental constructs, between the story (S) and the narrative discourse (N):

– Narrating once what happens once (1N/S): singulative narrative;

– Narrating n times what happens n times (nN/nS): an anaphoric type of singulative narrative;

– Narrating n times what happens once (nN/1S): repetitive narrative. Here the story is told from different points of view or using different styles;

– Narrating once what happens n times (1N/nS): iterative narration, which implies condensation.

In adaptation to film (Gaudreault & Jost, 1995, p. 131), the types of frequency are almost reduced to the singulative narrative, which is exemplified by almost all the films in the history of the cinema, narrating just once events that happen only once. There are, of course, exceptions, such as Rashomon.

Whereas the repeating narrative is an unusual form in the cinema, it has often been said that it is essential in video games, although certainly not in all video games. According to Eskelinen (2004, p. 41) we can distinguish two types of game according to whether the events and actions can happen only once or unlimited times. There is no middle ground: in many games, especially MMOGs, the actions are irreversible, and a previous situation cannot be repeated. In others, it is not only possible but necessary to keep on trying until the solution is found, and this is an option established in the rules of the game and used by the player. Thus, in video games where time is not irreversible, the loop is commonly used as a way of dealing with time.

The loop has become part of the very identity of video games. If the temporal order imposes linearity, and if the duration is identical in the dual temporality, the loop is therefore the most characteristic formula of narrative time in video games. So much so that when the cinema has sought to reflect or take narrative inspiration from video games, it has adapted the loop, which seems very odd. In fact, although until the nineties the use of the narrative loop was unusual and virtually non-existent in the cinema, since then it has been explored by some films, to some extent inspired by the interactive narrative of video games, such as Groundhog Day, Run Lola Run, The Rules of Attraction, Source Code, Triangle or most recently, Edge of Tomorrow.

According to Manovich, the loop is a repetitive narrative. The author, on identifying the three fundamental characteristics of video games, directly linked to the cinema, cites the differential movement, spatial montage and the narrative convention of the loop. In fact the loop, as described by Manovich (2005, p. 392) constitutes the basis of early cinema and computer programming and was used for technical reasons in the first cinema screenings in digital media, just as it was used, for the same reasons, in pre-cinema and early cinema. The loop is inseparable from video games, for instance until a certain objective is reached and the player goes up a level. In this sense we can consider that video games often incorporate a repetitive discourse, where the unity of the story is changed several times in terms of the discourse. Adventure games are perhaps the best examples. Silent Hill, Resident Evil, Tomb Raider, but also God of War series, Death Island, Batman: Arkham City, and many others, force the player to repeat particular moments or scenes of the game to continue to move forward. The loop is integral to progress in the intradiegetic action and it is the player who, subject to the rules of the game, repeats the action however many times they need in order to learn.

For Neitzel, the relationships between story and plot are marked by the fact that a game is basically repetition. Therefore according to Neitzel, the example of Murray on the multiform story of the film Groundhog Day is wrong, given that it is a multiform plot, “because the story has only one form. This form, however, is shown in text in several forms on the level of the plot. The story with its intrinsic meaning holds together the repetitions of almost always the same, which are played out on the level of the plot” (Neitzel, 2005, p. 236).

However, from our perspective, to say that a story is repetitive, i.e. in a loop, the repetition must be at the level of the discourse, on the level of the plot, and not at the level of the story, which remains one. This is Genette’s original definition of narratology which is supported by Manovich. According to analysis based on the narrative levels, the character, within the story, does not know that they are repeating the same moment because it is the player who, from outside the story, is repeating an event time and time again. The story time is singular and the participation time is multiple, therefore the loop is produced by the extradiegetic action of the player. This is the difference between a medium that is interactive, video games, and one that is not, film. In video games, participation time can explain the loop. In film, when this narrative form typical of video games is adapted, the player becomes the character, so that they, within the story, learn over successive repetitions how to act.

Whereas in Groundhog Day and the other films mentioned above, narrations clearly inspired by the characteristic loop of video games are not strictly loops, since there is a multiple discourse and story. This is a case of a singulative anaphoric narrative and not a repetitive narrative. The fundamental difference is the narrative level at which the repetition takes place: if the repetition is intradiegetic, this is an anaphoric narrative, and if it is extradiegetic, it is a repetitive one.

The case of Rashomon is different. We can observe that they are different discourses, and versions, of one and the same story. Here it is the character-narrators who tell, each from their own viewpoint, the same story. Following our explanation, Rashomon sets out two narrative levels. The first is the present tense, the narrators, and the second is the flashback, the story told by each of them. It is a structure at two narrative levels, which is similar, but not identical, to that of video games. Indeed, in video games, the player, in leading the narrative, bears some resemblance to a narrator who tells a story, and whom we see in the audiovisual discourse. Therefore, Rashomon is a narrative loop.

In video games, the narrative time depends on the relationship between the participation time and the story time: the same story is played several times, as many as necessary for the learning and enjoyment experienced by the player. The loop, then, depends on the participation time, which is external to the story time, and forms with it the dual temporality needed for any discourse.

Conclusion

The loop is a narrative device that places tension on the narrative time, i.e. the relationship between the discourse time and the story time. In the cinema, this tension has rarely been explored, and mainly in films inspired by the playable narrative of video games, as a narrative game. In contrast, in the cinema, analepses or flashbacks have a very long tradition, especially from the classical period, and this continues today. This temporal disorder is very useful in narration, allowing very effective devices to be used for linear media, adding to the emotional engagement of the viewer. As we have seen, this is virtually non-existent in video games.

The duration of video games is normally the scene, because cinematic continuity equates the duration of the story with that of the discourse. However, as we have seen, there are discontinuities, which have been especially useful to consider the concept of participation time, which marks the modification of the narrative time by the player, through their participation in the game.

The loop expresses everything said so far. It puts in tension the participation time –discourse time– with the story time. It is the player who, always within the limits of the rules, alters the temporal variable due to their need to learn, improve, understand the dangers etc. and who decides, perhaps because they have no other option, to enter a narrative loop, whose main function is to move the game forward. Here the tension between participation time and story time is clear. This formula, which in some form produces a crisis within the narrative itself, has become a key feature of video games. It has also been transferred to the cinema in films that have played with the narrative, although from a narratological point of view it is not the same type, since the cinema as a medium is not, nor will it be, an interactive discourse, which is a necessary condition of the narrative loop in video games, i.e. a condition of the participation time.

– All images belong to their rightful owner. Academic intentions only. –

References

Eskelinen, M. (2004). Towards computer game studies. In Noah Wardrip-Fruin & Pat Harrigan (Eds.), First person. New media as story, performance and game (pp. 36-44). Cambridge: The MIT press.

Gaudreault, A. & Jost, F. (1995). El relato cinematográfico. Cine y narratología. Barcelona: Paidós.

Genette, G. (1991). Discurso del relato Figuras III (pp. 75-327). Barcelona: Lumen.

Genette, G. (1998). Nuevo discurso del relato. Madrid: Cátedra.

Herman, D. (2002). Story logic: Problems and possibilities of narrative. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

Juul, J. (2005). Half-real. Video games between real rules and fictional worlds. Cambridge: The MIT press.

Maietti, M. (2008). Anada i tornada al futur. El temps, la durada i el ritme en la textualitat interactiva. In Carlos A. Scolari (Ed.), L’homo videoludens. Videojocs, textualitat i narrativa interactiva (pp. 53-76). Vic: Eumo.

Manovich, L. (2005). El lenguaje de los nuevos medios de comunicación. La imagen en la era digital. Barcelona: Paidós.

Neitzel, B. (2005). Narrativity in computer games. In Joost Raessens & Jeffrey Goldstein (Eds.), Handbook of computer game studies (pp. 227-245). Cambridge: The MIT press.

Zakowski, S. (2014). Time and Temporality in the Mass Effect Series: A Narratological Approach. Games and Culture, 9(1), pp. 58-79.

Ludography

Assassin’s Creed, Ubisoft; Gameloft; Griptonite Games, Canada, 2007-2014.

Batman: Arkham City, Rocksteady Studios, UK, 2011.

Castlevania: Lords of Shadow, MercurySteam; Kojima Productions, Spain; Japan, 2010.

Counter-Strike, VALVe Corporation, USA, 1999.

Dead Island, Techland, Poland, 2011.

FIFA, Electronic Arts Canada, Canada, 1994-2014.

God of War, SCE Santa Monica Studio, USA, 2005-2013.

Heavy Rain, Quantic Dream, France, 2010.

Mass Effect, BioWare, Canada, 2007.

Myst, Cyan Inc., USA, 1993.

Need for Speed, Electronic Arts Canada; Black Box Games; Slightly Mad Studios; Criterion Games, Canada; UK, 1994-2013.

Resident Evil, Capcom, Japan, 1996-2012.

Silent Hill, Konami Computer Entertainment; Creature Labs; Climax Studios; Double Helix Games; Vatra Games; WayForward, Japan, 1999-2012.

Super Mario 64, Nintendo EAD, Japan, 1996.

The Legend of Zelda: Majora’s Mask, Nintendo EAD, Japan, 2000.

The Legend of Zelda: Ocarina of Time, Nintendo EAD, Japan, 1998.

Tomb Raider, Core Design, UK, 1996-2013.

Filmography

Avary, R. (Director) (2002). The Rules of Attraction [Motion Picture]. USA; Germany: Kingsgate Films; Roger Avary Filmproduktion GmbH.

Coen, J. and Coen, E. (Director) (1994) The Hudsucker Proxy [Motion Picture]. UK; Germany; USA: PolyGram Filmed Entertainment; Silver Pictures; Warner Bros.; Working Title Films.

Docter, P. and Peterson, B. (Director) (2009) Up [Motion Picture]. USA: Walt Disney Pictures; Pixar Animation Studios.

Jones, D. (Director) (2011). Source Code [Motion Picture]. USA; Canada: Vendome Pictures; Mark Gordon Company.

Kurosawa, A. (Director) (1950). Rashômon [Motion Picture]. Japan: Daiei motion picture company.

Liman, D. (Director) (2014). Edge of Tomorrow [Motion Picture]. USA; Australia: Warner Bros.; Village Roadshow Pictures; 3 Arts Entertainment; Translux; Viz Media.

Minnelli, V. (Director) (1952). The Bad and the Beautiful [Motion Picture]. USA: Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer.

Ophüls, M. (Director) (1955). Lola Montès [Motion Picture]. France; West Germany: Gamma film; Florida films; Union-film GmbH.

Peckinpah, S. (Director) (1969) The Wild Bunch [Motion Picture]. USA: Warner Brothers/Seven Arts.

Ramis, H. (Director) (1993). Groundhog Day [Motion Picture]. USA: Columbia Pictures Corporation.

Smith, C. (Director) (2009). Triangle [Motion Picture]. UK; Australia: Icon entertainment international; Framestore; UK film council; Pacific film and television commission; Dan films; Pictures in paradise; Triangle films.

Tarantino, Q. (Director) (1994). Pulp fiction [Motion Picture]. USA: A band apart; Jersey films; Miramax films.

Tykwer, T. (Director) (1998). Lola rennt [Motion Picture]. Germany: X-Filme Creative Pool; Westdeutscher Runfunk; Arte.

Welles, O. (Director) (1941). Citizen Kane [Motion Picture]. USA: Mercury productions; RKO radio pictures.

Welles, O. (Director) (1955). Mr. Arkadin [Motion Picture]. France; Spain; Suisse: Filmorsa; Cervantes films; Sevilla films; Mercury productions.

Wilder, B. (Director) (1950). Sunset Boulevard [Motion Picture]. USA: Paramount Pictures.

Zemeckis, R. (Director) (1985). Back to the Future [Motion Picture]. USA: Universal Pictures; Amblin Entertainment; U-Drive Productions.

Author contacts

Lluís Anyó – lluisas@blanquerna.url.edu