Laurie-Mei Ross Dionne (Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue), Fabienne Sacy (Université de Montréal) & Carl Therrien (Université de Montréal)

Abstract

Visual novels are known for their gameplay, which tends to be heavily focused on branching narratives, allowing players to experience many stories within the same world. We will explain how these games are contextualized in the Japanese market, and how their specific template has been adapted by other creators in order to tell their own unrepresented stories. This paper highlights how this can be a conduit for exploring various identities, such as heterosexual women, homosexual men, and broader queer identities that are not often represented in compassionate stories and environments. Furthermore, we will examine how sociocultural issues can feed into the themes and subjects of the games, yet still be presented with humor and an overall care for the characters, and, by extension, the player. This delicate balance will be showcased through analyses of the games Cupid Parasite, Coming Out On Top, and Hustle Cat.

1. Introduction

One criticism often lobbed against video games is the overrepresentation of heterosexual male protagonists and the small window of opportunity for other identities to take center stage. This was often paired with the issue of female representation tending to be synonymous with (hyper)sexualization and being secondary to their male counterpart (Kondrat, 2015; Lynch et al., 2016), as well as relying upon a hegemonic construction of (white) heteromasculinity (Burrill, 2008; Dietz, 1998; Fron et al., 2007; Kline et al., 2003). This would lead to a cloistering of the industry, heavily politicizing what would be allowed in the digital playground, keeping the supposed minority of players out of a male-centric domain (Fron et al., 2007). The representation of diversity is still a hurdle in the main-stream video game industry (Williams et al., 2009). Although there has been a steady increase of female characters (Lynch et al., 2016) and noticeable improvement with female character portrayals (Hess, 2021; Silvis, 2021), there is still a lot dissatisfaction among female players (Silvis, 2021). On the other hand, heteronormativity seems to remain the norm, but it should be noted that LGBTQ+ content has been part of game history from 1985, and many identities are becoming more visible, even in mainstream games (Shaw et al., 2019).

However, as gamers outside the hegemonic white hetero-male category have become more visible, and genres oriented toward other demographics are becoming more prevalent, “masculine gaming culture responds with discourses of threat, anxiety, and containment – the latter accomplished by the continued degradation of casual games as simple, insignificant, and reductive of hard-core aesthetics” (Soderman, 2017, p. 42).

This may be part of the reason why visual novels have been overlooked, even if they have been offering alternative representation, such as female protagonists in stories that are made with a female audience in mind (the otome genre), or through the depiction of queer experiences such as homosexuality or gender non-conforming identities. With the ever-expanding catalogue of games being compiled on fan-made databases, we want to shine a light on this genre often relegated to the sidelines and showcase a sample of the richness and diversity it has to offer.

This article argues that novel games are able to usher the gaming culture to a multitude of voices and, in doing so, allow for the exploration of new identities in a safe environment. We will establish how novel games position themselves amidst the corpus of interactive digital narratives through their structure, heavily focused on branching narratives and alternate timelines, and follow up with how players in this specific context may relate to their avatar. This, in turn, will allow us to explore the potential for creating a safe space for narrative exploration, even when confronted with representations of toxic or otherwise unbalanced relationships, through the presentation of the findings obtained through fieldwork with otome game players. Then, we will present three different cases recentering the experiences and representations of protagonists that fall outside of heteromasculine norms. We will argue that these games depict (and are the reflection of) several socio-cultural issues pertaining to the communities that they simultaneously represent and establish as their target audience. Through a close-reading approach within the scope of cultural and gender studies, we will begin by exploring a female-centric experience with an otome game, Cupid Parasite. Then, we will delve into games that are repurposing the Japanese novel game genre to cater to queer audiences, with Coming Out on Top and Hustle Cat.

2. Defining a genre and the importance of the cultural lens

The expression “visual novel” is gaining a lot of attention in contemporary gaming culture all over the world. It refers to a genre originating from Japan, however, as the Japanese director and writer Uchikoshi Kotaro mentions, the term “visual novel” does not really represent a genre in his country (Szczepaniak, 2014, p. 277). His games, such as Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors (Chunsoft, 2010), are known as adventure games in Japan. Ryukishi07, creator of Higurashi When They Cry (07th Expansion, 2002), reinforces this notion, as their game “would be somewhere in-between an action game and a novel. So [he] believe[s] that because [they have] this, let’s say, central position – at the center between all these different genres – depending on which elements are stressed [they] could become closer to action games, or closer to an actual novel” (Szczepaniak, 2014, p. 215). Novel games are understood as interactive books, able to steer the narrative into different paths to reflect the player’s choices, not unlike choose-your-own-adventure books.

Another important category, ren’ai-sim (literally translated as love simulation game) or dating-sim, are games centered around a dating system where the protagonist may find love with a predetermined pool of available lovers. Depending on the targeted audience, the term and established trope vary: bishoujo games are geared toward a heterosexual male audience, while otome games offer similar opportunities for female audiences, allowing them to romance male partners through a female protagonist (Taylor, 2007). Homosexual relationships are also clearly visible in Japan through the yaoi genre, whose content was largely produced at first by and for heterosexual women, but as Nagaike (2015) notes, homosexual (and even heterosexual) men who seek to escape heteropatriarchal normativity have now embraced this culture. The genre that appears to depict lesbian relationships and is known as yuri, on the other hand, is a bit different, as it does not have a core demographic in mind. This term encompasses any media that showcase intense emotional connection, and romantic or physical desire between women. The gameplay of ren’ai-sim games usually puts forward a system of parameters that the protagonist must raise, such as fitness and art in the case of Tokimeki Memorial Girl Side (Konami, 2002), in order to unlock potential dates and maintain their interest during the allotted in-game time. The games the case studies presented in this article were conducted upon undoubtedly operate on a dating system, but the absence of stats building, and time management is a strong argument to them closer to the novel genre. Thus, instead of viewing them as dating-sim games, we argue that they should be thought of as novel games with dating-sim elements. Even if novel games have expanded outside of Japan, we believe it is fair to restitute terms closer to the ones that are part of the established vocabulary, and that will be how we will refer to these games from here on out.

3. Embracing alternate realities

While the lower cost of production of novel games can be a contributing factor to their ever-expending catalogue, the format also means easier accessibility for creators to tell their stories. Hatoful Boyfriend (Mediatonic, 2015), the quirky novel game about romancing pigeons, was made singlehandedly by the mangaka Moa Hato. Others have been using the free game engine Ren’Py to bring their worlds to life. Such is the case with Katawa Shoujo (Four Leaf Studio, 2012) and its development team, which was the result of an online collaboration stemming from an interest in creating a narrative based on artwork by RAITA, a manga artist, depicting characters with disabilities.

“The theme of disability becomes central to the relationships that [the male protagonist] cultivates with each of the women but the game avoids a representation of disability that defines relationships. [For the developers and writers,] disability is stressed as an initial character trait which when combined with broader personalities, interests, experience, and the setting open onto much more complex identities and characterizations” (Champlin, 2014, p. 66).

The novel genre can cater to the needs of all kinds of communities and bring forward characters that cannot be reduced to a single attribute. It allows for the exploration of other realities, with a variety of tones and aesthetics. Smaller teams of developers means more control on the product they want to create, and on how they produce it. Their voices can be expressed more freely, allowing for a greater diversity of representations, not hindered by the mainstream industry, which may be less inclined to finance projects like these. While some games are self-funded, some developers will instead present their projects on crowdfunding platforms like Kickstarter and rely on the interest of the community for funding. Coming Out On Top (Obscurasoft, 2014), a game focused on gay dating, complemented with a heavy dose of pun-based humor, and Hustle Cat (Date Nighto, 2016), a dating game with a focus on accessibility and LGBTQ+ friendliness, are two of these successful, fully backed projects, with over 1,000 contributors each, largely surpassing their original stretch goals (Kickstarter, 2012; Kickstarter, 2015). This shows how the novel genre encourages creators to put their ideas to the test, and these projects do get people invested in these stories – more so in stories that embrace the reality of many who have been pushed back the fringes, replaced by a heterosexual male protagonist.

4. What if? How branching narratives have always been a powerful tool for player reflexivity

Interactive narratives have been discussed extensively in academic literature in the 1990s and beyond, fueled by the popularity of interactive fiction (IF) and, more broadly, hypertextual experiments. In Twisty Little Passages (2003), Nick Montfort highlights how the IF genre, made popular by Infocom and other studios, was seen unequivocally as games in the community, despite being text-based – the complicated puzzles they proposed were, after all, built on the age-old tradition of the text-based riddle (2003). For Montfort, parser-based IF offers world simulations, but some of these games might present this world in a way that mimics more simple branching narratives. The later chapter reveals that IF created a thriving community way beyond Infocom’s commercial prime time in the 1980s, with later experiments, such as Emily Short’s Galatea (Short, 2000), focusing more on conversation with simulated characters. Some of these works put less emphasis on puzzle-solving, yet “some interactors worked around by devising a challenge for themselves and attempting to find every possible final reply” (Montfort, 2003, p. 219).

“Interactive branching narrative” implies the possibility of choice and repercussions. We saw a renewed interest in the adventure game genre with the release of The Walking Dead Season 1 (Telltale Games, 2012) and cinematic experiences with the release of Heavy Rain (Quantic Dream, 2010). These titles often put forward the idea that every choice is meaningful and will deeply impact how the story unfolds, a “butterfly effect” in action. As appealing as it sounds, these games are still bound by a rather linear narrative thread, albeit with a different weaving each time that story is played. This is due to the fold-back structure they all share, where the player is given options, but all the different paths will lead to the same place as the branches will recombine. In other words, there is a core (or some story beats) that will always be experienced, but the choices made previously may slightly alter the scenes. Ryan (2006) establishes a distinction between what she calls a tree – a narrative structure where each choice results in a new branching path – and a flowchart – where choices will let the player stray from the main linear thread briefly, but quickly bring them back onto that main path, limiting the expected expansion of possibilities (2006, p. 104). Interactive fiction, in the case of flowcharts, creates space for modular elements to craft a player-based narrative, while allowing the developers to retain control on the overall story they desire to tell and to keep the production of each different segment manageable. That is not to say the player is robbed of meaningful choices, as to see how choices will influence the story, and even anticipate how events may play out around player decisions, is part of the fascination surrounding these games. The fact that these games often feature social situations and moral dilemmas as their central themes can also contribute to their attractiveness, making the choices and situations presented to the players feel meaningful.

As many have pointed out, player choices typically influence the avatar’s personality, behavior, and relationship with others. The avatar is meant to be both a conduit for expression and self-reflection (Bell et al., 2015; Zagal, 2011). Witnessing all the possible outcomes is a reason for replayability, and a source of excitement for players who desire to see what could have happened. However, trudging through the same overall story could deter some players. To sum it up employing Ryan’s concepts, pleasure can be derived from what is designated as an ontological approach to interactivity, where player choices do impact the world of the game, but also from a more exploratory experience, where the player is encouraged to figure out the “map” of all possible choices, gaining a deeper understanding of the game’s narrative options (2006, p. 108).

5. The structure of novel games and the appeal of exploration

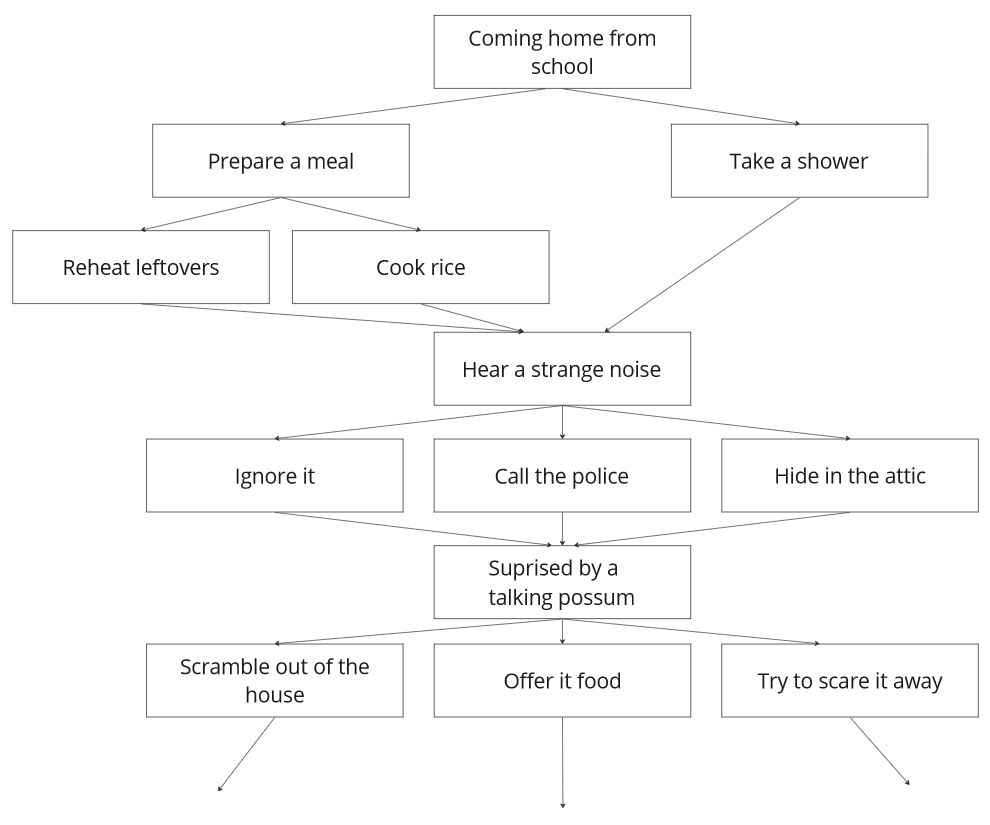

One of the key elements that sets apart many games within the novel genre is their use of a true branching structure featuring “major” branches, commonly referred to as “routes”, which vary so much that they can almost be considered entirely different world states. The game will initially present its protagonist and setting with a prologue, often referred as the “common route”. This may present itself as a fold-back structure, but many options are actual flags in disguise. By “flag”, we refer to the recognition that a moment where the player is faced with a narrative choice is a point to which they can later come back to experience a different outcome. In other words, as players map out the ways in which branching paths interconnect and separate, they might, for example, create a separate save file (metaphorically planting a flag) which they intend to return to at a later time. In this case, this will usually be paired with the possibility to branch out to a character’s specific route. The other choices available are still relevant, as they flesh out the world and the protagonist’s mindset or help shape their preferences. After the first key branching point, the game will split in different directions and explore facets of the world through the relationships with the featured cast of companions, as well as the main love interest associated with the route (Figure 1). The aforementioned novel games may be played differently each time, but a playthrough is still discrete – one can play, finish, and feel satisfied that the core experience has been achieved. Yet, numerous novel games reward players who seek all possible outcomes (by playing all available routes) with resolutions to an overarching plot. Those games tend to include “secret” or “true” endings which act as a resolution to the underlying mystery established, making it very hard for players to ignore the efforts put in place to encourage exploration. Even “bad endings”, often compared to the usual “game over” screen, are sometimes employed to learn more about the game’s overarching story, or even to reveal characters that will eventually appear in other routes – as a form of foreshadowing.

In other words, if replayability was an option before, here, it becomes an almost forced mechanic, and for some, the ideal way of playing. Most games even facilitate the exploration of branching narratives through the use of a quick save/load system and an auto-read setting whenever the text has already been viewed. That being said, this structure still provides meaningful individual stories for each route, as it offers a more thorough understanding of the cast of characters featured, and of how each of them fares in new situations. This often challenges them in their own perspective, identity, resolution, and ideals. The avatar, on the other hand, is more malleable, as the exploration of possible worlds give them opportunities to grow and actualize their different selves. This also applies to the player: as they journey with their avatar, they can react and reflect on the situations given, steering their virtual counterpart toward what they may believe would be best for them (both). The many-world structure allows for a safe exploration of identity within the same game, and routes that may present harmful contents that can still be worked around, as we will later see.

This narrative fragmentation is often presented with locked routes and options upon the first run, while the player is free to choose the order in which they experience the options available at the beginning. As we have underlined, the last route unlocked is often labeled in-game as the “true route”1 associated with the “true ending”, as they serve as the final piece of the puzzle that brings forth what was truly happening all along. Route selection is not always presented as an explicit choice. Option selection may underline a point system where the game will eventually force the player on a specific route depending on the obtained score. For exemple, in Hakuoki Demon of the Fleeting Blossom (Otomate & Design Factory, 2012), after being captured at the beginning of the game, our protagonist can choose to escape rather than try to explain her situation to her captors. Her attempt will be thwarted, but the following choice will determine who will gain affection points toward her: Okita (if she stays) or Hijitaka (if she tries to run). While it may be obvious that some choices are tied to specific characters, this mechanic could still be felt as a more intuitive way to determine which route to explore on the first playthrough, as a player who answers more instinctively would be steered toward a potential lover with whom they have a stronger affinity. We can see how novel games grant the player the ability to choose, not only during playable segments, but even what kind of path they want to explore. This is a good way to create player engagement: by allowing them to select which story they want to investigate first, they may be even more inclined to pursue the other routes in order to know what they contain.

6. Otome games in Japan: Catering to a female audience

We presented earlier how the inclusion of primary female characters is still facing an uphill battle. Thanks to the recent surge of popularity of otome games, many new female perspectives were brought to the centerstage in the West. Otome games have steadily been released since the successful introduction of Hakuoki: Demon of the Fleeting Blossom. Western studios have even begun to adapt the formula for their own target audiences, as it is the case with Beemoov and 1492 Studio, which are developing games for the French market (Andlauer, 2016; Denayrouse, 2019). The same phenomenon is also happening in the East with the growth of the Chinese (Liang, 2020) and Korean (Ganzon, 2019) otome markets.

Yet, these games have been part of the culture of games made for women by women in Japan since 1994, with the release of Angelique (Ruby Party, 1994). The game was created by a female team inside of Koei, wanting to craft a product dedicated to a female audience (Hasegawa, 2013; Kim, 2009). It should be noted that here, the term otome is also known to be part of the broader term of jyoseimuke gemu (literally translated as “games for women”). Therefore, they are not seen as a genre, but rather as a category of games, encompassing a variety of genres such as adventure, simulation and role-playing games, usually with an emphasis on a romance system and a tendency to simplify gameplay. However, many Western fans are most familiar with the otome novel type, and this is the one that we will refer to in this section.

The existence of otome games in Japan should also be presented as a positive example of female marketing strategies, as they were shown during the fieldwork portion of a study conducted on otome games (Ross Dionne, 2020) which specifically targeted two areas in Tokyo: Akihabara and the Otome Road of Ikebukuro. What became apparent was the different approaches when it came to displaying those games in video game stores. In Akihabara, renowned and framed as catering to (heterosexual) male fantasies, otome games were displayed with very noticeable markings, such as a color-coded section. This seemed to suggest the importance given to these games and their customers. Since female customers are not the usual target audience of these stores, creating a visibly delineated space for them could be a marketing tactic to make them feel welcome. This was contrasted with videogame stores in Ikebukuro, which scarcely used such tactics while still offering otome titles. We can therefore assume that by the very nature of their location on Otome Road, businesses did not need to make as much effort to encourage women to browse their establishments, as they were the prevalent and intended customers.

As mentioned in our introduction, female representation and even female audiences have often been relegated to the sidelines. Yet, the case of Japanese otome games and the marketing strategies employed for them show how women can be (and have been) considered a legitimate and primary group of consumers. This observation does not invalidate the former statement. Rather, it shows how we should still be mindful of individual trajectories, and not fall prey to ethnocentric (or, in the present situation, Western-centric) assumptions.

7. Player’s identity, the avatar, and the power of agency

Novel games often try to de-emphasize the physical representation of their protagonist. “Silent protagonist” is the name usually given to this typical avatar, which is hidden from sight via the use of a first-person point of view and not given a voice actor, even when other characters are voiced. Although they may make a brief appearance during the game’s CGs (short for Computer Graphic, full-screen pictures that are meant to reinforce and highlight a narrative or emotional event), in such instances, some protagonists are drawn with no eyes, or their face is partially obscured as a means to un-characterize them. Furthermore, the player can usually rename them – that is, if they even have a default name to begin with. Some recent games include the protagonist’s portrait during dialogues, but all games that do so, to our knowledge, also offer the option to hide them. This is thought to be a design decision meant to reinforce the player’s illusion to be their own character, answering and choosing as themselves.

Yet, we should not be too quick to conflate player identity and avatar identity. This strategy may function if the character is truly the empty shell they are depicted to be, but in novel games, we often have access to inner monologues, descriptions of reactions, and the emotional state of the protagonist. Through the analysis of otome game players’ experiences (Ross Dionne, 2020), it became apparent that the participants’ relationship with their avatar oscillated between two main paradigms. Most of them declared that they perceived themselves to be in a “silent spectatorship” situation, accompanying and guiding their avatar. There was distance between the two of them, as their avatar was a character with a distinct will. It was seen as a form of partnership. The rift between identities at play would be noticed when, for example, the player thought that the protagonist behaved illogically: it was no longer their choices, but the ones made by someone else. The other participants would describe their relationship with their avatar as a “virtual representation of the self”. While they also viewed their avatar as a full-fledged character, the agency experienced through the various choices they could make were enough to provide them with the feeling of being in the gameworld. Individual perception played a more important role in characterizing how players felt toward their avatar than the decisions of designers. For example, the same techniques to depersonalize and disembody the avatar could contribute to both relationship paradigms. In the first instance, as mentioned previously, the inner monologue and choices the avatar made would reinforce the notion that this was a character, and not a conduit for the player’s intention. Moreover, the presence of CG would be perceived as a reminder that it was truly someone “else” who experienced these adventures. On the other hand, those who felt embodied in the gameworld would argue that not seeing who they were fueled their feeling of identification. As for the CG, it did not pull them out of their state of belief. They even preferred to see their avatar for aesthetic reasons, arguing that a first-person GC would often be hard to understand and feel strange.

The individual interviews conducted during that study allowed for a more nuanced explanation and understanding of what this could mean for player agency and experience. The study showed that players could always feel their ability to establish limits in terms of what was acceptable for them when the topic of unhealthy relationships was presented. The reasons varied greatly, and the two paradigms of relationship were reflected in how this resolved. Some players would refuse to continue a route where the romantic interest was perceived as abusive, controlling, or dismissive toward the protagonist, such as Toma in Amnesia: Memories (Idea Factory & Design Factory, 2015), or Takeru Sasasuka in CollarxMalice (Otomate & Design Factory, 2017). Reasons for players to halt their progression in these routes could be that they anticipated that the game would legitimize this kind of relationship, and they refused to allow it, through their resistance. They wished to see their avatar in a positive and respectful relationship. For those on the silent spectatorship side, the choice was really an act of care for their character, as they wished for the avatar’s happiness. For those on the “virtual representation of the self” side, the sudden stop was instead linked to their own perception of what could be tolerated in a relationship, and they applied the same standards within the game world. In a more linear structure, this would mean the end of the game, but in a branching one, the players may still enjoy other possibilities. While it is true that the completion of all routes is needed to really understand the central plot and overall mystery, each route is still complete in itself and may be fulfilling in its own way, through the development of a relationship and the resulting character growth it presents.

Others on the “silent spectator” side of the spectrum would not be affected by the romantic interests’ attitudes, even when they displayed cruelty toward the avatar. Such players would not let these situations affect them; they knew it was a piece of fiction, and therefore did not feel that their own well-being was threatened. This could even be paired with a desire to know why these partners acted the way they did. As the players allocate a considerable amount of time to getting to know their fictional partner better, they may approach the game with the expectation of reaching a deeper level of social and emotional investment. The desire to seek the truth and pull the veil off the mystery would sustain their pursuit of any routes, no matter what kind of relationship was presented.

Another way to negotiate the dynamic at play was to let the route run its course, but select the options that would halt the relationship, and thus purposefully “try to fail”. This may lead to a “bad ending”, but it would be a meaningful outcome, as players are granted the privilege of the final decision regarding which ending was the most satisfying and real for them. Even if players experience every relationship, they get to choose their own canon ending, regardless of the in-game labels attributed to endings, (bad, good, great, true…), as the “player remembers both the fail state and the success state, and for the player, both states are plausible endings to the story. In other words, the player remembers the hypertext story, and not both instances of narrative as separate narratives” (Van der Geest, 2015, p. 21).

Yet, some players may even find appeal in the toxic dynamic presented. Diabolik Lovers ~Haunted Dark Bridal~ (Rejet, 2012) is a distortion of typical scenarios depicted in otome games, where the potential lovers are all sadistic vampires, finding pleasure in torturing and humiliating the protagonist. In this case, the exploration of taboo or dangerous situations can be part of the appeal; the audience can find it thrilling because it allows for a safe exploration of these elements, a phenomenon that has also been observed with horror fiction (Cosmos, 2018).

This small sample showcases how players may feel safe in interacting with fiction where a troubling relationship is depicted. The ability to play in a secure emotional environment is supported by the many-stories structure, no matter how the player is engaging with their avatar. That is also true for positive experiences. The following case studies of Cupid Parasite, Coming Out on Top, and Hustle Cat will show how novel games also provide an ideal background for self-exploration within a safe space, while presenting a variety of situations and emotions.

8. From agape to storge, love can express itself in different ways: a positive look on relationships and mutual growth

Cupid Parasite (Otomate & Idea Factory, 2021) examines the concept of love and relationships in an holistic manner, with a dash of fantasy and comedy, using the Greco-Roman mythos as a backdrop for its setting. The different potential lovers are associated with one of the six types of love, designated with Greek terminology, such as agape (dedicated love), eros (love of beauty) or pragma (practical love), and befittingly, the player’s avatar is none other than Cupid herself. After being scolded by her father, Mars, on the decline of lasting relationships and the impact it has on the marriage rates, Cupid sets out to prove him wrong, believing that humankind is wonderful and does not need their interference anymore. Taking the name Lynette Mirror, she elects to do her job in the mortal realm, with human skills, and rise as the top modern-day Cupid, a bridal advisor at Cupid Corp. There she faces her biggest challenge yet: finding the perfect match for the infamous Parasite 5, men unable to find love, that every advisor has given up on. But what if that perfect candidate is her?

Through a positive, sincere, and deeply caring protagonist, the game is centered on the idea of understanding each other and working together to make a relationship work. As their bridal advisor in the common route, Lynette often chastises the Parasites 5 and tries to show them how to better interact with women while still being true to themselves. In their respective routes, this comes off as character growth that plays off what was taught to them during their lessons with her. Similarly, as a workaholic dedicated to bringing others together, Lynette is our “cupid parasite”. She does not know what love is, but her time with the men will lead her to understand and experience it through their own unique take on the matter.

During the common route, the game offers a “love match” test to find which type of love would better suit the player, and this will affect the possible outcomes of each route. A perfect love match with high affection from the romantic partner will ensure the best ending. Anything else will result in a range going from bad endings to good ones. This is an interesting concept, as players are invited to answer as themselves. The test is comprised of 14 questions and will not lock the player upon a route. Instead, it shows with whom they would be the most compatible, as the test results display the silhouette of the corresponding Parasite. It also offers an unusual twist on the formula: in the case of an incompatible match, players cannot obtain a good ending. Not all couples are meant to be together. The game shows that it should not be something that feels forced, no matter how much understanding and empathy there is. Nevertheless, in the context of the routes’ description, we will assume the player and the corresponding lover have a matching type, to ensure access to all endings.

Amongst the five men that Lynette must help, one of them is a “lovelorn parasite”, Gil Lovecraft, who is still pining for his first love from two years ago. That first crush is none other than Lynette herself; and through their reunion at Cupid Corp, he is given another chance at love. He is the representation of the agape love type, the selfless love, putting others’ needs before his own. In his case, this manifests itself as him being overbearing, but his real issue lies in his inability to properly communicate, and in assuming rather than ascertaining the facts. This combination leads to him going the extra mile, sometimes in the wrong direction. For example, he becomes a freelance editor to dedicate his free time to Lynette, because he overhears her say that she wants “a lover to always be by her side”, while in truth, it was her friend Claris who said those words using a voice-changing app. During his route, Gil is confronted to the reality that his actions, while sincerely thought to be for the benefit of his partner, also come out as selfish and self-imposing, as the other party is not given a say in the matter. His personal journey is centered on communication and finding compromise, curbing his tendency to overdo things, and respecting his partner’s desires, while still doting on her. This doesn’t mean that he no longer goes overboard, as his route shows him traveling to the realm of the Gods to pursue Lynette. To prove that he is serious about his undying love for her, he fights Mars, using his self-made transfocar, Bumblepig, an obvious nod to the Transformer franchise.

Initially, Lynette remarks that Gil’s excess comes from the right place but is definitively exhausting to receive. She does not mince her word when reflecting upon his behavior, but as his advisor and friend, she wants to help him understand how his affection may be perceived by others, especially women, who might be frightened by his intense behavior. Yet, upon the realization of her own feelings for him, she comes to see those gestures as pure declarations of love. She embraces his caring nature, but also wants to reciprocate and support him in her own way.

Another member of the cast of men assigned to Lynette is the “obsessed parasite”, Raul Aconite, a Sillywood actor who will feature in his first romance film, but his lack of knowledge in that department leads him to join Cupid Corp. He fittingly is obsessed with mythology, especially the Greco-Roman sphere of myths, even if he is wildly wrong about many things, such as being convinced that Neptune is a woman (something that Lynette will eventually rectify with her knowledge as Cupid). His route is very comical and light, true to his love type. Raul is a ludus love type, who sees love as fun, preferring short-term relationships over a longer one with a single person. This manifests itself through his engagement in frequent casual sex, and while Lynette has a more reserved view on the matter, she does partake and find enjoyment in it. She is open-minded, trying to understand his belief that consensual sex is a fun way to engage with someone. The two eventually realize their feelings for each other and do perceive things differently once they are in love, but the game does not vilify sex or treat it as a taboo. Rather, it shows how a healthy casual relationship can eventually lead to something more, and how sexuality is part of life. In this route, both characters are challenged on their preconceptions and learn how to accept each other’s views.

While the game does not explicitly explain the reason behind the term “parasite”, it is implied that it is due to their extreme traits that deter any potential marriage candidate. Culturally, it can also be linked to the Japanese concept of “parasite singles”, referring to young adults in their twenties still living with their parents and being taken care of, effectively “leeching” off parental affection. These unmarried singles are often blamed for societal issues such as the declining birth-rate (Aihara, 2011; Tran, 2006), as marriage and childrearing is heavily correlated in Japan, with only 2-3% of childbirths registered outside of marriage (Aihara, 2011; Harvey, 2017; OCDE, 2018). It is no surprise then that all of the best endings for each character show them proposing to the protagonist.

Cupid Parasite does not make an apology of its characters and their flaws. Each of them comes to terms with their shortcomings, while still becoming their better selves and being true to their unique type of love. This is also true for Lynette. Through her genuine care for them, she also undergoes her own growth, as she learns to understand them better, as well as their unique way of expressing their care for others. With Gil, she can enjoy being pampered and caring toward him, and with Raul, she can explore her sexuality and how it relates to love. The exploration of different love types is a fine example of how a branching narrative can help shape the player-character and allow them to embrace different ways of being. This also presents these multiple ways of being as all equal and worthwhile. Nonetheless, it may also underline how the idea of the married couple remains normative in Japanese society.

9. “Your cooking sucks, your soufflé collapsed”: Exploring meaningful failures

As a novel game with dating sim elements, Coming Out On Top (henceforth COOT) is as straight as they come: it sticks to the common features we have highlighted in the first sections of this paper. In this section, we inspect how players can explore sexual identities in a safe context, and we expand our analysis to consider how navigating dead ends and even major failures can resonate with the experience of gay men, and more broadly with the reappropriation of failure as a cornerstone of contemporary queer studies (Halberstam, 2011). Like many Japanese novel games associated with the yaoi genre, COOT was created by a woman, Obscura, who expected to find an audience of (heterosexual) women, even if she did not set out to make a yaoi game herself (Kickstarter, 2012). However, as the author highlights, the most enthusiastic response came from the gay community: “They appreciated that I was making something different from existing yaoi games, that it was Western, that it was fairly realistic in terms of dialogue and characterization, and so forth” (Wright, 2013). As Poirier-Poulin notes, the humor is at the core of the game. Heavily intertwined with sex, it can be read as a form of transgression as it breaks with the usual taboo associated with homosexuality and sex (2022). Interestingly, the accumulation of puns, double entendres, and effective punch lines at the expense of the protagonist manages to bring us beyond comical distance and add up to generate sympathetic emotions, and even moments of deep empathetic projections that might hit awfully close to home for many players (gay or not). The game allows players to customize the level of body hair, the name of the protagonist, and – surprisingly – the name of his goldfish. We set out to find love in all the wrong places with a fully bearded, shaggy Mick Jones and his soaked buddy, Sleazy Pig.

COOT proposes a roaster of six potential lovers to seduce on the protagonists’ last year at Orlin University. Mick begins this decisive year by coming out to his good friends Penny and Ian. The school setting is quite prevalent in Japanese dating sims and its scandalous potential is fully exploited here: on his first night out, Mick inadvertently flirts with Mister Alex, who turns out to be his anatomy teacher. Instead of pursuing the main love interests, and in the spirit of keeping up with viable alternative routes, we will focus on two optional dates players can turn to in the in-game application Brofinder. This satirical version of Grindr doubles down on the sex-positive nature that characterizes some of the main romantic interests, yet in every case, players need to get interested in the various personalities in order to move forward and collect pornographic reward spectacles, which will be added to a main gallery for on-demand contemplation. This reward system stimulates replay value in many ways; the most competitive players will need to go through the branching structure multiple times to collect them all.

Some of the extra dates are designed in a way that maximizes the desire to perform and score in this ludic system, but even these extra “missions” emphasize the necessity to engage in meaningful dialogue. For instance, the date with Orlin county prosecutor Tommy leads to a kidnapping when our couple’s driver recognizes the man responsible for his imprisonment. Faced with murderous rage, at gunpoint, Mick tries to level with this character through the power of conversation and empathy. Lip service will not be enough to save the sexy couple from a literal dead end in the branching narrative. As an ultimate test, Mick must remember the antagonist’s name perfectly, and select it from three very similar variations. Choosing anything but “Darryl John Michael Wayne” finishes the date in a dramatic way.

This humorous quiz challenge highlights how novel games focus on listening and caring. This could also be said of Mick’s date with Oz and Pete, an adventurous couple met on Brofinder. Incidentally, early interactions with Oz on the app bring up communication issues right away, with awkward dirty talk attempts about fetishes, and the further realization that Mick was in fact discussing with Pete. Our future cuckolding heroes meet at a gay bar where further tensions arise: while they flaunt their communication skills as a key ingredient in their relationship, Oz and Pete appear to withhold some elements of their fantasies to each other, going so far as to belittle cuckolding in front of Mick. Interestingly, players will get one of the most complete repertoires of answers when finally asked how Mick feels about it (Figure 2), as if the designer wished to provide an honest canvas for players’ insertion at that very moment.

Exploring unproductive routes – seduction-wise – might still lead to some narrative gratification, or Steam achievements such as “cookolding” (obtained by selecting the dirty talk option quoted in the title of this section). This could also be said of the main narrative arc: if players fail to pursue a viable route with one of the main love interests, as we did, he will be directed to one of the boldest, destabilizing, and challenging game finales in the history of the medium. Videogames have been defined by Juul as the art of failure (2016); COOT seems to adopt this definition literally, proposing one of the most tragic endings we have seen, yet trying to bring some gratification and humor into the mix.

* Content warning* The following deals with very serious issues such as mental illness, psychosis, zoophilia, and homicidal thoughts.

Throughout the game, Mick gets a close-up of Sleazy Pig in its bowl while trying to decide how to spend the weekend. In the tragic final narrative branch, Mick starts to address his goldfish directly. As we previously said in the Player’s Identity section of the article, the player is always able to refuse a route, hereby able to negotiate what is acceptable for them without missing on the other stories the game has to offer. Some players, who may sense and fear the dark descent ahead, can easily reload to a previous safe moment in the story. Others might notice that this narrative branch is surprisingly fleshed out and decide to explore it all the way. Ian and Penny actually try to have an intervention with their friend about the player’s obsession with his pet. At this point, players can choose to isolate themselves completely, and even let Sleazy Pig “convince” them to kill the nosy friends. Thankfully, this goldfish conspiracy fails, and Penny flushes Sleazy Pig down the toilet. Friends try to get Mick to go out one last time to celebrate graduation. Should they decide to stay home, players can witness the ultimate failure in all its disturbing glory. Sleazy Pig crawls out of the pipes and proceeds to Mick’s room. The final embrace of a lonely gay man making love with his oversized goldfish is described with the same affectionate, caring phrasing seen throughout the game. This surreal image that completes the player’s gallery will not be easy to forget.

As Poirier-Poulin notes, building on Díaz, “game worlds such as COOT don’t simply reflect blind optimism, but can be read as sites of radical hope” (2022, p. 284). This could certainly apply to many queer novel games discussed in this paper and beyond. Yet by fleshing out such a provocative and dramatic finale, COOT echoes a previous generation of pop culture and LGBTQ+ literature in which traumatic events and dramatic endings seemed inescapable. This literary trope is referred to as “Bury Your Gays” and also answers to another name, the “Dead Lesbian Syndrome”, as female characters were predominantly the ones who suffered from it (Hulan, 2017). It refers to the fact that queer characters tend to suffer tragic fates (death being the most common instance) or see their relationships fall apart at a higher rate than heterosexual ones.

Through its humoristic and unapologetic lenses, COOT is able to muster laughter as a defense mechanism against the real trauma attached to the queer community. We are able to laugh at Mick and Sleazy pig’s primal embrace because we finally found our way into new story arcs, jumping out of the fishbowl, learning to breathe in toxic environments.

10. “We stick together through thick and thin, us cursed cats”: The queer experience of radical acceptance and unconditionnal care

Like COOT, Hustle Cat is a novel game aimed at a queer audience. While both employ a form of lighthearted humor, the resulting experiences differ in quite a few ways: where the former’s approach to every topic is unapologetic, from gay sex to failure and the underlying trauma present in the queer community, the latter represents a different kind of hope, one centered not only on inviting the player to care for its non-player characters, but also on the player letting themselves be cared for by the game.

Hustle Cat centers on player-character Avery, whose appearance and pronouns are chosen by the player (Figure 3)2, though they will always have their signature purple hair and yellow shirt – two of the four colors of the non-binary pride flag. First thrilled to be hired to work at a charming cat café, they soon realize with horror that anyone who works at said café is affected by a spell that turns them into a cat as soon as they leave the premises. Between everyday tasks and the wooing of attractive coworkers, Avery has to figure out what exactly caused the spell – and what things the café’s owner, the elusive Graves, seems to be hiding, as his route is the key to unraveling the mystery. The emphasis placed on the player-character, Avery, sets Hustle Cat apart from dating simulators that present heterosexual dynamics, which, as we have established, tend to employ tactics to make their main characters blank slates (although the previous analysis of Cupid Parasite and its player-character Lynette demonstrates that some games go against this trend). Avery’s name is not customizable, unlike the names of many visual novels’ main characters. However, what can be changed is their appearance, and the choice is important, as their portrait is often visible during the game, and they are incorporated in many of the game’s CGs. This could be seen as a manifestation of many queer identities’ desires for experiences that allow them to express their true, authentic selves: they get to choose Avery’s appearance and pronouns, seeing these choices constantly brought forth and affirmed by the game, and yet are free to date any character they fancy, regardless of their gender identity. Queer players are thus able to experience the game in a way that aligns with their own identity. Moreover, the game allows players to form romantic relationships with every member of the available dating pool, no matter which pronouns and appearances are chosen. The potential lovers are all attracted to Avery. In other words, rather than placing the players in a position where they need to align themselves with their desired romantic partner, every version of Avery is unconditionally accepted and welcomed.

It is also impossible to experience the failure typically associated with the dating simulator genre: the way players answer the text-based choices presented in the first part of the game only serves to determine which route they will end up on. In other words, romance is guaranteed – the only variable is who will be romanced. While a few specific choices will lead to bad endings (and thus, to a game over screen), we argue that these “failures” are specifically not associated with romantic relationships. It is thus impossible to experience rejection from the love interest, and that is another form of care that the game offers its players.

Similarly to Cupid Parasite, Hustle Cat uses the different members of the cast that can be romanced as a way to develop different sides of its player-character. While Avery’s main character traits remain unchanged no matter the path – they are always caring and sincere, and often too stubborn for their own good – the relationship dynamics at play often have them taking on a different role. For example, during the silent and straightforward chef Mason’s route, Avery is often depicted as blushing, intimidated by her unpredictable manners and unreadable expressions. And yet, Avery is the one who makes the timid and discreet Hayes blush in his own route. The different cast members all help them gain confidence in their own capacity – and in exchange, the player-character often forces them to confront situations that make them uncomfortable and resolve past trauma.

Queer visual novels such as Butterfly Soup (Lei, 2017) or //TODO: today (Boys Laugh +, 2018) tend to place a greater emphasis on platonic relationships, especially the feelings of belonging that a group of friends, coworkers or classmates might offer. This can be seen as a reflection of the queer experience of finding a chosen family (Weston, 1991), and it is a big part of Avery’s journey, and thus, indirectly, the players’. In Hustle Cat, while the endings of the different character routes are undoubtedly marked first and foremost by the success of the romantic relationship, they also emphasize how the coworkers have come to see each other as close friends. When Avery becomes the key to defending the café from an exterior menace, every character plays their part in protecting them, affirming that Avery has become a part of the group. In a world where queer people are still too often denied the experience of being accepted and loved by a group of friends, this is an invitation to leave behind the potential hardships in one’s life to take a break and experience pure, untainted happiness. Hustle Cat, hence, represents a form of comfort for the queer audience. In exchange, the player is invited to care for this cast of characters, to appreciate their unique personalities and, potentially, to attempt to date them in a subsequent playthrough, even if it is simply to get to know them better.

This motivation is almost guaranteed to be the drive that will lead players to Graves’ (the café’s owner) route, the secret ending of the game that can only be attained once every other non-player character’s route has been completed. Having been in a position to care for every employee in the café, players are able to empathize with the attachment that Graves feels for them, which finally allows them to get close to him. It soon becomes obvious that Graves tries to face his problems alone: the game’s antagonist, Nacht, who attacks the café at the end of every route in the game, is actually Graves’ on and off lover, and their relationship is a toxic one. Avery’s stubbornness forces Graves to accept his employees’ help, and everyone plays their part in finally vanquishing Nacht, allowing Graves to break free from a bond that holds him back. As Avery draws Graves in for a kiss, the game truly ends on an acknowledgment that while the future is never guaranteed – which can be once again interpreted as a nod to the shared trauma present in the queer community – the present is what matters most, and it is a happy one:

Avery [inner monologue]: I don’t know what’s going to happen from now on.

I don’t know how this is gonna work. I have Graves here with me.

That’s enough for now.

Thus, like COOT, Hustle Cat adapts the novel game mechanics to queer sensibilities. Kretzschmar and Salter (2020) underline that tension often remains in games that attempt such an endeavor. Quoting Monster Prom’s (Beautiful Glitch, 2018) developer, they argue that the very mechanics of the genre encourage an over-simplification of the characters that one can date, reducing them down to a series of traits. It remains that in the case of Hustle Cat, the attempt at creating a queer novel game with dating elements is in many ways successful, not only because of its affirmation of the player’s identity (through its player-character and the establishment of a feeling of belonging to a group), but also thanks to the insistence on caring for the player, who in turn cares for the non-player characters before their eyes.

11. Conclusions

Through their branching narrative format, novel games allow for more flexibility for authors to steer the characters’ growth in different directions, while still providing fragments of worldbuilding to assemble. This also provides a perfect setting for exploration that does not shy away from death or tragedy, allowing players to acquire more perspective on the unfolding narrative, as well as empathy for its characters. Nonetheless, we have shown how players are still capable of exerting their own agency, be it through how they approach the game (often in a completionist mindset) or by the establishment of their own boundaries regarding the storylines.

Novel games are a fertile playground to present stories centered on issues and experiences set apart from hypermasculine and male-oriented designs, which have been dominant in the gaming industry. In allowing players to experience other viable identities, as well as featuring choices that can at times be more challenging, novel games open up discussions and provide spaces for understanding. This is exemplified in the games that we presented, each proposing its own take on the matter. In Cupid Parasite, the foundation of a healthy relationship is built upon mutual growth – understanding and respecting each other, but also being able to recognize our flaws to become a better partner. Coming Out On Top allows us to explore different facets of our sexuality, and experience scenarios that are far from shaming us for doing so. The diverse potential companions are also treated equally, with the same respect, as we engage with them, paying attention to their stories and desires the same way our friends, Penny and Ian, care for us and are concerned with our well-being. Lastly, Hustle Cat expresses those spaces of exploration and understanding in the freedom of representation the game offers us, and in the overtly positive message that permeates the narrative: in togetherness we find solace, happiness, and a place where we belong, no matter who we are.

Novel games and their emphasis on the exploration of narratives may be the ideal place for reflection, and to resonate within players who may share a sameness of plight with protagonists that are more akin to themselves. Still, among gamers who are not heterosexual and male, there is a need for stories that are both mature and joyful – happy endings that embrace the multi-faceted aspect of interpersonal relationship, while still choosing to put forth hope that genuine care for another can overcome life’s trials. We believe that romantic novel games have the potential to fulfill the need for games that cater to a variety of audiences, and to do so in a way that shows gentleness toward players of many gender identities and backgrounds, with a lot of humor to facilitate discussions on topics that are still wrought with socio-cultural issues.

In sum, players are invited to care more for personal or collective hardship through the discovery of possibilities which, when compiled, provide a great deal of depth and complexity to the experience. And yet, this exploration is offered in a safe space that ultimately lets players renegotiate how far they wish to go, how much they want to see, and in what conditions they wish to experience these branching narratives.

Fundings. The research reported in this publication have been supported in part by funding from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada.

End notes

1. The “true route” is equated with the canonical ending of the over-arching story, as it is the one usually chosen when the videogame is part of a transmedial franchise with a non-linear medium.

2. Avery can either go by “he/him”, “she/her” or “they/them”, and the player can choose between six different portraits for their appearance. In the context of this article, we will use “they/them” to refer to Avery.

References

07th Expansion. (2002). Higurashi When They Cry. 07th Expansion.

Aihara, M. (2011). Mariage “en plus”: Particularité du mariage au Japon et conceptualisation de la maternité [Doctoral dissertation]. Université Toulouse le Mirail – Toulouse II.

Andlauer, L. (2016, June). Profils et avatars, identités au sein d’une communauté issue d’un jeu pour adolescentes. Médias Numériques et Communication Électronique. https://hal.archives-ouvertes.fr/hal-01373614

Bell, K., Taylor, N., & Kampe, C. (2015). Of Headshots and Hugs: Challenging Hypermasculinity through The Walking Dead Play. Ada New Media, 7. https://adanewmedia.org/2015/04/issue7-bellkampetaylor/

Burrill, D. A. (2008). Die tryin’: Videogames, masculinity, culture. Peter Lang.

Cosmos, A. M. (2018). Sadistic Lovers: Exploring Taboos in Otome Game. In H. McDonald (Ed.), Digital love: Romance and sexuality in games (pp. 245–252). Taylor & Francis.

Date Nighto. (2016). Hustle Cat. Date Nighto.

Denayrouse, C. (2019, February 10). Un amoureux virtuel dans votre smartphone. Tribune de Genève. https://www.tdg.ch/high-tech/jeux/amoureux-virtuel-smartphone/story/25915912

Dietz, T. L. (1998). An Examination of Violence and Gender Role Portrayals in Video Games: Implications for Gender Socialization and Aggressive Behavior. Sex Roles, 38(516), 425–442. https://doi.org/10.1023/A:1018709905920

Four Leaf Studio. (2012). Katawara Shoujo. Four Leaf Studio.

Fron, J., Fullerton, T., Morie, J. F., & Pearce, C. (2007). The Hegemony of Play. Proceedings of DiGRA, 4, 1–10. http://www.digra.org/wp-content/uploads/digital-library/07312.31224.pdf

Ganzon, S. C. (2019). Investing Time for Your In-Game Boyfriends and BFFs: Time as Commodity and the Simulation of Emotional Labor in Mystic Messenger. Games and Culture, 14(2), 139–153. https://doi.org/10.1177/1555412018793068

Halberstam, J. (2011). The Queer Art of Failure. Duke University Press.

Harvey, V. (2017). Les freins au désir d’enfant au Japon (note de recherche). Anthropologie et Sociétés, 41(2), 97–119. https://doi.org/10.7202/1042316ar

Hasegawa, K. (2013). Falling in Love with History: Japanese Girls’ Otome Sexuality and Queering Historical Imagination. In M. Kapell & A. B. R. Elliott (Eds.), Playing with the past: Digital games and the simulation of history (pp. 135–150). Bloomsbury Academic.

Hess, E. (2021). Les nouvelles représentations des minorités dans les Jeux vidéos: Enjeux et significations. ALTERNATIVE FRANCOPHONE, 2(8), 65–82. https://doi.org/10.29173/af29412

Hulan, H. (2017). Bury Your Gays: History, Usage, and Context. McNair Scholars Journal, 21(1), 17–27.

Juul, J. (2016). The Art of Failure. MIT Press.

Kickstarter. (2012). Coming Out On Top – A Gay Dating Sim Video Game. Kickstarter. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/obscurasoft/coming-out-on-top-a-gay-dating-sim-video-game

Kickstarter. (2015). Hustle Cat: A Visual Novel about a Magical Cat Cafe. Kickstarter. https://www.kickstarter.com/projects/datenighto/hustle-cat-a-visual-novel-about-a-magical-cat-cafe

Kim, H. (2009). Women’s Games in Japan: Gendered Identity and Narrative Construction. Theory Culture & Society, 26(2–3), 165–188. https://doi.org/10.1177/0263276409103132

Kline, S., Dyer-Witheford, N., & De Peuter, G. (2003). Digital Play: The interaction of Technology, Culture, and Marketing. McGill-Queen’s University Press.

Kondrat, X. (2015). Gender and video games: How is female gender generally represented in various genres of video games? Journal of Comparative Research in Anthropology and Sociology, 6(1), 171–193.

Kretzschmar, M., & Salter, A. (2020). Party Ghosts and Queer Teen Wolves: Monster Prom and Resisting Heteronormativity in Dating Simulators. International Conference on the Foundations of Digital Games, 1–8. https://doi.org/10.1145/3402942.3402975

Liang, M. (2020, May 3). Love and Producer: Otome games history and future in the East Asia – Global Media Technologies and Cultures Lab. http://globalmedia.mit.edu/2020/05/03/love-and-producer-otome-games-history-and-future-in-the-east-asia/

Lynch, T., Tompkins, J., van Driel, I. I., & Fritz, N. (2016). Sexy, Strong, and Secondary: A Content Analysis of Female Characters in Video Games across 31 Years. Journal of Communication, 66(4), 564–584. https://doi.org/10.1111/jcom.12237

Montfort, N. (2003). Twisty Little Passages: An approach to interactive fiction. MIT Press.

Nagaike, K. (2015). Do Heterosexual Men Dream of Homosexual Men?: BL Fudanshi and Discourse on Male Feminization. In Boys Love Manga and Beyond. University Press of Mississippi. https://doi.org/10.14325/mississippi/9781628461190.003.0010

OCDE. (2018). Shared births outside of marriage. OCDE Family Database. http://www.oecd.org/els/family/database.htm

Poirier-Poulin, S. (2022). “Mark Matthews Stars in ‘Anatomy is Hard!’ A Struggling Student Tries to Make the Grade with His Professor”: Sexual Humour and Queer Space in Coming Out on Top. In K. Bonello Rutter Giappone, T. Z. Majkowski, & J. Švelch (Eds.), Video Games and Comedy (pp. 271–288). Springer International Publishing. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-88338-6_14

Ross Dionne, L.-M. (2020). Réception et interprétation du couple dans les jeux otome: Une approche anthropologique d’un corpus vidéoludique japonais [Mémoire de maîtrise]. Université de Montréal.

Ruby Party. (1994). Angelique. Koei.

Ryan, M.-L. (2006). Avatars of Story (Vol. 17). University of Minnesota Press.

Shaw, A., Lauteria, E. W., Yang, H., Persaud, C. J., & Cole, A. M. (2019). Counting Queerness in Games: Trends in LGBTQ Digital Game Representation, 1985‒2005. 26.

Silvis, J. (2021). Sorry, Mario, but Our Better Representations of Women are in Another Video Game: A Qualitative Study on Women’s Perspective of Women Video Game Characters [Master’s Thesis]. Auburn.

Soderman, B. (2017). No time to dream: Killing time, casual games, and gender. In J. Malkowski & T. M. Russworm (Eds.), Gaming representation: Race, gender, and sexuality in video games (pp. 38–56). Indiana University Press.

Szczepaniak, J. (2014). The Untold History of Japanese Game Developers. SMG Szczepaniak.

Taylor, E. (2007). Dating-Simulation Games: Leisure and Gaming of Japanese Youth Culture. Southeast Review of Asian Studies, 29, 129–208.

Tran, M. (2006). Unable or Unwilling to Leave the Nest? An Analysis and Evaluation of Japanese Parasite Single Theories. Electronic Journal of Contemporary Japanese Studies, 2006.

Van der Geest, D. (2015). The role of Visual Novels as a Narrative Medium [Master’s Thesis]. University of Leiden.

Voltage. (2019). Enchanted in the Moonlight –Miyabi, Kyoga & Samon. Voltage.

Weston, K. (1991). Families We Choose: Lesbians, Gays, Kinship. Columbia University Press.

Williams, D., Martins, N., Consalvo, M., & Ivory, J. D. (2009). The virtual census: Representations of gender, race and age in video games. New Media & Society, 11(5), 815–834. https://doi.org/10.1177/1461444809105354

Wright, S. (2013, October 1). Obscura on her gay dating sim, Coming Out On Top. Stevivor. https://stevivor.com/features/interviews/obscura-gay-dating-sim-coming-top/

Zagal, J. P. (2011). Heavy Rain – How I Learned to Trust the Designer. Well Played 3.0 Video Games, Value and Meaning, 55–65.

Ludography

999: Nine Hours, Nine Persons, Nine Doors, Chunsoft, Japan, 2010.

Amnesia: Memories, Idea Factory & Design Factory, Japan, 2015.

Butterfly Soup, Brianna Lei, United States, 2017.

Collar x Malice, Otomate & Design Factory, Japan, 2017.

Coming Out On Top, Obscurasoft, United States, 2014.

Cupid Parasite, Otomate & Idea Factory, Japan, 2021.

Diabolik Lovers Haunted Dark Bridal, Rejet, Japan, 2012.

Galatea, Emily Short, United States, 2000.

Hatoful Boyfriend, Mediatonic, United Kingdom, 2015.

Hakuoki: Demon of the Fleeting Blossom, Otomate & Design Factory, Japan, 2012.

Heavy Rain, Quantic Dream, France, 2010.

Higurashi When They Cry, 07th Expansion, Japan, 2002.

Hustle Cat, Date Nighto, United States, 2016.

Katawa Shoujo, Four Leaf Studios, International, 2012.

Monster Prom, Beautiful Glitch, Spain, 2018.

The Walking Dead—Season 1, Telltale Games, United States, 2012.

Tokimeki Memorial Girl’s Side, Konami, Japan, 2002.

//TODO: today, Boys Laugh +, Germany, 2018.

Authors’ Info:

Laurie-Mei Ross Dionne

Université du Québec en Abitibi-Témiscamingue

Fabienne Sacy

Université de Montréal

Carl Therrien

Université de Montréal

This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial 4.0 International License.